On Nov. 3, 2013, a little-known website called ViralNova posted a story under the headline, "This Recently Married Man Just Realized Marriage Is Not For Him. You Have To Read What He Wrote."

As of today, it has been liked 973,000 times on Facebook. An unrelated BuzzFeed post published on the same day has racked up 286,000 likes, which correlated with about 3,700,000 total views. This would suggest that the ViralNova post has been viewed over 12,000,000 times. It was a monster hit.

The story is both jarringly new and eerily familiar. It is published on a site that clearly mimics the style, down to the font, of Upworthy, a new, wildly successful media company that specializes in packaging political and social advocacy videos in ways likely to get them shared on Facebook. (Sample headline: "What He Has To Say About Your Favorite Products And Brands Should Do More Than Worry You.") Slightly older internet users will recognize something old and essential about these ultra-sharable, context-free packets of emotion: They are, in all ways but technically, email chain letters. Consider how natural this looks:

Fwd: Fwd: Fwd: This recently married man just realized marriage is not for him. You HAVE to read what he wrote

The "body" of this post belies its roots: It's a first-person, life-affirming letter from a man you don't know but feel like you could; the font even changes to and from bold. Readers are given the courtesy of a source link, though it falsely claims to lead you to the "original" version of the text, which is a notional upgrade from the chain-letter days. At the end, rather than implore its readers to forward the message to their friends — at least 10, lest something bad happen — ViralNova asks its audience a couple questions: "Do you agree with him? Disagree? Share it on Facebook below."

Email chain letters thrived, and continued to thrive, for being compelling. But they were influenced by — and allowed to flourish within — a total lack of any meaningful context. The internet of the early '90s was a far-flung digital destination that was, for most users, hardly integrated with real life. And within that internet, email was more isolated yet: It was a discrete, dark back channel where information decayed as fast as it spread, where facts, claims, and their sources are at rest in a state of separation.

Snopes was the answer to chain-letter internet, where sentimental, truthy forwards were flanked and often overtaken by messages of a more sinister variety: the "Vince Foster's Friend and CONFIDANTE Speaks OUT FOR THE FIRST TIME!! Please Pass This On" types of messages, which took advantage of email's relative isolation from the world, and distrust in media, to spread appealing falsehoods.

If my inbox is any indication, however, these particular types of chain letters have fallen to the wayside. Why? Email is now as much a part of the internet as search, which tends to be fatal to the conspiratorial style of chain letter, which now must be exceptionally sensational to warrant a "what the media has been hiding" angle. Likewise for the get-rich-quick chain letters, which have been replaced with hypertargeted fraud, or phishing.

But chain letters of the heartwarming variety are as strong as ever — perhaps stronger — having successfully passed from email to the internet, and from the internet to Facebook. For a casual Facebook user, verifying a post and sharing it are both easier than than ever before. But one of those two things is still significantly easier than the other, and Facebook's rewards system favors the latter. A feel-good post must only be countenanced to be shared. Verification is for killjoys. Besides, what would a Snopes for ViralNova or Upworthy even look like? It could question the sources of the stories and the details of the anecdotes, or provide context for their claims. But could it correct sentiments like, "man is fundamentally good" or "we should do better?" A site specific to this purpose would be more un-viral than anti-viral. Correcting a post like this is like fact checking Chicken Soup for the Soul, or refuting a prayer.

And in any case, the rise of the Facebook chain letter was inevitable. A prophetic Alt.folklore Usenet post from 1994 formulates it as a rule: "In every Paradise there is at least one fatal flaw. In every mail system, there is sooner or later a chain letter." Facebook has finally settled on its own.

At their best, the new internet chain letters are sincere, accurate and only mildly manipulative: a stray dog rehabilitated; a life turned around; a prejudice overcome. They can be good! When the post itself, or the linked video, is factually accurate, the worst sin you can accuse Upworthy of committing is one of style and taste, of being cloying or emotionally exploitative. Objections to, or affection for, the best of Upworthy-style pass-it-along content come down to matters of personal preference. Ezra Klein's own take on the concept, Know More, which was launched under the auspices of the Washington Post, is instructive here.

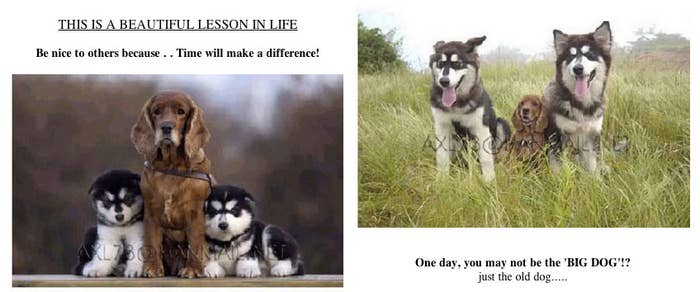

Virtually every media company dabbles in this kind of post, present company clearly included. At the fringes of the new chain-letter movement, however, is where you find the most explosive stories — where sentiment overpowers the concepts of fact and fiction. These manifest naturally as text-only Facebook image memes with inspirational sayings and powerful images reassigned, almost at random, a new, shareable frame of reference.

This is where the pure spirit of the chain letter lives on, untouched, and where an immense opportunity waits for savvy or cynical publishers — or republishers. Or should we call them unpublishers? ViralNova is best described as a basically invisible secret tunnel between the dark internet — chain-letter internet — and Facebook; in its own FAQ, it defines itself in strictly negative terms.

As hipster as it sounds, ViralNova doesn't fit into a category. There's no reason it has to either. We aren't a news source, we aren't professional journalists, and we don't care...

Q. Can I interview someone at ViralNova?

A. Probably not.

Another way to read this: ViralNova does not exist. Those who speak of ViralNova miss the point of ViralNova.

Take the newlywed story. A footnote at the bottom of the story says, "This post originally appeared on ForwardWalking.com, a website dedicated to helping people move forward in life." This website is loosely associated with an organization called the ANASAZI Foundation, which bills itself as having "outdoor behavioral healthcare services [that] are ideal for adolescents (12-17) and young adults (18+) struggling with lack of motivation, defiance, mild mood disorders, drug and alcohol experimentation, internet addiction, entitlement issues, and other self-defeating behaviors."

This is a classic chain-letter attribution chain: long and weird, winding through the wilds of the self-help internet (the post went viral multiple times, in multiple forms, before going mega-viral as a story about "This Recently Married Man") and ending at some sort of affirmative nirvana, an aggressively pleasant place where the world's headlines — not just subject lines — are exactly as they should be, despite the odds, and where the things you believe should be true are true. Or at least true enough.

Previously: Ban Headlines.