A few weeks ago, I was listening to Spotify when an ad came on featuring a vaguely familiar male voice that made my ears perk up. It was a bit higher-pitched for a man’s, and every syllable uttered felt masterfully deliberate in its delivery, each Brooklyn-accent-tinged word exaggerated with perfect-length pauses. He was reciting a stand-up routine about shooting a moose, where his aim was so poor that he didn’t end up killing the animal, only knocking it unconscious. The audience enveloped him in laughter as he described driving through the Holland Tunnel while a moose tied to his fender started to slowly wake up, the true core of the joke lying in the fact that this man was too gentle, too much of a klutz to truly hurt anything.

As the ad neared its end, I saw that it came from an album of Woody Allen’s early stand-up years, and I felt a strange guilt for being drawn to his work before I realized it was his. Ever since his estranged daughter Dylan Farrow published an explosive op-ed in the New York Times last year alleging that Allen had sexually abused her as a child, I have been unsure of how to move on in life without him, especially since people I respect and care about seem to be able to overlook this aspect of his life. My parents, for instance, believe that an artist’s personal life should not influence how we perceive their art, that such judgment is not up to us to make and only stifles creativity. Denouncing Allen for his behavior makes me feel like the closed-minded type of person I’ve always feared becoming.

Woody Allen's films raised me. I was introduced to him at an early age, and he cut through the noise of a tumultuous home with surprisingly clarity. My parents went through unimaginable hardship immigrating to the U.S. from Ukraine, the stress of overcoming poverty and learning a new language accumulating over the years and making our three-person family feel as though it was being tugged at from every corner. The American dream was very much there, but it was accented with anxiety and deep feelings of entrapment, and every conflict between us would, at some point, feel hopelessly insurmountable.

A neurotic unit, we drifted toward Woody Allen as if he were a lighthouse. When we turned on Small Time Crooks or The Curse of the Jade Scorpion or Deconstructing Harry, we were mystified by his ability to be nervous and existential without ever being dramatic. He was boundlessly intelligent and could experience a full spectrum of emotion, but he never resorted to screaming or cursing or knocking down objects out of frustration. He used his words, and, as seen in Annie Hall when he creatively insulted a pretentious moviegoer in his mind, his judgments could be harsh. But, in his early films, the problems of his characters could somehow be tucked away peacefully without feeling too easy. His work was, in some ways, the perfect lens through which to view life — he could offer a joyful escape while also making you actively think about life and death and the infinite strangeness of people.

In 2009, during my freshman year at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts (coincidentally Allen’s alma mater before he dropped out), I had an essay professor who was particularly fascinated by him and introduced us to films like Stardust Memories and Another Woman, providing us with essays to read about Bergman and Fellini, who were great influences for Allen. I discovered the darkness of Match Point and the unbridled sensuality of Vicky Cristina Barcelona — admiring him even more than I had growing up. I learned that he was deeply agoraphobic, ate only what was healthy, and produced a film a year, never letting a bad review set him back.

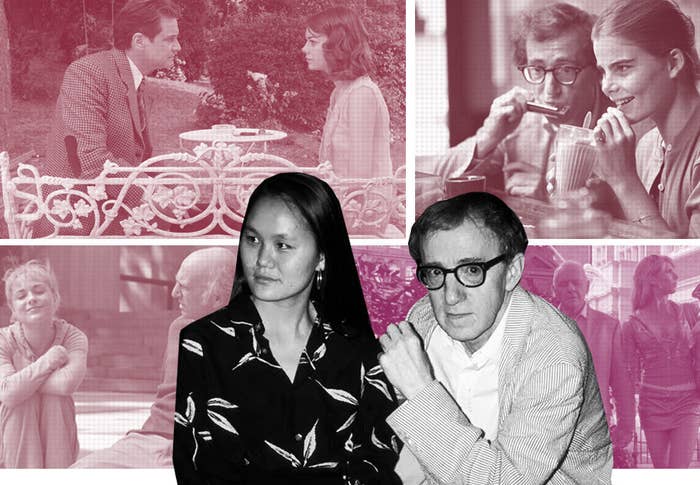

During the course, we covered writing personal essays, and my professor chose a chapter from Mia Farrow’s autobiography where she describes the exact moment she discovered a nude photo of Soon-Yi. My professor seemed to present this as just another odd tidbit about Allen’s personal life, akin to his weekly jazz gigs at the Carlyle Hotel, but reading about Mia’s reaction in the split second where her life was irrevocably shifted still sits in my mind like a grotesque photograph. Until that point, I had heard of Soon-Yi only in whispers. They had a big age difference. She had been his stepdaughter. And now she was his wife. It had upset people when it happened. It was certainly never anything discussed among my family, and by the first time I had watched a Woody Allen movie, it was over a decade later, in the 2000s, and the controversy had faded.

