PITTSBURGH — Before Oct. 27, 2018, Joyce Fienberg and her young great-niece were best friends.

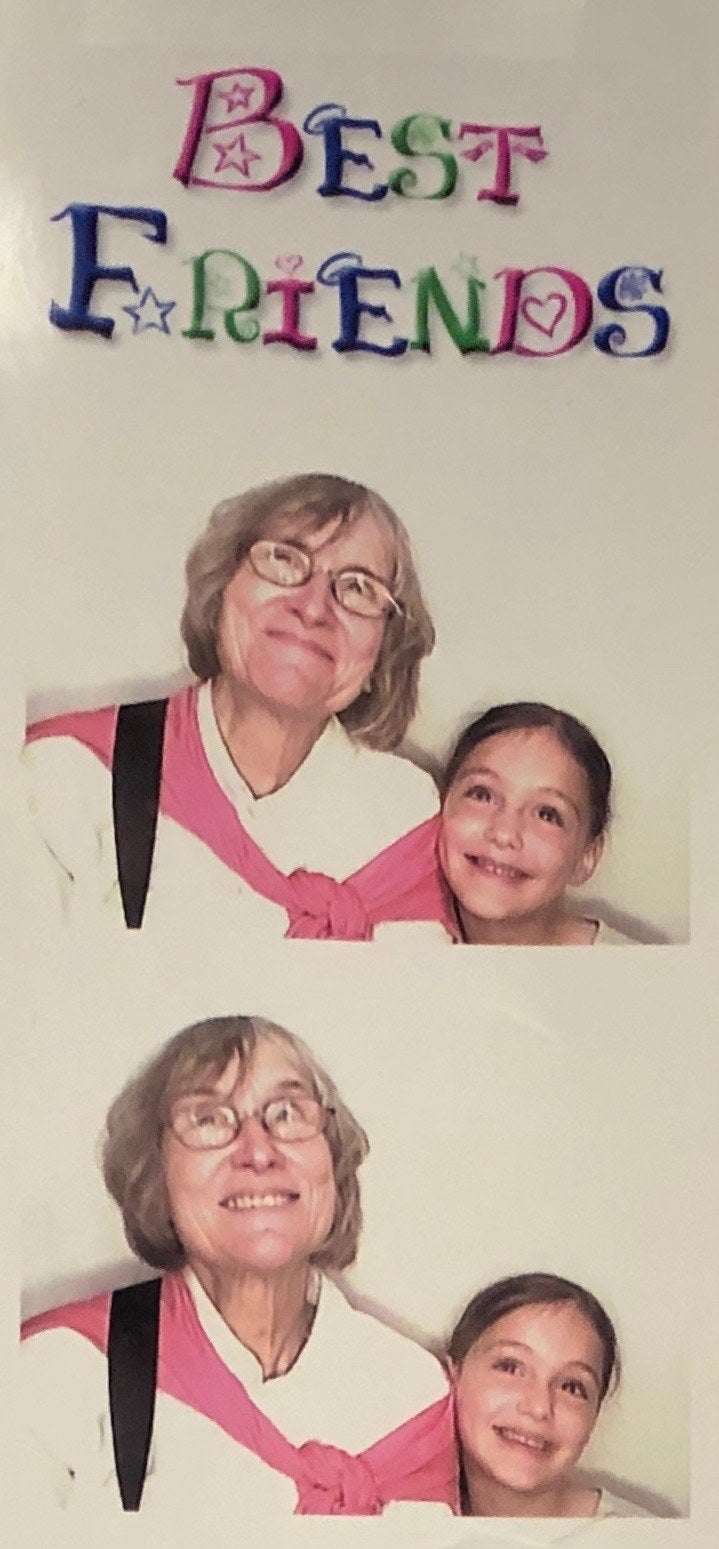

They did puzzles, played mini golf, and went to the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh together. There were Shabbat dinners every Friday night and sleepovers when the girl’s parents were out of town. Some might not think of the relationship between a great-aunt and a great-niece as particularly close, but the two had a unique bond. “My daughter didn’t have any grandparents in Pittsburgh, so she really treated my aunt as if she was her grandmother,” the now–7-year-old’s mother told BuzzFeed News. “We had this thing on my fridge that says ‘Best Friends,’ and it’s a picture of my daughter and my aunt together.”

