In India, adding a wig or mustache to a photo of your friend's favorite celebrity or politician and posting it on their wall is almost guaranteed to make them report it to the Facebook authorities: Nearly a quarter of photos being flagged in India are such photoshopped images.

Facebook's giant new cultural challenge isn't just that people constantly flag photos which don't actually violate Facebook's community standards. It's that every culture has different reasons to flag photos.

"We have an assumption of how people might use Facebook and that isn't the case," says Jake Brill, one of the Facebook employees working on a project to address the issue. "It's fascinating how much cultural specificity there is in how people take offense to different photos."

Overwhelmed with people flagging photos for removal, Facebook noticed that the majority of the them weren't violating the community standards — images depicting things like porn, violence, self-harm, drugs, intellectual property, or privacy violations. Instead, in the U.S. where the majority of users are, most of the reported photos depicted the person flagging the photo — in an unflattering or embarrassing way. As Facebook's researchers dug deeper, they found that people were also reporting photos of their exes with new girlfriends, photos of "besties" which didn't include them, and images of children which they wanted to keep private. Especially amongst teenagers engaging in mean girl behavior, things got complicated. What they were reporting as hate speech were really just examples of their classmates being mean.

People around the world flag very different types of stuff. In the U.S. and many English-speaking countries people post about their personal lives — vacations, parties, baby photos, food. But in other markets, like India, where people post about their interests, ideas, and values — not themselves — the photos that get flagged are unpatriotic or offend people's religion or public figures.

Facebook won't censor photos that don't violate its community standards. But it still wants to give users better tools to report what they don't like and actually do something about it.

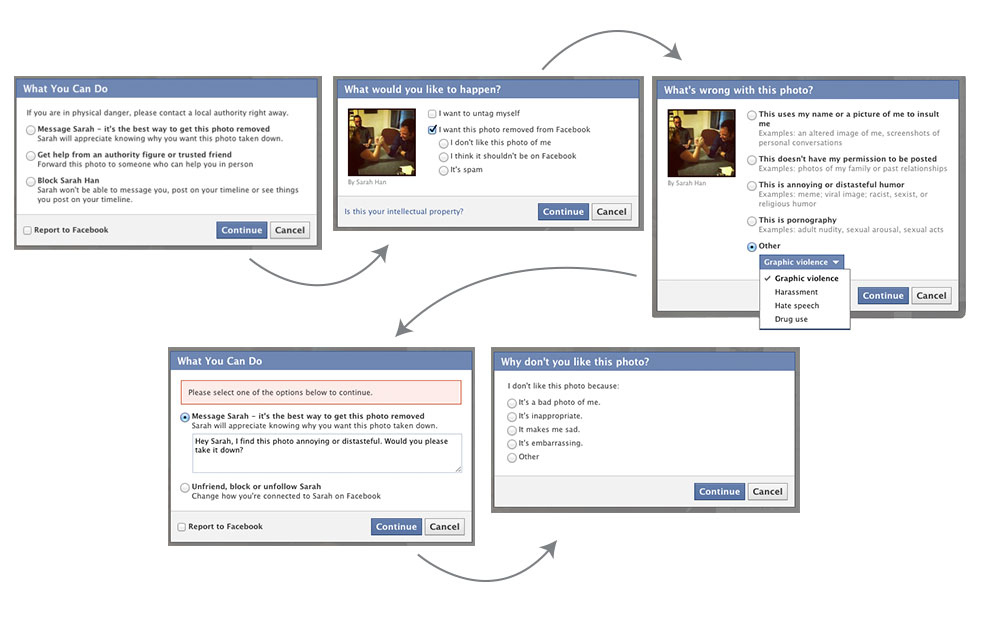

Collaborating with social scientists from Berkeley, Columbia, Yale and other universities who work on theories about conflict resolution, altruism, compassion, and cyberbullying, Facebook recently launched one part of its solution in the U.S. When users flag a photo, Facebook offers a set of categories to explain why they are flagging photos, like "this photo embarrasses me," it "uses my name or a picture of me to insult me," it is "annoying or distasteful humor," or just "it's a bad photo of me." Then the user is prompted to directly message the person who posted the photo to resolve the conflict interpersonally.

Those categories, of course, won't translate as well in other countries. Building on its research of what people are flagging, Facebook is working on creating new reporting options for different markets. Now in India along with its usual community standard violations, users can choose to flag photos with: "This insults my country, this disrespects my religion or beliefs," "this violates my privacy," and "this insults someone or something I care about" — a tweaked version of "this insults a celebrity," which wasn't getting the proper results. Facebook is continually changing the language and shifting the categories as it collects user feedback.

