Here's a question: What exactly are headlines for, on the internet?

This post doesn't have a canonical headline (that is, a single, main, authoritative headline, chosen by me, that isn't a joke). But it has a large number of other headlines that you can't see right now. It has, for example, three headlines on the BuzzFeed front page, none of which are attached to this post when you actually arrive at it, but which will be shown to different visitors to the main page of this site (the idea being that the least successful headlines are culled). Those headlines serve a purpose to me: to get you to this page. Once you're here, though, their use is fulfilled. They don't need to continue to exist, and in our system, they don't. Those frontpage headlines are replaced with the main headline which, at least on this post, unusually, doesn't really exist. But why should it?

This post will also spawn a multitude of headlines on Twitter and Facebook — I started with "Infinite Test: Why We Don't Need Headlines Anymore," and "RIP Headlines" on Twitter, because I thought those were both fair representations of the post and might get people to read it.

For someone to read one of those tweet headlines and to come to this piece would be a small success — that is clear. What isn't clear is why I would want those people to come to the story and find another, similar-but-different headline. To click on "RIP Headlines," a headline, and arrive at a page that has another headline, along the lines of "Why We Don't Need Headlines," is something we're very used to doing. But it should feel like a form of deceit. It tells a reader, though you might not receive it this way, that the headline you were initially interested in isn't as good as the original headline — that the one you were interested in is not the best one, just the one we thought you'd be interested in. Or, to put it another way: you're not good enough to be interested in the best headline, but maybe this lesser one will do. We have ours, you have yours. Ours is the most right. But welcome to our website! Please click the ads.

If you consume much of your news through Twitter, as I do, you often see two or three headlines for a story before you ever see the story (and you probably accept the premise that website front pages are dying, or at least becoming less important). Here, for example, I saw a tweet with the headline: "Artisanal refuses to die," tweeted by a the story's author. The headline on the site, also presumably by the story's author, is "Artisanal Won't Die." When I tap on it, I see no fewer than three headlines when the story loads: the one in the title bar, the one in the tweet, and the one on the page.

Twitter's app makes literal the context we almost always have when we discover a story — a process that increasingly feels like hearing a book read aloud by a child: "Moby Dick, by Herman Melville." *opens cover* "Moby Dick, Published in whatever, by Herman Melville" *turns page* "Moby Dick, Chapter One. Ok. Ready? Ok. Call me Ishmael."

Headlines, in their original 17th-century form, existed to tell you what section of a book you were in and what page you were on. Usage of the word in a newspaper context came later, in the 1890s. Then, their existence was justified because it had been freshly born of necessity: if your primary mode of story discovery is to look at a newspaper frontpage, you need headlines to tell you where to go.

That function, now, has been largely outsourced. On a site like BuzzFeed, or the New York Times, the front page headline still serves that diminished original purpose (and as long as we have front pages, it always will). But for many stories — a growing number — that headline is not the most important one. The headline that's most successful on Facebook or Twitter, or in a link from another site, is that story's headline *by default.*

This might seem like a subtle change, but it's experientially significant. When someone arrives on a story, the headline they followed is the only headline they need to see — to show them another promotional headline is to oversell or tell them they've been misled; it's like welcoming someone to a "casual get together" by saying, "welcome to Joe's birthday party."

Canonical online headlines, at most, tell you you're in the right place; that the tweet you followed was not a lie. But headlines as we write them today aren't even very good at that. If they're nü-internet-style headlines, they're sales pitches or orders (see Choire Sicha's fantastic Take A Minute To Watch The New Way We Make Web Headlines Now from a couple weeks ago). If they're classic, print-style headlines, they're meant either to stand out in sea of text or tease you into reading more (online, however, the choice has already been made — you chose to visit the page). What stories on the internet need, then, is not a headline but what's known as a dek — a simple description that both confirms the remote headline and adds to it. A boldfaced introduction, in other words, that flows seamlessly into the first sentence. There's no need to reset with yet another headline.