When Fienberg, 75, was killed at the Tree of Life synagogue in the city’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood last year by a suspect who had railed against Jews online, her entire family was left devastated. But her great-niece, in particular, seemed broken, unsure even how to comprehend her pain and the magnitude of loss.

“She couldn’t express herself,” the mother said of her child, who was 6 at the time of the shooting. “My daughter kept wetting herself — it was like she was going back in stages of normal maturity.” (BuzzFeed News agreed not to name the mother or daughter to protect their privacy and security.)

The family had moved to Cleveland just months before, so after the shooting they drove back to Pittsburgh to sit shiva, the Jewish mourning ritual. When they arrived, the young girl refused to go anywhere near her great-aunt’s house or to synagogue. “She was really traumatized,” her mother said. “During school, she stopped paying attention, and her teachers were concerned about how she was doing. I spoke to her about it, and … she said, ‘Do you ever have daydreams? ... I have dreams during the day about bad guys shooting people.’ I was like, Oh my god.”

The young girl is just one of countless children in Pittsburgh and beyond who, at a formative time in their lives, have been traumatized by a massacre designed to make them afraid to be Jewish. While the 11 victims of the Tree of Life shooting were older Jews — the youngest, David Rosenthal, was 54; the oldest, Rose Mallinger, was 97 — young Jews have also been deeply scarred as they mourn both loved ones and strangers. On Sunday, the country paused to mark a year since the tragedy — but these children have been haunted by it every single day. For them, the one-year commemoration was just the first of many that lie ahead.

“I’m nervous for her — what it’s going to be like, how she’s going to deal with this throughout her life,” her mother said. “This will affect her her whole life — it’s not something that will just go away.”

Squirrel Hill is a community with a wound that will never completely heal. One year on, the Tree of Life synagogue remains empty. Plans have been made to reopen it as a Jewish community space, and the city’s Holocaust Center is set to move in. But for now, the doors remain shut. Visible inside are 11 wooden Stars of David painted with each of the victims’ names — memorials that were once outside but have since been moved indoors.

Now, more than 100 works of art — including some by young students from Parkland, Columbine, and Newtown — are on display outside the synagogue, sharing messages of sympathy and solidarity from young people who themselves are well acquainted with the pain of gun violence. One piece by a Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School student contains an English-translated lyric from the K-pop group BTS: “The morning will come again because no darkness, no season, can last forever.”

Growing up in the US, Pittsburgh’s Jewish teens already had reason to live in fear of the school shootings that have killed far too many people their age. But now, they also live in fear of anti-Semitic violence, which has risen to troubling levels nationwide.

Months before the tragedy at the synagogue where her family once belonged, Kaylee Werner, 16, had been grappling with grief from another shooting. In the attack at Parkland’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Kaylee lost Jaime Guttenberg, a family friend, and Alex Schachter, a distant cousin.

Now, when her mind wanders in class, she imagines what would happen if a shooter walked in the door. How would she try to escape? Could she make it through that window? Would she have a chance to survive, or would she be dead before she even knew it was happening?

“We had a bomb threat at our school on Thursday,” she said with an air of resignation. “It was canceled, [but] to me, it hit me differently than most of my friends. My friends called it ‘Bomb Day’ and laughed and went out to get lunch together. But I was like, ‘Sorry guys, I can’t do it today.’”

After Parkland, Kaylee turned her anguish into activism, joining protests, organizing a letter-writing campaign, and starting a nonprofit called Gunday Monday. She met with her elected officials, including Keith Rothfus, then a member of Congress, but she found their encounter unproductive. “At the end of the meeting, I went up to him, looked him in the eye, and said, ‘If another person dies by an AR-15 in our community, it’s your fault because you did nothing to stop it, and I’m giving you that warning now,’” Kaylee said.

Then, Oct. 27 came.

“He had the audacity to come to our vigil,” Kaylee said. (Rothfus, a Republican, lost his seat to a Democrat in the 2018 midterm elections. He did not respond to a request for comment from BuzzFeed News.)

Everything changed for Kaylee after that day. She missed a lot of school, had difficulty connecting with her non-Jewish friends, and found herself suddenly bursting into tears. She has since been diagnosed with PTSD. She’s lost count of the number of therapists she’s seen.

Now, she finds some peace by rowing with her school’s crew team as the sun rises and sets on the Allegheny River. “The blades clicking all together is so meditative for me,” she said. “That’s the only way I feel sane.”