Once, I was talking to one of my NYU classmates about Allen and she said, “Ew, I hate Woody Allen. He’s such a creep.” At the time, I saw her as annoyingly pretentious, as if she was looking to have an unpopular opinion. Even though I was always a bit bothered by the fictional relationship in Manhattan between Allen’s 42-year-old protagonist Isaac and 17-year-old Tracy (or, more specifically, the fact that it was never once acknowledged as weird in the film), I didn't think that alone was a reason to dislike Allen or link the film to his personal life. In fact, while his getting together with Soon-Yi was referred to as a scandal by the public, it also seemed to teenage me like it could be an unconventional love story, where a rock-bottom moment led to a long-awaited breakup and then the freedom for Woody Allen and Soon-Yi Previn to wed and be together to this day. And because they stayed together, I didn’t think it was up to me to relate or “get it” — the proof that it was supposedly OK was there in the happy red carpet photos and documentary appearances. Sometimes I did wonder about the marriage — if Soon-Yi hypothetically did want a divorce, where could she realistically go? Since she initially saw Allen as a father figure, couldn’t that have had a psychological impact on her? — but I never contemplated not watching his films anymore.

After my freshman year, I met all kinds of people. I worked as a sexual health advocate on campus, and a big part of that was talking about rape culture and sexual assault prevention. I got into conversations about child sexual abuse and met several survivors. I saw my friends still struggle a decade after their respective attacks to adjust to normal life, and I kept seeing how victim-blaming played a role — how sometimes their own parents wouldn’t believe them. I never wanted to be the person who doubted them, who made the already impossible burden of dealing with sexual abuse even heavier.

Dylan’s New York Times article makes me feel vehement emotions I don’t know what to do with. I’ve replayed her words in my head a maddening amount of times and thought about what I would do if I were Mia, what I would do the moment I was told this story and then had to wait for Allen to walk through the front door, what I would do if I then had to see him become one of the most iconic American filmmakers of all time while watching my child fight just to not disappear into herself. Every article I read that prods Dylan’s story for loopholes or accuses Mia of planting these memories into Dylan’s 7-year-old head blurs my vision and takes me to a dark place where I am reminded that, if you’re a woman who has been harmed by a man, you will be doubted, sometimes in the same breath as you opened up.

My parents don’t like actually going to the movies that much, but about once a year they drive to the independent theater 40 minutes from our house to catch Allen’s latest film. They bring up his films to me with the same level of excitement as before, and I nod and smile politely because it’s not an argument I want to have in the walls of my family home. His films will always have an emotional association for me — for us — and I guess I don’t want to tamper with that. Mostly, though, Woody Allen represents and reminds me of one of the things I love most about my parents — the fact that they introduced me to artistic, clever, complicated movies from an early age. In my memories, Woody Allen movies are as prominent as the weekend art museum trips and the Led Zeppelin listening sessions. It all ended up teaching me to never be a passive recipient of information, which, in some cases, means wholeheartedly disagreeing with the people I respect the most in the world about a filmmaker we all love and have loved.

Still, I don’t know what it means to truly omit Woody Allen from my life. In a college thesis script I’ve been revising, I have a cartoon character that I based directly off of Allen. He's described as a white dwarf star who is always soft-spoken and stressed, mostly because he’s a fragile, pressured ball of hot gas. In a web series script I wrote recently, I realized, reading it back later, that I had written a moment that unintentionally paralleled Alvy Singer and Annie Hall’s iconic first kiss. My personal writing projects are littered with these subconscious hat tips, ones that I don’t always so willingly want to take back.

I will never buy another ticket to a Woody Allen movie, but it is my own choice that I’ve tucked away inside me. Sometimes, I reminisce on the summer of my sophomore year in college, when I was at the peak of my depression from a relationship I was too cowardly to leave and I saw Midnight in Paris with a friend and felt a glow return to my body. This was the best Woody Allen film I had seen in so long, and it made me excited for the possibility of more movies like this. It was the most simply and brilliantly imaginative piece of art I had seen in so long at that point, and it was as if it recharged me as a person. I remember not wanting to leave the blissfully romantic world Allen had created. We lingered in our seats for a while through the credits, watching everyone else slowly exit the theater. Eventually, we looked at each other, deciding it was finally time to go.