If Circa is successful, some very powerful people are going to get very angry. Words like "over-aggregation" and "stealing" will be used freely, and the "future of journalism" will be fretted for. And the naysayers, kvetchy as they may sound, won't be completely wrong.

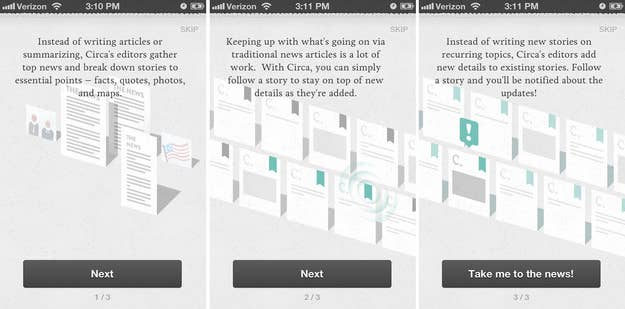

Created by Matt Galligan and Cheezburger Network founder Ben Huh, with others, Circa is a fairly straightforward app: It aggregates news into what it calls "Briefs," which are highly atomized articles divided into discrete units of information — a single quote, a new or changed fact, a map or possibly a photo — which are added in real time and disappear as you read them. The atoms, naturally, come from somewhere else. For now, Circa is about repackaging exclusively.

When I spoke to Huh, who is on the company's board, two weeks ago, he was strident about what the company was doing: Reinventing the news story, fixing what older media organizations had demonstrated they couldn't, and effectively doing it all on the backs of existing media properties. To hear him tell it, this was the logical endpoint of news aggregation — a risky move, he admitted, but also a "billion dollar bet." He sounded ready for a fight.

I spoke to Matt Galligan mid-launch, and he explained how the app, which is now live but having a bit of trouble due to high load, is intended to work. "We want to send people traffic," he said, "every single point has a source associated with it and read further if they want to."

"In a later version of the app we're going to call out great articles elsewhere that relate to the stories," he explained, adding, "journalism is an ecosystem, not any one thing."

The articles produced — or "built," to borrow a word from Galligan — by Circa's twelve editors are called Briefs, and while the form still needs a bit of work, its power is evident: rather than aggregating individual articles in the mold of vintage HuffPo, Circa aggregates around an entire subject, creating a sort of breaking news version of a Wikipedia article. Galligan welcomes the comparison, telling BuzzFeed "I think Wikipedia is a fantastic resource," and that "part of the app [is] inspired by Wikipedia."

He also welcomes, and makes, other surprising comparisons: "At the end of the day," he says, "people go watch movie trailers but they go see the movies. We're doing something that is not too far off what, say, CliffsNotes is."

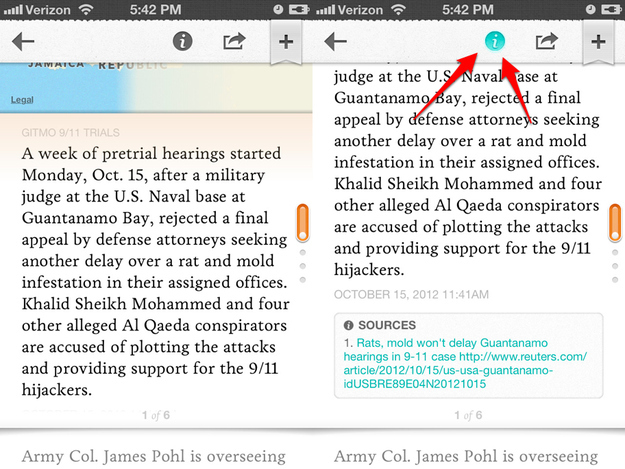

The concept is something of a paradox: If Circa truly finds a better way to present other companies' information, then the source links, which are present under each "atom" of the story, will cease to be useful, becoming little more than polite nods. If this form of the story really is better, why would you ever leave? It doesn't help that Circa's current design literally buries its sources, hiding them behind an ever-present button at the top of the screen. You could read an entire, 20-part brief and never see a source link if you didn't want to. It's aggregation without compromise.

"If someone is truly interested, they might [follow the links to] fact check us," Galligan said, assuring me that "we'll do everything we can to push them to deeper reading."

Eventually, Circa hopes to hire more editors to produce content in-house, setting Circa on a path not unlike Gawker Media, the Huffington Post or, yes, BuzzFeed, which started with lean staffs and a tendency toward aggregation and have taken steps to transform, to varying degrees, into reporter-driven news operations. But Circa's aggregate-then-dominate plan wasn't borne out of immediate necessity or a sense of experimentation; it was part of the plan from the very beginning. This, more than anything else, is what will give traditional media organizations heartburn. Circa is here to say, "you're doing it wrong." And then, in the same breath, "can we borrow some sugar?"

I asked founder Matt Galligan if he felt like he was throwing down a gauntlet with Circa. "We definitely don't think of it like that," he told me, "or at least I don't."

"Ben is very, uh, vocal about certain things when it comes to this stuff."

Of course there's a third possible response to something like Circa, and it's about mid-way between rejection and submission: licensing. "Should [Circa] take hold," says Galligan, "I don't want to be the only one holding onto these keys." If Circa can actually come up with a better version of the "news story," existing news organization may have no choice but to co-opt it — for a price.