Earlier this week, Howard Lindzon, cofounder and CEO of Stocktwits, watched the concept he had built his company on — the "cashtag" (see: $AAPL) — get incorporated directly into Twitter. He was furious:

It’s interesting that Twitter has hijacked our creation of $TICKER ie. $AAPL. It only took four years to ‘fill‘ this hole, though a few months back they told me in a detailed email it was not a hole they wanted to fill.

You can hijack a plane but it does not mean you know how to fly it.

Twitter has a history of doing this. In fact, it's how modern Twitter came into existence. Hashtags, retweets and even @ replies weren't part of Twitter 1.0 — they were only added after people started using them on their own. Twitter was basically nothing but a text-posting service; the users built it as much as the company did.

Lindzon's anger is perfectly understandable, and he probably deserved more warning than he got. But we're going to hear plenty more reasonable stories like his as Twitter clamps down on API use, slowly but surely (this is going to happen) eliminating the majority of 3rd-party apps.

This isn't just about Twitter, though. The pattern of fostering a community of people to essentially do your work for you — to assume the risk of trying new ideas, without any guarantee of safety — leads to these types of moments happening on a near-weekly basis to people who've developed apps for Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and others.

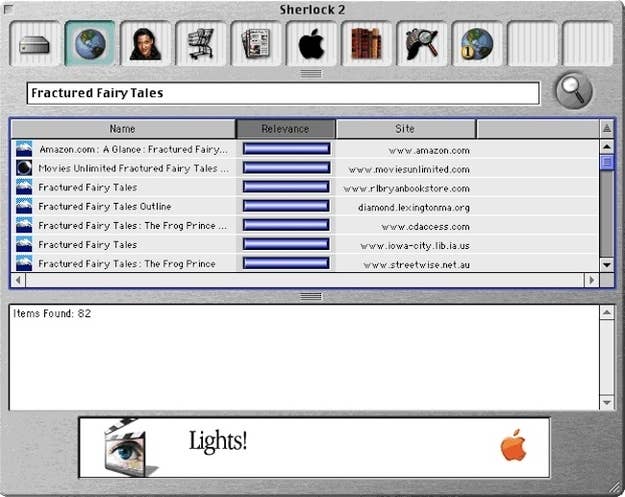

In fact, this process is so routine that it has a name: Sherlocking, after the much-loved app (Watson) that Apple rendered obsolete with an update to Sherlock, the built-in Mac search tool that lives on, in part, as Spotlight.

But it's not only the process that demands a name. The most important companies in tech have, to varying extents, intentionally built their modern selves on a sort of Sherlocking model, giving people the tools they need to expand on the original concept, and just enough time and freedom to see the new concepts through — to prove them.

This is a type of company. Let's call it Freesearch and Development company.

This, in part, is why Dalton Caldwell's anger is so deep: it's based on an existential fear. This week, the entrepreneur posted an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg, relating a story about how his meeting with Facebook about his in-development Facebook-based app resulted in an instant job offer — not because they were interested in his idea, but because it overlapped in part with something they were already working on.

Then, of course, there are the Apple events, the venue of the original Sherlock, where the stakes are highest and fear is basically part of wearing a dev badge: almost every time Apple announces a new update to iOS, it does so at the expense of developers whose apps used to fill the operating system's gaps. It's easy to forget that the iPhone didn't used to have a to-do app, homescreen notifications or iMessage. It'll be just as easy to forget, after iOS 6 is publicly available, that turn-by-turn navigation used to be something you had to pay for. Hell, it's easy to forget that it didn't have official apps for a year — the jailbreak community helped prove how powerful they might be.

And as the industry consolidates around a few continental superpowers, it's becoming clear: this is the only way to win.

***

Here's how to become a Free & D company:

1. Make a cool thing that everybody wants

2. Get a whole bunch of people to sign up for or buy your cool thing

3. Make updates to your cool thing infrequently and cautiously, or ignore loud, but potentially risky, requests from your audience

4. Let other people update your cool thing. Give them cheap or free tools, as well as motivation, to do so.

5. When these other people come up with a really cool idea for your really cool thing, take it from them. Buy it if you must, but steal it if you can. After all, it's part of your product — the idea was never really theirs in the first place. Your original idea, the thinking goes, enabled, and therefore contains, all derived ideas.

Twitter releases official apps. Facebook makes (then buys) a photo sharing app. OS X adds notifications. Safari adds a "read later" function. iMessage clobbers dozens of free texting apps with millions of combined users. Large companies effectively nationalize the industries that were thriving within their borders, with profit and users taking priority over developers by default.

Twitter's cool thing is Twitter. Facebook's cool thing is Facebook. Apple's cool thing was the iOS. All cool and dependent things that that these cool things inspire aren't just vulnerable to being absorbed — if the idea is good enough, and vital enough, absorption is an inevitability. It would all seem like a big trick if it weren't so obvious and people would stop indulging these companies if there weren't a better-than-awful chance of getting rich anyway, either from short-term success or a buyout.

There are degrees, however: Apple has to keep a good relationship with developers for the long term, because the existence of third party apps is their platform's ultimate feature; Facebook, perhaps with less to gain from discrete apps, doesn't need to care nearly as much; Twitter, which is in the process of reducing its entire app ecosystem into a series of unmonetizable plugins, doesn't have to care at all — it's burning bridges it just doesn't need anymore. The companies that don't do this at all are smaller in both mission and size: Craigslists never allowed developers, and when it shuts them down, doesn't take their ideas; Tumblr has never fostered a Free & D community, but then again, Tumblr, which launched right around when Twitter did, is still just Tumblr.

Twitter and Facebook and Apple and Google and Microsoft haven't simply become as successful as they are because they came up with great ideas. A tremendous and increasing part of what they do is let other people come up with great ideas for them — to rent profitable space on their service, or bask in its glow, in exchange for doing the hard work of figuring out what comes next. That's the essence of Free & D, and a defining trait of today's, and probably tomorrow's, most powerful tech companies.

Update: BuzzFeed dev dude Finn Smith reminds us of a pithy summation of this idea by an Microsoft executive in the late 90s: "embrace, extend and extinguish/"

The main difference, I think, is that when Microsoft was seen as doing this nearly 20 years ago, the government opened an antitrust case against them. Today, it's almost routine.