Say you're a rich person. In particular, you're the kind of rich person who likes to buy the best stuff. You drive an Audi with a special suffix, live in two or three tremendous houses, and cook with a kitchen full of $300 pans. Your kids play with a tiny, stupid purebred dog, and have tutors with PhDs. Somewhere in one of your basements, there's a mechanized massage chair with built-in speakers. Everything you have is better than the things everyone else has. Except your gadgets.

In the most important categories, real rich people tech doesn't exist. There is no better phone than an iPhone or the best Android or Windows Phone. There is no better everyday laptop than the major companies' flagship models. There are fantastically expensive TVs, of course, but the best one for your bedroom's $8,000 ivory-inlaid mahogany entertainment center isn't going to cost you more than two grand. The best tablet? $500, or a few hundred more if you want extra storage. The best wireless internet connection? Less than $100 a month. A desktop that can play any game for the next three years? $3,000. The best desktop for doing anything else, with the best spare monitor? Same.

I suppose you could buy a $20,000 pro camera or spend a fortune on audio equipment or extravagant home entertainment systems, which are priced specifically with rich people in mind. But most of the core of the luxury segment, as analysts like to call it, is basically dictated by Apple's price tiers, which means it's accessible not just to the rich, but to the middle class. There's no VIP section in tech hardware, no credible Rolex or Ferrari or Hermes. The biggest companies make the best products, and they don't charge very much. A CEO of a Fortune 500 company quite possibly has the same phone as his driver, who has the same phone as you.

Gadgets are better when they're precisely and uniformly assembled, and require advanced manufacturing techniques as much as they require careful design. Great new gadgets routinely require entirely new manufacturing techniques, which means they require hundreds of millions of dollars to launch. That's why you can't hand-craft a better cellphone, and even if you could, you'd have to hand-craft better software than Google and Apple and Microsoft's multi-billion-dollar R&D departments.

That's also why those super-expensive phones — think Vertu — never made sense. They're usually just jewel-covered feature phones, which makes them worse than the worst smartphone you can buy at any Verizon store. They're $10,000 Skymall products. You only buy them if you're rich and stupid, which is probably why they're fading out of existence.

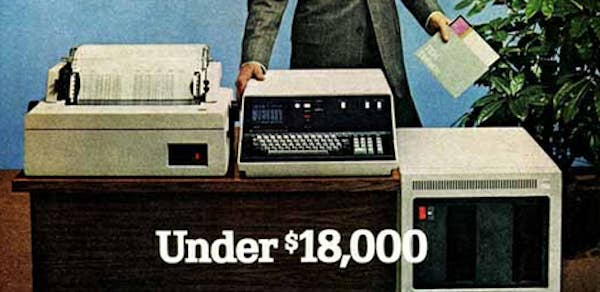

The flattening of the gadget market is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before, oh, 2005, there was a tier of products for rich people: new things. If you were rich in the late 70s, you got to be the first person at your country club with a PC. In the early 90s, you might've flashed a laptop at your jetsetting buddies. You had a cellphone before anyone else, and a BlackBerry before smartphones took off. Being rich let you live in the future, with tech categories that had just been invented.

Now, "living in the future" is a privilege of the middle class — it's buying a Retina MacBook or a smartphone or a Kinect or a set-top box. The rich can buy more of these things, and surround them with more accessories, but they're the same things.

***

That doesn't mean that being rich doesn't buy you something, or that the future of technology is fully democratized. Money buys you constant upgrades, and the luxury of ignoring timing. You don't need to wait for your cell contract to expire to get a new phone; you can just eat the upgrade cost or buy out the rest of your contract. You can buy a new gadget knowing it'll be obsolete in six months without feeling buyer's remorse, or experiment with a whole new platform without considering its future. Who cares if Windows Phone tanks? You can do with your Lumia what you did with your Pre: throw it in a drawer, where it'll sit until its battery explodes.

But it's not just about hardware anymore, and hasn't been for a long time. In 1990, a concerned reader wrote to the New York Times:

While I share William Safire's worry about innovative telephone technology becoming an ''electronic peephole'' in ''Trace That Call!'' (column, Dec. 11), he fails to mention the most distressing aspect of the new gadgetry: that it assures a right of privacy only for those who can afford it.

...

Should privacy really be a luxury that only the wealthy can afford?

22 years later, the idea of an elite private version of Facebook, or an expensive private web browser, sounds absurd, and our notions of privacy wouldn't even be coherent by the concerned reader's standards. But he wasn't quite wrong — having money increasingly buys you a different experience with the same hardware. It's not call-blocking, it's no-strings-attached content.

Money buys you every movie you want, and every show. It buys you all the music in the world, and subscriptions to every publication. It buys apps — that's the big one — that can utterly transform a device every week you own it. Most importantly, it gets you these things without ads*. I spent hundreds of dollars on a-la-carte apps and content last year — nearly a thousand. If I didn't have to worry about money, I would have spent much more.

So maybe in absence of better electronic things or a head-start on your neighbors, that's what wealth assures you of: a sickly, and distinctly modern, version of privacy. Privacy for you and your content.

*A study by the Luxury Institute found that wealthy smartphone users love downloading apps for their favorite brands, however. But those "ads," at least, are a choice.