A middle-aged market researcher is sitting in a trendily run-down loft in downtown New York City, surrounded by teens. "Tell me some of the things that are really hot right now, that are really big right now," he says to them. They have been paid a small sum to come to this event. "Popular, trends, things that you sort of see everywhere. What's, like, going on. What's hot right now? Just shout 'em out." The teens are silent.

And so opens the painful first scene of the 2001 Frontline episode "Merchants of Cool." The documentary explores, among other things, Viacom's legendary "ethnographic studies" of teenagers, designed to help MTV regain its cachet with young people.

In retrospect, the entire effort sounds almost like a joke — the concept of market research taken to its embarrassing conclusion, into teens' bedrooms in small-town New Jersey, where men with VP titles grill 16-year-olds about their sex lives. But there's evidence that it worked. And now there are signs that an abstract obsession with teens is manifesting in a new place: the tech industry.

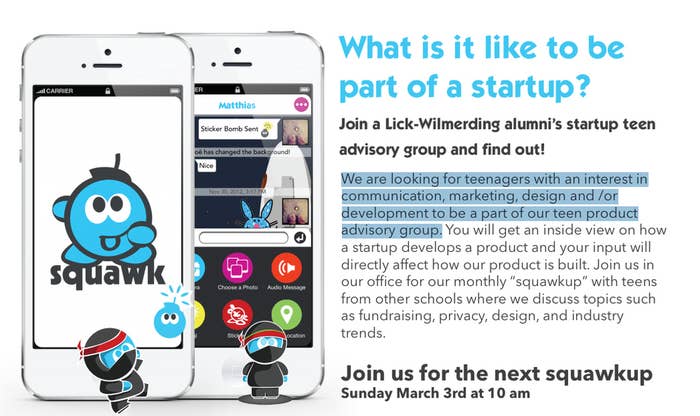

Squawk, a frustrating and compelling new messaging app, is targeted directly at teenagers. Its design is loud and messy, it has a temporary messaging feature, and it includes a quick-and-dirty meme generator. It was also designed with the help of a teen focus group. "We are looking for teenagers with an interest in communication, marketing, design and/or development to be a part of our teen product advisory group," the company said in a flyer posted earlier this year.

Squawk's Chloë Bregman, the 31-year-old who organized the group, said it took "several months" to get it together.

"They have more smartphones than anyone else," she says of teens. "They text message more than anyone else." The point, along with providing a mentorship program for young people, was to find out "how the youngest generation connects" and "how we see people connecting more in the future."

Squawk wasn't the first to try this. In February, Vine investor Adam Ludwin launched Albumatic, a photo-sharing app. He, too, focus-grouped teenagers: "Some of [the testers] are our nieces and nephews," he told BuzzFeed, "others are friends of those family members, and a handful are actually the actors we cast in our launch video."

Among the lessons he took from the teenagers: "Of the first seven we onboarded, two of them didn't have Facebook. When I asked them why, they responded that they were bored with it." Bregman's notes were similar. Her focus group also informed the app's deletion and archiving features, though she says it's important to take the gathered advice with a grain of salt and to make sure it works in practice. "What people say and what people do is very different," she says. The teens didn't really want a full deletion feature, it turned out, but an archiving option.

Whether or not the app will be a success remains to be seen; Squawk got a lot of attention on tech sites this week, most of it positive. Albumatic, which got even more attention when it launched, has struggled to amass a user base.

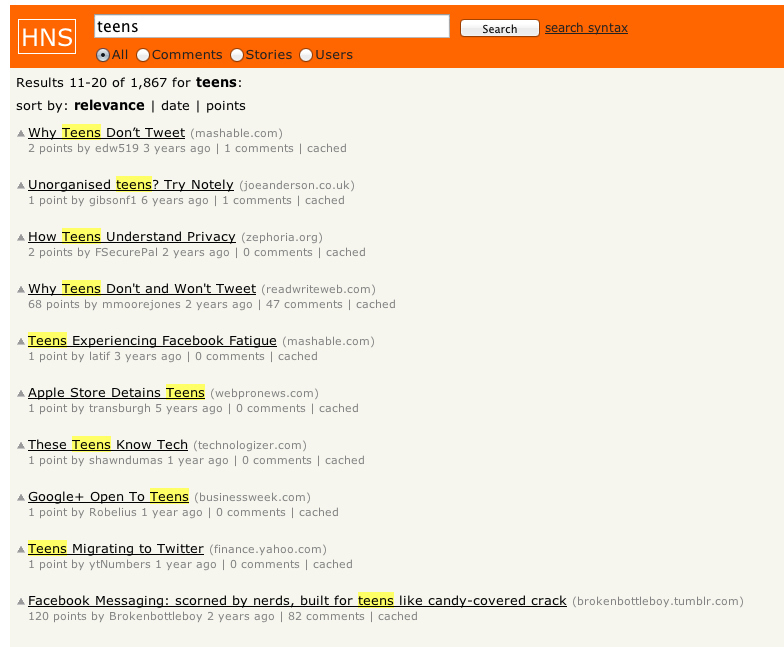

But the idea of the teen start-up adviser — the young user as an oracle — is here to stay. Post Snapchat, the tech industry (and tech media) is increasingly obsessed with the activities of the young and inscrutable. A search for "teens" on start-up watering hole Hacker News turns up 1,867 results. Most point to stories that purport to offer some insight — any insight! — into the teen mind, many of which were widely shared. The tech world is obsessed with teens. You might say it has a teen problem.

For start-ups, this results in using teens to figure out the next big thing. For the larger internet companies, it's less about predicting the future than buying into the constantly emerging teen market, again and again, and then figuring out how to sell ads against it.

Understanding this obsession will help to illuminate a lot of what's happened in social media over the last year. For instance: Vine and Instagram weren't just new ways to grow Twitter and Facebook, but to grow them downward, into colleges and high schools and middle schools; to ensure that the MTVs of the 2010s don't lose touch with their most valuable demographics.

Update: The finance world is getting in on this, too. Hours after this post went up, BTIG Research's Richard Greenfield, a respected analyst, sent out a report to his subscribers: "Watch the Teenage Cast of IMO Discuss Facebook and its Future."

IMO is a teen internet talk show. Greenfield advises subscribers and clients to read the comments "as YouTubers chime in from all around the world with their reactions to the IMO discussion," and says the video "highlights the challenge Facebook has maintaining engagement in a rapidly evolving media/technology/communications world."

Here it is:

Consider what this means: finance professionals around the world tuning into the 277th episode of an online-only teen girl talk show to learn about the future of Facebook. Then, consider that it kind of makes sense.