It was early in 1969, and William Morris had a language to fix. On his desk, at 72 West 45th street in New York, was a stack of ballots, letters and interview notes from 104 of America's most important users-of-words. A writer for the New Yorker had written to campaign against the use of "senior citizen." The editor of Harper's magazine was lobbying for the use of "escalate" as a verb. Isaac Asimov had emphatically expressed his deep hatred of "finalize"; David Oglivy, the father of modern advertising, said of "hopefully": "If your dictionary could kill this horror, and do nothing else, it would be worth publishing."

These were the results of the first American Heritage Dictionary's Usage Panel, which has assembled most years since to decide which words belong in the English language, and which don't.

Today, even more so than in 1969, endeavors like this are mostly formalities--opportunities for a small group of people to comment on, rather than change, the tides of language. The only usage panel that matters today is open-admission: email, Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr. It’s very good at anointing new words to talk about new ideas. It’s bad at finding words to talk about itself.

One of the more contentious candidates in 1969 is a word we take for granted today: contact. The verb, not the noun, which has been in common usage since the 1600s. In the 1800s, people started using it as a verb, meaning "to bring or place in contact," which didn't seem to bother anyone. But by the ‘60s, people had started saying the word to mean "to communicate with," as in "contact me." The Panel could not abide this: It was voted down, 66 percent to 34 percent.

"Getting in contact" eventually made the cut in 1988, but by then it was too late: This noun had been verbed. Says the 1996 edition of the American Heritage Book of English Usage:

[The vagueness of "contact"] is a virtue in an age in which forms of communication have proliferated. The sentence 'we will contact you when the part comes in" allows for a variety of possible ways to communicate: by mail, telephone, computer or fax.'

What the panel couldn't have known was that "contact" may have been one of our last hopes for a sane way to talk about communication. Today we don't so much get in contact as we email (is that even a word?) text (a noun), message (barely a verb), Tweet (a brand) or Facebook (an admission of defeat). The only seemingly perfect electronic communication verb still in use--and, it’s worth noting, a verb before it was a noun--is "to call," but who even does that anymore?

***

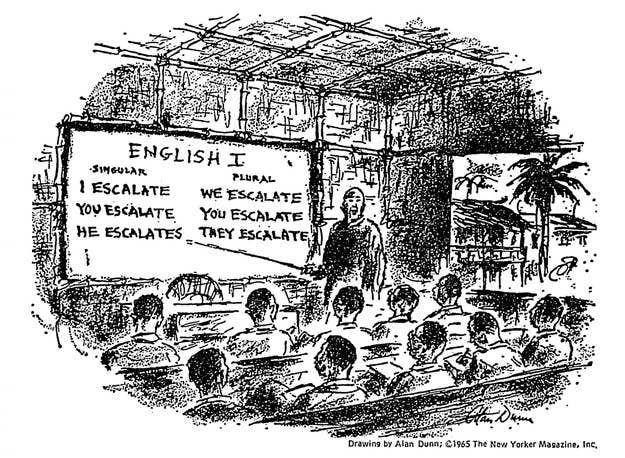

Nouns that have been "verbed" are known to linguists as denominal verbs, and they're everywhere: repurpose; boycott; boss; deplane; blanket; skin; label; juice; water; bribe; arm; book; bottle, can, package; author; blanket. You could list (there's one!) these for miles.

Eve Clark is the linguist who wrote the rulebook for verbing with Herbert Clark in 1979. According to their "Innovative Denominal Verb Convention," the most important thing is that people understand what you mean. In standard English, that means your verb-noun should be connected with a well-known action, like text to texting. With your friends, it can be an inside joke, or a person's name. ("Jesus, he really Wagnered it at the bar the other night, etc.")

Verbing is what linguists like to call an "innovation." That is, it's a way for new words to be created. "This is a very productive category in English," Clark, who is now a professor of Linguistics at Stanford, told me. She emphasized that it's been going on for very long time, and that it's a "a standard part of English." And it is! Just try to have a conversation without using these mutant nouns. No, better: Try to have a conversation about technology.

Of course I would feel dumb telling a friend who just tweeted at me that I "received your message," or a family member who liked my Facebook photo that I "have seen your feedback." But when I talk about tweeting and Facebooking, I do it self-consciously. I open my eyes a little wider. Maybe I smirk a little. I need you to know that I know just how silly I sound, and I'm guessing it does as lot more harm than good.

***

Two years ago The Awl circulated a memo from the New York Times standards editor, banning the word "tweet:"

Except for special effect, we try to avoid colloquialisms, neologisms and jargon. And "tweet" – as a noun or a verb, referring to messages on Twitter – is all three. Yet it has appeared 18 times in articles in the past month, in a range of sections."

He went on to worry that he didn't want the paper to seem "paleolithic"--which, ha? The Times, especially if it wants to have anything resembling up-to-date tech coverage, needs to allow "tweet" (and they still do). He did propose an interesting alternative:

[L]et's look for deft, English alternatives: use Twitter, post to or on Twitter, write on Twitter, a Twitter message, a Twitter update. Or, once you've established that Twitter is the medium, simply use "say" or "write."

The Times is worried about two things: That the paper will alienate readers, present and future, with weird neologisms; and that there's something fundamentally awkward about these noun-verbs, especially when they're derived from brands. It feels like there ought to be a better way to do this.

Like, maybe there's a more modern equivalent to "call". Its meaning comes from an action performed between people, not a specific technology. The phone may have taken a majority stake in this word, but it doesn't fully own it. I thought "call" might be more elegant, being that it's equally at home as a verb in, say, one of Shakespeare's plays as in the ad materials for a cellphone. From Macbeth: "Hark! I am call'd; my little spirit, see/ Sits in a foggy cloud, and stays for me, and so on." (Also from Macbeth: "Call 'em; let me see 'em." But you get the point.)

In any case, it feels like one of the good verbs, even better than "contact." Clark wouldn't have it.

"Do you think "call" is more elegant because you encounter it in 19th century novels?" Well, probably. No: Definitely. The only associations I make with "messaging" are with management consulting and politics, which poisons them a little. So maybe I've "eleganted" the word a little bit, and maybe that's not fair.

I asked Clark how we'll talk about communication in 10 or 15 years--long enough that we can't coherently talk about what Facebooking and tweeting will mean, or if those services and their companies will even exist. She's certain we'll deal with plenty more verbing; it's how English works. Maybe we'll all be Pathing one another. Maybe all of our interactions will fall under a dozen new verbs from the Farmville universe.

There is still hope, she says, for simplicity. Clark is betting on a reliable horse: "My guess is that most communication that will involve sending something to someone's address over the internet is probably going to end up with the term 'email.'"

I'll place a reluctant bet with "message." "Emailing" will stick around for a while, but it can't do anything messaging can't, and it's already beginning to sound a little bit antiquated. Texting is already halfway there. Public posts may just become messages to a person or a group. Social networks are different enough from one another now, but maybe not forever--then we can stop parroting their brands, or at least broaden the use of one. It's not impossible, for example, that tweeting could become the new xeroxing. Clark thinks it's at least a better candidate than "to Facebook,"; given its more narrow definition: short messages, sent to a large group.

Whatever we end up with, I'm sure the panel will come around eventually. They won"t really have a choice. And anyway, it's sort of up to you--if you have any good ideas, just email them to the comments, or sext them to my email, and maybe I'll blog them to this website.