Last week, Peter Shih became the lightning rod for San Francisco's animosity against the influx of rich techies. For longtime residents of the Bay Area, the tensions between the tech crowd and its critics is not just an ongoing struggle, but a pastime of sorts. Apps, Google buses, and twentysomethings with no respect for the city's culture are taking over, says one side, while the other sees the start-up/tech crowd as a force for good in the community. While many of the city's problems stem from the area's giant tech companies, they're largely a result of complicated city politics and real estate issues, not the fault of individual techies.

Nevertheless, the Shih flyers were notable, not as the latest in a series of conflicts, but because they stood out as a rare offline manifestation of the city's mounting tensions.

While there have been a few "real world" demonstrations — the May Day Occupy protest, during which some anarchist activists graffitied buildings and smashed car windows, and the much hyped, but poorly attended Google bus piñata protest — most of the debate happens on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, or blogs, often via iPhones. The irony isn't lost on the protesters, but the clash feels more real online than in the neighborhood streets.

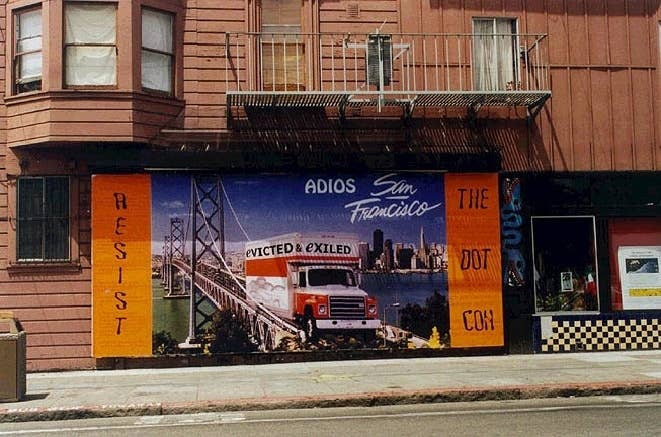

The Shih flyers, though, are reminiscent of the last dot-com boom, where the schism between the two communities was more pronounced and its effects much more tangible. The internet was new, the bubble more absurd, the companies far more ephemeral, the sector smaller.

It was the days of Xerox machines, not hashtags. Anti-tech posters, wheat-pasted to walls and taped to street poles, weren't one-off incidents, but a common form of neighborhood protest.

If you lived in the Mission in the late '90s or early '00s, as I did, you probably remember the posters by the Mission Yuppie Eradication Project and the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition, which were plastered around the neighborhood.

It was a different era of protest, when we didn't live and fight online. Frustrated citizens were required to go to greater lengths, rather than just hitting the "like" button. The protests and posters certainly didn't force the first tech bubble to burst, but they did effect the culture.

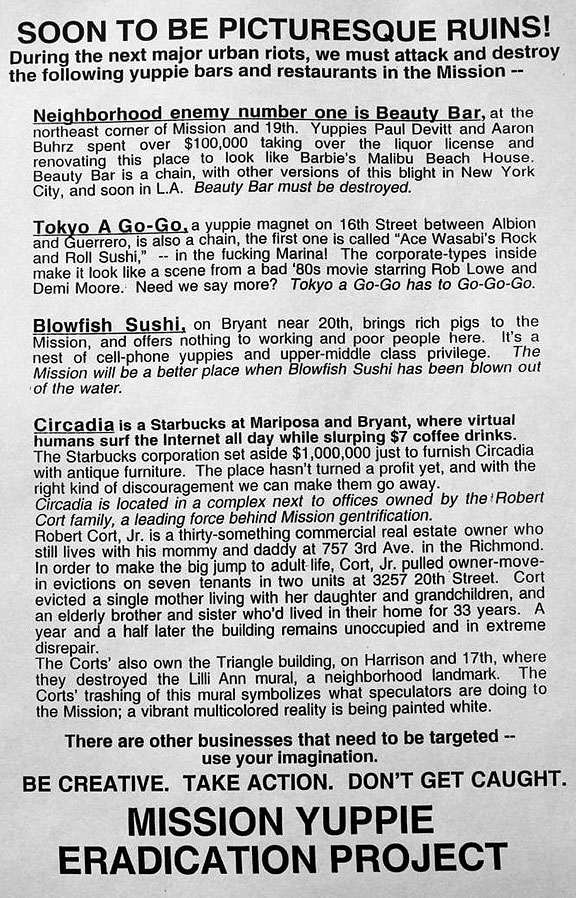

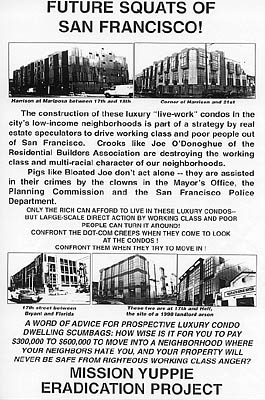

A far cry from today's socially driven events, during the early protests angry residents screamed at "yuppies" on the street and keyed SUVs. Feces were smeared on the homes of dot-com targets, and paint-filled balloons were thrown at their doors. People graffitied dot-com office buildings and the businesses that catered to their employees. Street protests were common then, as were arrests. During one protest, an angry mob blockaded a bunch of dot-commers who were living illegally in live-work lofts created for artists, one of the hot-button issues involving displacement at the time.

A 1999 San Francisco Chronicle article, "Battle Over Gentrification Gets Ugly in S.F.'s Mission," quoted the owner of the Beauty Bar (described as "a yuppie haunt" in the article): "The posters about being creative and taking action really made me nervous, because people can take that to heart and really do some shitty stuff. My bar was tagged some weeks ago with a warning that we should leave the Mission or else face the consequences."

The same article quoted a member of the Mission's Eviction Defense Network, who described the posters as "a symbol of a lot of long-term residents' frustrations with the parasitic institutions and the fear that goes along with knowing that you and your loved ones are being pushed from the neighborhood."

Today it seems the promise of the first web boom largely came true and much of the protest has moved to the internet. Even for the critics, technology is a ubiquitous, dominant part of daily culture. The city's largest tech employers aren't going anywhere. Some areas — the Mission in particular — have arguably tipped in favor of the dot-commers. The restaurants and bars that were once deemed the enemy are now the small businesses that concerned citizens are taking to the internet to save. The flyers may be back, but at best they're a throwback to a different age.