“I feel like it’s been a long journey to get to where I am now, and there’s still a long way to go,” Kaylee said. “I feel way better standing here today than standing here last year.”

On Saturday night, Kaylee helped lead a service for Havdalah, the end of Shabbat, as dozens of Jewish high schoolers sat in circles on the carpet of Beth Shalom, a local synagogue where all three Tree of Life congregations held their first Shabbat services after the attack last year. There, the teens opened up about the ways this past year has changed them — how much closer they now feel to their Jewish friends, how scared they are to go to synagogue, how sometimes they find themselves crying for no reason.

Trying to make the teens feel safe is something Lindsay Migdal spends a lot of time thinking about. Migdal is the Pittsburgh-area regional director of BBYO, a Jewish youth group that Kaylee and many of the teens at the Havdalah service are members of.

A few weeks after the shooting last year, the young Pittsburgh Jews attended a weekend-long retreat. At the time, Migdal wondered whether they should reschedule it. The event ultimately went ahead, but with some additions: Migdal hired security and on-site social workers who were available 24/7 and brought in therapy dogs.

“I wanted to make sure when they walked into a room, they didn’t feel like they had to look for the exits, which is something they talk about,” Migdal said. “I wanted to make sure they could focus on having fun and being Jewish in a safe setting — not being afraid.”

In Beth Shalom on Saturday, the teens, wearing matching white T-shirts bearing the words “Remember. Repair. Together,” all stood to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish prayer as one. Usually, only those in a congregation who are in mourning stand and recite the Hebrew prayer. On this night, it was everyone.

Later, they wrapped their arms around one another and sang along to Matisyahu’s 2009 song “One Day.” “One day this all will change,” they sang. “Treat people the same / Stop with the violence / Down with the hate.”

That such a vile and deadly anti-Semitic attack could occur in Squirrel Hill was particularly shattering to those who live in the neighborhood, which serves as a haven to a uniquely strong and close-knit Jewish community. According to a 2017 study, some 26% of Pittsburgh’s Jews live in Squirrel Hill, which is home to more than 20 synagogues, three Jewish day schools, and a variety of kosher restaurants and bakeries. Almost half of all the city’s Jewish children live in the neighborhood.

Nestled in Squirrel Hill are several Jewish community organizations that offer mental health services, which many young Jews have sought out since the shooting. Angelica Joy Miskanin, a trauma therapist at the local Jewish Family and Community Services (JFCS) office, has seen a wide range in how the youngest Jewish residents are coping a year after the tragedy. Some are no longer experiencing trauma symptoms, she said, but others are still very much struggling.

“Some kiddos are and have been having a really difficult time, struggling with growing up in an age of school shootings being more the norm,” Miskanin said, “and in addition to that, living in this community and having some relationship with the shooting just by being here.”

She added: “They’re also going through active shooter drills on a regular basis in their school settings, and that’s a reality as well, so we’ll talk about the feelings that come up around that.”

Miskanin previously worked at JFCS for four years, but left for another job in 2010. She returned after the shooting last year when a lot of people began seeking professional help. “It seemed really evident right away that the need was there,” she said. “My caseload was pretty full within a month or so of being here.”

In the children she’s seen in the community, Miskanin said she’s observed a variety of symptoms, including hypervigilance, anxiety about the thought of loved ones being killed, and a loss of interest in activities they once enjoyed. Many also have physical symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping and stomach issues.

“For many people, it has shifted their story,” Miskanin said.

Pittsburgh’s Resiliency Center, also known as the 10.27 Healing Partnership, is a federally funded space that assists all who were impacted by what they refer to as “hate-induced trauma” as a result of the attack. The center just opened earlier this month, and director Maggie Feinstein said she wants it to be a healing place.

“Teens were coming from school having intense conversations, intense feelings,” Feinstein said. “So, I hope this can be a space where kids can come and speak with each other, feel free to say what they’re angry, scared, or sad about, all those harder emotions.”

While the center is available to people of all ages, Feinstein is particularly concerned about Pittsburgh’s teens. Unlike younger kids, they are active on social media — where they can access boundless information about the attack on their community. But unlike adults, their brains are still developing and acutely vulnerable to permanent damage from PTSD. “If they're consuming media on their own — like the teens who are on social media and who can find what they want — you have to then be ready to answer the questions they have,” Feinstein said.

