Kiva, the online micro-lending organization, has been criticized for two main reasons: ignoring users in its own back yard and relying on middlemen loan institutions to manage money.

That's, in part, why Kiva Zip exists.

Even in the United States, many of the microfinance institutions (MFIs) Kiva works with charge interest ranging from 4 to 10 percent (a rate the lender is hardly aware of). The average interest rate of MFIs Kiva uses overseas is much, much higher. Most of the MFIs are nonprofits using the interest rates to pay for overhead—but it still makes a dent. Plus, partnering with outside financial institutions brings baggage; namely, an an institutional aversion to risk.

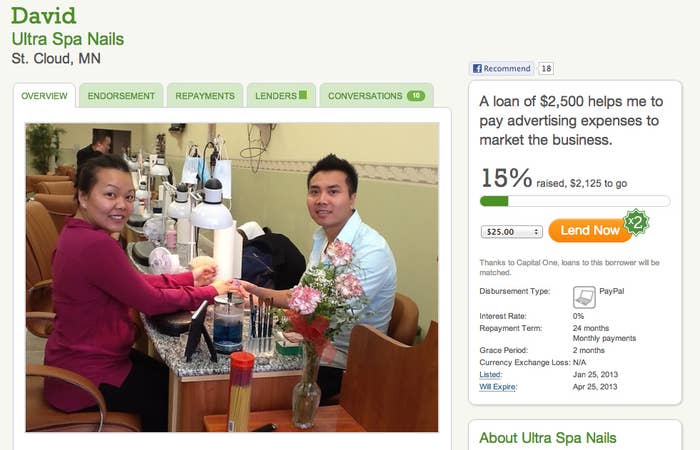

Kiva Zip, a straight up peer-to-peer lending service launched in the United States and Kenya, takes out the MFIs entirely. It's still in early testing, and Kiva is keeping it somewhat on the down-low. But the service has already resulted in loans totaling $400,000 to 135 entrepreneurs in 28 states, as well as around 424 loans totaling $81,550 in Kenya.

The loans are zero-interest, and anyone is eligible, regardless of their credit score. To be listed on the site, the borrower only needs a vetted "trustee," as Kiva calls them, whose relationship to the borrower can range from teacher from a work-training program to a pastor—or even someone who has successfully paid back their own Kiva Zip loan. Once the borrower has placed their profile on the site, anyone can click and give them a loan starting as low as $25. The trustee has no financial obligation if the loan isn't repaid; the system, like classic Kiva, relies mostly on trust.

"One big breakdown in the market is that credit scores are based on an algorithm that doesn't capture who you are," says Kiva President Premal Shah. Instead of an algorithm, the loan is granted based on investors' own criteria — Yelp ratings, some subjective quality of the idea, their grades in a training program, the entrepreneur's personal character, or a simple hunch.

There's more than a hint of social media utopianism in what Kiva is doing. "You think about LinkedIn and social graph. It's all about who is connected to whom and who will vouch for whom," says Shah. "Say you have a housekeeper. If you trust her with you keys, maybe you would vouch for her."

It's a bit like the Kickstarter model, except the money gets paid back. Kiva's model is also naturally more inclusive; where Kickstarter favors good self-marketers with extensive online networks, Kiva only asks for a good word.

Take Victor Chicero, who grew up in a coffee-growing region in Mexico. When he came to the U.S. in 2001, he worked a series of odd jobs, eventually landing a gig at a coffee shop through the pastor at the local church. He didn't have formal education past the age of nine. But he wanted to open his own cafe, so Chicero took a course at the Mission Economy Development (MEDA), a small business incubator for Latinos in San Francisco. It was there that he found trustees for his posting on Kiva.

Chicero borrowed $5,000, opened Cafeto Coffee Shop, which was a success, and paid back the loan. He's now signed up for another Kiva Zip loan to open a second location.

Based on Chicero's success, he is now able to vouch for other people in his neighborhood. Rocio Hernandez, a single mom from Mexico, was able to buy a car to expand her house cleaning business. Ernesto, who worked as a dishwasher when he first emigrated from El Salvador, was able to invest $5,000 in a taxi medallion. He has, in essence, built a tiny, ad-hoc credit ratings agency from scratch.

It remains to be seen what the cost of this altruism is. Credit scores, as ruthless as they can be, serve a purpose — so far, the repayment rate of Zip loans in the U.S. is 90.5 percent. Critics worry that the trustees' lack of material accountability limits their usefulness.

But like Kickstarter, Kiva's secondary function is pre-loading interest — or building buzz — about your business. And with that buzz comes an informal accountability: "You have an internet community that has basically made a bet on them," says Shah. "They saw your potential and it makes you want to try harder and be the best. If your friend or favorite teacher vouched for you, you want to step up and pay them back. It sounds cheesy to say that, but it really works."