Microsoft is buying Nokia's cell phone business and licensing its patent portfolio, according to both companies.

In 2003, Nokia's cell phone market share exceeded 35%. That same year, its phone business alone posted an operating profit of 5.48 billion euros. Today's sale price, which includes 1.65 billion euros in patents, is just 5.44 billion euros. It's been a rough decade.

Nokia's cell phone collapse has been a spectacular one. The Finnish giant dominated the dumbphone era after Motorola, another faded star that recently fell into the hands of a comparative upstart. But it was blindsided by Apple, then deprived of a chance to regain its footing by an even more aggressive Google, which followed close behind.

The story, in hindsight, is simple: Nokia did not have a truly compelling smartphone ready when a large segment of the developed world was first compelled by smartphones. Whether this was the result of complacency — Nokia was, in the mid-2000s, the leader of the niche smartphone category — doesn't matter now.

Nokia's miscalculations became impossible to ignore in 2008, the same year Microsoft decided, internally at least, to scrap its ancient and inadequate Windows Mobile platform in favor of something entirely new. Under these circumstances, it's easy to imagine how a sort of camaraderie might have emerged at the time, or at least a mutual sympathy. Certainly a shared interest: to break back into the market from which they had been unceremoniously expelled.

During the next two years, while Microsoft readied Windows Phone 7 and Nokia floundered on, the seeds of Sunday's deal were sewn. A chastened Nokia was a natural partner for the tardy but determined Microsoft; it needed a software solution and Microsoft needed help with hardware. The 2009 vision of 2013 renders clearly: Two giants, united after some missteps, regain their rightful place. By 2010, when the head of Microsoft's Business division left to take the helm at Nokia, the gears were moving. Many at the time wondered if Stephen Elop's time at Nokia would be spent grooming the company for purchase — a foreigner in all possible ways, he began his time at the company with a memo rightly but offensively declaring Nokia's proud platform a failure, and quickly pledged the company's commitment to the still-tiny Windows Phone. It felt like a radical about-face, but no matter: Nokia and Microsoft were going to save each other.

Now, with Elop returning to Microsoft after a job well done — well, a job, done —that plan has come to fruition. The only problem is that there's little left to save. Windows Phone has barely dented the now much larger smartphone market. Nokia hasn't had a Windows Phone hit. This incongruity — between a successfully executed, slyly strategic long-term merger plan and a much grander, more general sense of failure — might explain Microsoft's deeply strange and somewhat sad stated goals for its Nokia acquisition.

Microsoft' s "Strategic Rationale," titled "Accelerating Growth," is a disjointed and bizarre document. It manages to sound both insane and uninspiring, outlining modest goals that still sound unrealistic.

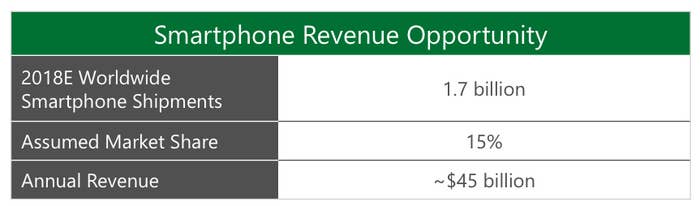

For example, it lays out a plan to pull in over $45 billion dollars in smartphone revenue by 2018. But it plans on doing this by securing just 15% of the projected global smartphone market — not exactly a world-beating plan, keeping in mind the time frame. Consider: 2018 is five years away. Five years ago was the year the App Store first opened.

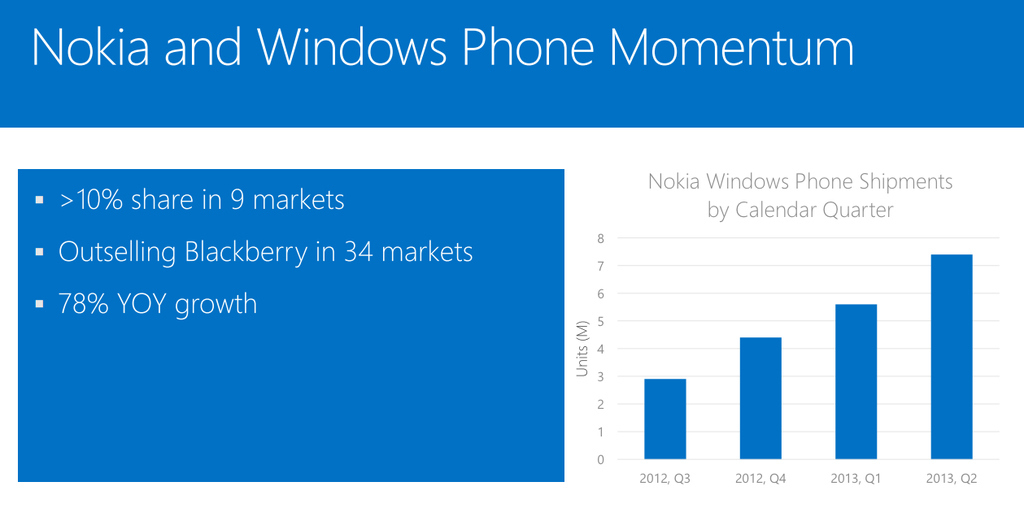

To paint a picture of growth and health, Microsoft then touts Nokia's Windows Phone shipments, comparing them not to Android or the iPhone, but to BlackBerry, which is teetering on the brink of collapse. Samsung shipped more Galaxy S4s in its first month than Nokia shipped — not sold — Windows Phones in the last quarter.

Then there's this contorted projection, that some imagined future explosion in smartphone sales — which were earlier limited to 15% of the world market — would boost Microsoft's struggling tablet business, which would in turn help its profitable but profoundly future-blind PC business. What?

It's a fitting end for the close of Microsoft's Ballmer era, during which the company gained then lost cachet among consumers and missed out on the most important change in consumer electronics in decades, but remained incredibly profitable by succeeding in other, less glamorous areas. His letter to employees is only technically optimistic:

This is a smart acquisition for Microsoft, and a good deal for both companies. We are receiving incredible talent, technology and IP. We've all seen the amazing work that Nokia and Microsoft have done together.

Microsoft is a powerful, diverse company that missed smartphone revolution. It may never recover that loss, but can easily recover from it. And it could accomplish interesting and unexpected things with Nokia's phone business, particularly in the developing world — an idea that is barely given lip service in the presentation. Its valuable patents and their licensing possibilities were given much more attention, as was the implication that per-device margins might climb under the new arrangement.

There is a substantial chunk of Nokia that Microsoft is not buying, a multibillion dollar business on its own, which is primarily concerned with cellular networking equipment and mobile network deployment and management. Nokia Solutions and Networks is the kind of subsidiary that lands contracts to bring mobile broadband to places like Iraq — a complex, bottom-heavy company but one with an eye for opportunity and risk. The other Nokia, the one Microsoft isn't buying, is the kind of company that at least still has a shot at getting in front of the next big thing.