As the youngest members of the community grow up and hit new developmental stages, Feinstein expects more and more of them to seek help eventually. Young children don’t understand the concept of permanency until around 5 or 6, she noted: “So they may have known what happened, but once they have the realization that those lives that were lost will never be back and they don’t live anymore, they may have a whole different experience.”

On Friday night, ahead of the weekend’s solemn events, Pittsburgh’s Jews gathered around their dinner tables to observe Shabbat. Over a cozy dinner in their Squirrel Hill home, David and Rebecca Knoll and their three children discussed the year that had passed. Between bites of spaghetti and meatballs, their 8-year-old daughter chatted about her memories of hiding under a table, and how all the kids she was with were “freaking out.” Their 11-year-old son calmly asked questions about the shooter’s upcoming trial.

The family, whose children are fifth-generation Pittsburghers, were at their synagogue attending a bar mitzvah when gunfire rang out a mile down the road at Tree of Life. They initiated their security protocol, and David Knoll put his body in front of the door to the building to block it. “I remember clearly — because something like that is seared into your brain — [my kids] asked, ‘Is the shooter coming here to us?’” Knoll recalled. “When your kids have to ask that, it’s a sickening question. No kid should ever have to ask, ‘Is someone coming here to kill us?’”

All three children coped differently in the immediate aftermath, according to their mother. “My two older ones were pretty visibly shaken,” Rebecca Knoll said. “They were pretty rattled.”

Because the family is Shabbat observant, and the shooting took place on a Saturday, they could not call their loved ones or watch the news for many hours. When Shabbat finally ended at sundown, the 11-year-old wanted to consume all the news he could, whereas their 10-year-old son called up every single one of their relatives.

But a year later, sitting around the Shabbat table, the children seem much more at ease. “In terms of my kids, the initial weekend was pretty traumatic in terms of it was something they never could’ve expected,” David Knoll said. “Things come up every now and then, but they’re doing great now.”

Miskanin, the JFCS therapist, said the way children are responding to the tragedy a year later is varying widely. “My experience from working with kiddos is certainly that they’re incredibly resilient,” Miskanin said. “Some kiddos are at this point remembering and many of them trying to find ways to honor the commemoration, but some are not reporting a lot of heightened symptoms. Many are feeling pretty well.”