In some areas, such as Turkey and the Middle East, Facebook has a category of terrorism — differentiated from violence. "The one thing about terrorism," explains Brill, "is it is in eye of beholder. Some organizations are defined that way by some people, but not by all. Facebook doesn't want to label this versus that as terrorism. But we want to know that that is why someone is reporting it." Depending on your political views, a group could be seen as activists expressing political beliefs at a protest or engaging in terrorist activities.

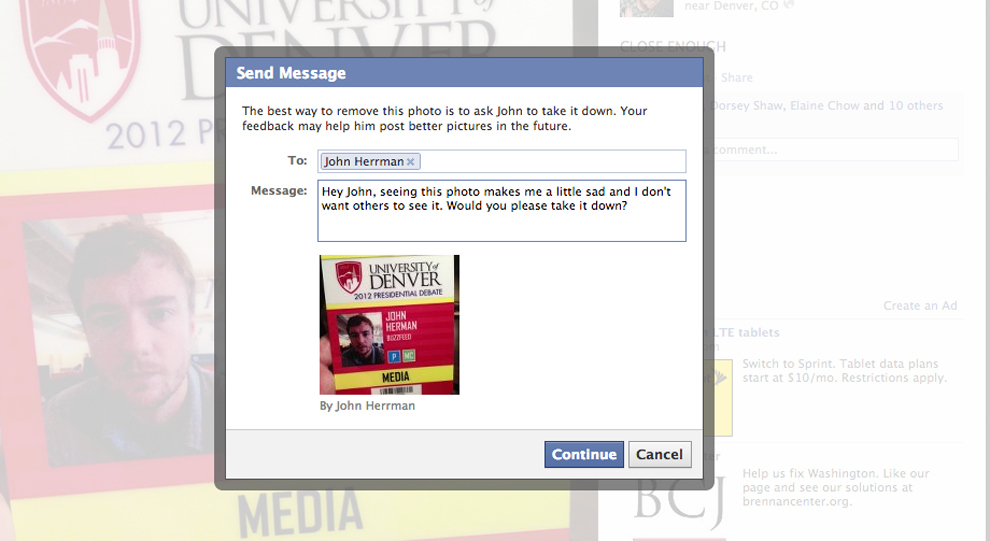

For the second element — sending the person who posted the photo a message — Facebook decided to craft the message itself. Yes, Facebook is telling you what to say to your friends when they do something you don't like. You can replace its suggested wording with your own — Arturo Bejar, who is leading the project, says Facebook prefers that — but Facebook found that when faced with an empty message box versus one with a note written by Facebook, the rate of sending the message shot up from 20 to 60 percent. Maybe people just can't find the words to say what they want to say. Facebook spent months tweaking the language. "Would you please take it down?" for example, has a higher response rate than "Would you mind taking it down?"

Facebook is now working to tailor the message to other countries. According to Facebook, it needs to be more direct and less polite for Israelis. "Take this down" will work better than "Would you please take this down." In Japan the challenge will be to get people to vocalize the complaint at all. In India, emotional messaging is tricky because it often escalates, even though the argument doesn't carry over into real life.

It's working: About 85 percent of the time, the poster either took down the offending photo or had a conversation with the reporter. Sixty percent of the people who were contacted about what they posted said they felt positive about the person who sent the request; 20 percent said they felt neutral. Mean girls don't always mean to be mean. And while you can still block someone, Facebook has hidden that option, making it slightly more difficult. Rates of blocking are down to 0.1 percent.

Even though users had to go through multiple steps and spent on average 19 versus 15 seconds reporting the problem, the completion rate amongst 13 to 14 year olds, whom they focused on, jumped from 77 to 80 percent. It went against the basic computer design mantra: keep things as simple and streamlined as possible. "It flies in the face everything we know," says Brill. "It changes the perspective on building a product."

When surveying 13 and 14 year olds — the youngest kids allowed on the site and the most vulnerable to cyber-bullying — researchers discovered that young teens thought reporting a photo meant authorities would be alerted. "They wanted Facebook to do something about it, but they weren't sure what that was," says Bejar. "They wanted to feel like having a conversation with someone on other end of computer really cared." For them, there's an extra feature that encourages them to send an email to a trusted adult. "It used to be impossible when you were being bullied to talk to the bully," says Bejar. "We want to encourage the interaction to stop before it escalates."

The engineers and social scientists are thinking about possibilities for future research and applications: resolving chronic conflicts between people, branching out to other subcultures in the United States, and encouraging dialogue between people who keep hiding posts that they don't agree with — something which increased during the election.

"There is something universal all over the world that we have touched on with these basic principals," says Bejar. "We have so much work to do."