If there exists a trick to get your app to the top of the App Store charts, it's this: Make photos look better. For years, this meant simple contrast and color adjustment, or advanced camera settings, none of which were supported in iOS. By the time the iPhone's built-in apps supported simple photo editing, it was Hipstamatic and eventually Instagram, the de facto reality enhancer for smartphones.

Instagram's rise marked an important shift, from photo fixing and restoration to full-on photo enhancement. Instagram filters don't just improve a deficient smartphone camera, or make the photos look like they were taken with a nicer camera and lens — they create photos that are, at least to some viewers, better than reality. Colors are more vivid, contrasts sharper. You could call it powerful and exciting; you could call it cheating. The same could be said of the new generation of photo manipulation apps — let's call them the plastic surgery apps.

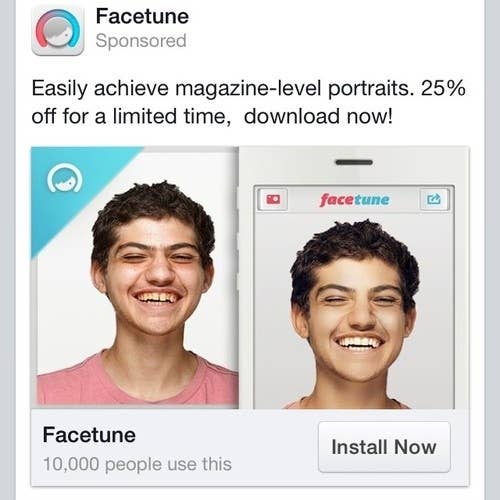

The Plastic Surgery App pitch is immediately divisive. Take this promotion, which has been bubbling up around Facebook recently:

Facetune has filters and basic photo editing options, and it has a faux-blur tool and a set of Instagram-ready frames. But the point of Facetune — and its competitors, like Modiface, Visagelab, iPerfect, and Perfect Photo — isn't to remove flaws from photos, or to enhance its basic properties. It's to fix the photos' subjects. Facetune turns yellow teeth white, removes acne, reduces wrinkles, shrinks or enlarges noses, turns up halfhearted smiles. It's somewhere between classic airbrushing and plastic surgery, except it's self-administered and nearly instant.

My first reaction to Facetune was revulsion. Repaired photos are fine, and so are enhanced photos. But this feels different. Trying it only intensified my worry: I immediately used it to whiten my teeth, and immediately felt bad.

Facetune creator Zeev Farbman defends the concept: "Different users use Facetune for different needs," he says. "You can use Facetune to remove minor problems that will disappear in a week anyway, try to elevate mundane photos into something that aspires to be art, or even create an alternative version of yourself."

"If I would need to give a physical analogue to Facetune it would range somewhere between a minimalist makeup and cosmetic surgery," he said, adding, "according to the user wishes."

Judging by the Facetune tags on Instagram and Tumblr, user wishes are varied: A lot of people go for the tried and true soft focus look, leaving telltale signs of airbrushing. Teeth whitening seems to be common, but facial reshaping is harder to suss out. There is certainly an aesthetic among people who overuse the tool, but photos on which it's been used sparingly can pass for real. It's used on children, and occasionally babies.

And of course these are the tagged photos — a Plastic Surgey App's idea use case does not involve broadcasting the fact that you used a Plastic Surgery App.

But it seems likely to me — based both on my knee-jerk, visceral response to the Facetune concept and on historical precedent — that aggressive photo manipulation like this might become the norm. Instagram didn't invent photo filters but it made them instant and shareable; these apps didn't invent airbrushing or photo retouching, but they adapted it for touchscreens and focused on the average user's biggest insecurities. Ratings for this class of app are high, but user numbers are still relatively low. Users, at least this early group, are open about how they use them: These are apps for fixing things that are wrong with them.