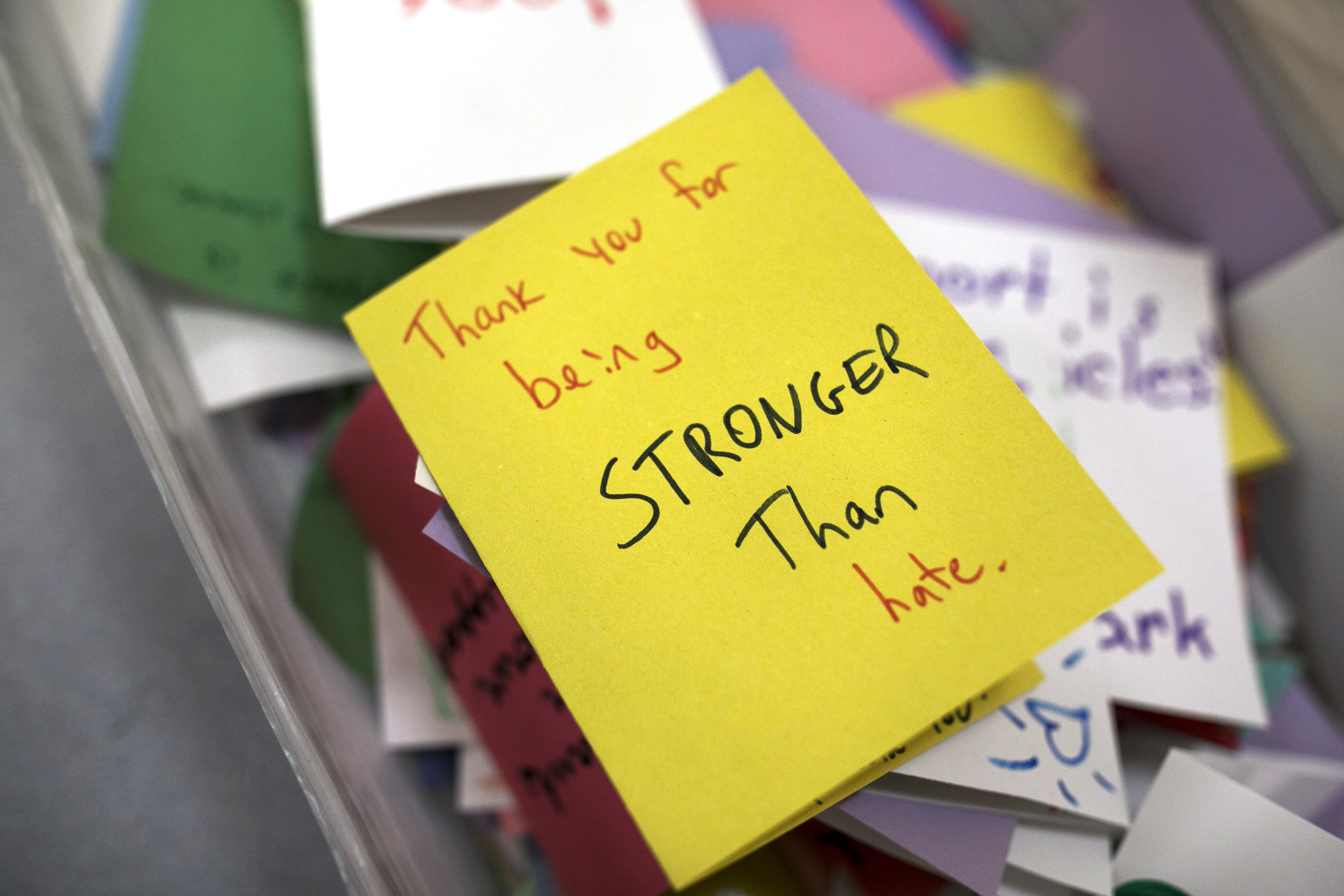

On Sunday, exactly one year after the shooting, the people of Squirrel Hill gathered to remember the 11 members of their community who died. Flowers, notes, and candles were placed around the Tree of Life synagogue. A plate-sized rock — which Jews traditionally place on the graves of their loved ones — was left near the building, painted with the words “stronger than hate” and an image of a squirrel.

More than 30 community service events were held that day, from cleaning up Jewish cemeteries to making heart-shaped pillows for refugee families.

Joyce Fienberg’s 7-year-old great-niece was among those in attendance, using crayons to make get-well cards for people staying at nearby hospitals.

The young girl still did not want to talk about the shooting. When her great-aunt’s name was brought up, she looked down and her voice lowered to just above a whisper. She twisted her hands and tugged at the pink and white stripes on her dress, which was emblazoned with a pink sequined heart. She vigorously smoothed it, as if she could physically wipe away the painful memories.

“She was a good person in our family,” the little girl said of her great-aunt. “She would help us a lot.”

Her mother said the girl recently told her she was worried about forgetting the great-aunt, who was so important to her: “She said, ‘I don’t want to forget her, but I want to forget how it happened.'"

Since the shooting, the young girl has developed an acute fear of death. When a classmate jokingly said “I’m gonna kill you” to her once, the girl came home crying, afraid she would literally be killed.

In addition to doing everything she can to help her daughter cope with the trauma, the girl’s mother has pain of her own to navigate — compounded with guilt about whether she’s doing enough or doing the right things to help her child. “That week right after, I was going through so much that I couldn’t give her the attention she needed, and I feel like I messed up that week,” she said. “Like, maybe if I would’ve given her more time and been more helpful that week, then maybe the rest of the aftermath would be better.”

The mother still has dreams about Aunt Joyce, sometimes just running into her in the grocery store as she sleeps. She, too, has seen a grief counselor.

“It’s so hard — everyone grieves differently, and now they have all these ideas that grieving and talking about it make you feel better,” she said. “The question is, how much do you push, and how much do you not push? … I don’t want to push her and have all these negative thoughts come up for her, but I don’t want her to push them down, either. I don’t know what the healthiest thing to do is.”

The mother and daughter stayed close to each other on Sunday, coloring the cards together. In her arms, the mother cradled her 4-month-old daughter Joy — her name a tribute to the great-aunt she will never get to meet.

In some ways, it was a difficult weekend for the family. But at the same time, the grief is something they’ve experienced — together — every day for a year.

“I knew it was going to be a hard weekend, but I remember her every day,” said the mother. “It’s this one-year commemoration — but for me, every day is without Auntie Joyce. So, it happens to be a year, but tomorrow is going to be a year and one day.” ●