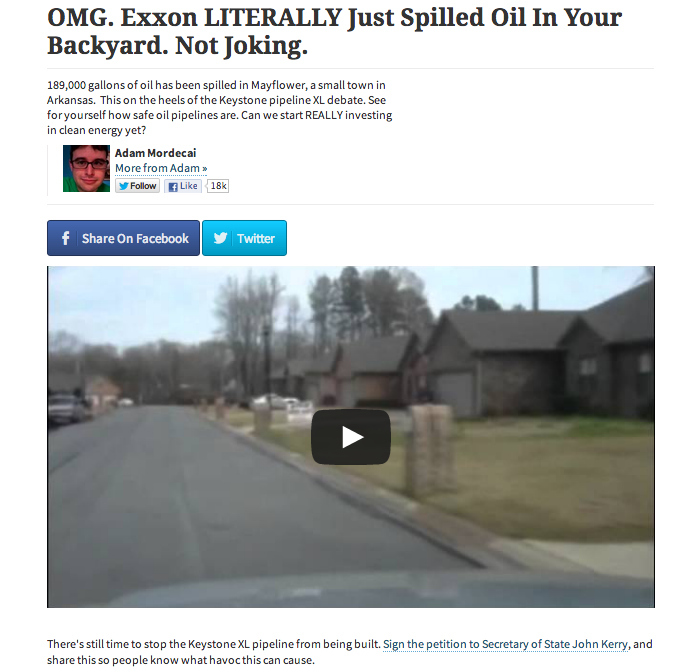

From a writer's perspective, maintaining your own authoritative headline may be a way to assert your taste, or message, over the tastes and messages of the thousands of people sharing or aggregating your story, photo or video. (It's not always easy to see how people tweet your stories; while it's nice that they're reading, and showing them to people, they quite often zero in on the part you're least interested in or proud of). And "outside" headline writers don't follow the same standards as someone accountable for the story might, so it's easy to understand unease in relinquishing the headline to them; Upworthy, a sort of reductio-ad-absurdum experiment for this concept, sometimes tests dozens of headlines for its aggregated stories, which are then targeted at Facebook, and settles on the most effective, whether or not it's even accurate:

This headline, while effective, is pointedly misleading. Unless you live in one of those houses, Exxon did not spill oil in your backyard! (Even then: FRONT YARDS). The video is compelling enough, however, and the message do-goody enough, that most people don't appear to feel betrayed. (Headlinese, since its earliest days, has proudly flouted grammar for brevity and efficacy. Headlines are not grammatical! They are incorrect! But misrepresenting facts is a different matter.)

But the problem with the page is the headline; one that you might forgive a Facebook friend for sharing or even writing, but one that a professional publication would normally cringe at publishing. The dek — that intro — on the other hand, is fine. Consider it again, with no headline:

Again, the viewers are already here, and probably saw that first headline (or another similar one) on Facebook or Twitter. Its presence on the page caused a serious problem and solved none. Its absence sacrifices nothing, and actually hides the (slightly ugly but self-incriminating) truth of how you got to the story in the first place.

(It may be worth noting that the Upworthy video has, in addition to the thousands of social media headlines, had more than a few canonical headlines as well, including at least two on YouTube. It's a rip of a rip of a rip of the original, it appears.)

This is all to say that, online, headlines are not part of stories; they exist outside of stories. Their former three-pronged role, as place-marking buoys and summaries and introductions, has been largely mooted: The place-marking is done on a front page, on Twitter, on Facebook or elsewhere; the summarization can be taken care of with a dek or dedicated intro (which is written accurately and in grammatical English, not headlinese) or a first line; and the introduction, at this point, has already been made with the remote headline.

Today, canonical headlines are no better than tags, or suggestions for tweets.

So let's get rid of them. Let's Tumblrize the internet.