When Nicole S. woke up after giving birth at a hospital in southern Germany just over a decade ago, the midwife told her that she was now the mother of a baby boy. The new parents decided to name the child Jonas. The next day, the senior physician called Nicole S.’s husband with a correction. “Actually,” the physician said, “the child is more of a girl.”

Doctors visiting Nicole S.’s room recommended cosmetic surgery. “They said it’s nothing to worry about, nobody will see it ever again,” Nicole S. told BuzzFeed News. At this point, she and her husband were worried about their child and left feeling alone, Nicole S. recalled. And they were up against a deadline: Their newborn’s gender needed to be reported to the registrar’s office.

For more on this story, watch the new BuzzFeed News show Follow This on Netflix.

“There was so little information. What’s the right thing to do here?” asked Nicole S., in a recent interview with BuzzFeed News.

“I have the impression that there are no well-trained personnel for these instances,” her husband said.

Nicole S.’s intersex child is 11 years old now. Melina, who was born with a penis and a vagina, says “I am both,” when speaking with her parents and siblings. Shortly after she was born, doctors diagnosed her with “true hermaphroditism,” which in the US is a medical term that’s no longer regularly in use.

Nicole S. and Melina are pseudonyms, as the mother wishes to remain anonymous, to protect her daughter from the public. “The subject is taboo, even today,” Nicole S. said.

(Despite multiple telephone and email requests to various associations and people who have dealt with the issue, only the S. family has been willing to speak with BuzzFeed News.)

Around one in every 2,000 children is born intersex, according to the National Institutes of Health, the largest health authority in the US. Another estimate places the figure much higher, at up to 1.7% worldwide. It’s hard to pin down a number because intersexuality, like color, is a spectrum: It depends on which biological markers are used to determine where one sex ends and the other begins.

“The subject is taboo, even today.”

People are classified as intersex if they are neither clearly male nor female. This may be because they were born with both a penis and a vagina, or because their body doesn’t recognize certain sex hormones. For decades, doctors have often reacted with largely uncontrolled and controversial operations, and hormone treatments in order to make infants’ genitals and sex organs “more normal.” It’s a practice that continues partly to this day in Germany.

Attorneys, with focuses as diverse as human rights and science, consider these surgeries to be (at times grievous) bodily harm. But there are virtually never any legal consequences for the doctors who perform them. The largest interest group for intersex individuals in Germany, Intersexuelle Menschen e.V., offers free consultations to affected families around the country, but these services are rarely used. Many doctors and midwives are unaware of the most recent medical guidelines on the matter. As a result dozens, or even hundreds, of genital operations are performed on intersex children every year — some of which, according to research conducted by BuzzFeed News, are clear violations of German medical guidelines. And there is barely any political interest in the topic, in Germany or abroad.

BuzzFeed News has spoken with doctors, professional associations, affected individuals, and attorneys. While the medical world wants to cure people with differences of sex development, also known as DSD and formerly called disorders of sex development, people who are diagnosed with such often do not see their condition as a disease. And in current medical practice, there is an intermingling of social and medical ideas about what a “healthy” sex actually is.

When Melina was first born, the hospital’s chief physician advised Nicole S. and her husband to raise the child as a girl, but to postpone an operation. She gave them the address of an intersex self-help group. The parents read up online and made an appointment at a special clinic in Lübeck, northern Germany, meeting with renowned physician Olaf Hiort, who runs the hormone center there and specializes in intersex patients.

There, the doctors performed an ultrasound where they learned Melina had an ovary on one side, a testicle on the other, and a womb. But also, more importantly, she was healthy. The parents opted to raise the child as a girl, only openly speaking with their close friends and family members about Melina’s intersexuality.

“Unfortunately our society is still so binary-driven.”

Yet Nicole S. is now uncertain whether they made the right choice. “I don’t know if it’s good that Melina’s gender role is so defined now, even though she can change it whenever she wants.” She wishes she had more time after giving birth to have made a decision. “At the time I didn’t think it was right to raise our daughter entirely intersex and to tell everyone about it. I was just afraid of her being ostracized.” When Nicole S. eventually told Melina’s kindergarten teacher and later the principal about her daughter’s intersexuality, neither of them had ever heard of it.

“Unfortunately our society is still so binary-driven,” Nicole S. said.

“Only over time do you learn that it’s not just black and white,” her husband agreed.

The list of resulting complications is long for parents who opted for a surgery: pain, decreased sexual enjoyment and sensation, infertility, lifelong hormone therapy, inflammation, depression, risk of suicide, shattered family relationships. And there are many cases of intersexual adults who, as children, were surgically “turned into” a boy or girl but who now feel as though their gender identity doesn’t align with the bodies they were surgically given.

One person who wishes they had never had the surgery as a child is Maxi Bauermeister, who was born at a time when Germany was still divided into two separate states. “In my opinion, I was forcibly castrated,” Maxi said in an interview with BuzzFeed News.

When Maxi’s mother, Christiane, was in the advanced stages of her pregnancy, she went in for an ultrasound, thinking she was going to have a boy. “The penis isn’t presenting,” the doctor told her. Christiane did not think anything of it at the time, thinking the penis would develop. On the third day following the birth, the doctors came to her bedside and said, “We cannot determine the sex of the child. It doesn’t have a penis. It would be best if you raise the child as a girl.”

“I was incredibly shocked and thought, I can’t just turn a boy into a girl; I’m not God almighty, after all,” Christiane told BuzzFeed News.

She discussed the issue with the child’s father — felt disconcerted and helpless. It was 1984, and the word “intersex” was unheard of. There was no information on the subject except for the doctors’ advice: “Turn the child into a girl.”

The parents at first decided against a surgery; the child’s sex wasn’t immediately recorded on their birth certificate. When Christiane traveled to visit her family in south Germany, she smuggled the child onto the airplane in a bag because they did not have a passport. Christiane went to various specialists, all of whom told her the same thing: Only as a girl will the child be able to lead a happy life.

When Maxi turned 2, Christiane agreed to an operation where the child’s testicles were removed from the abdomen. The child was sterilized for life as a result, Christiane told BuzzFeed News. (Although there are no medical records to prove Maxi would have been fertile, there are many cases where intersex children have the potential for fertility.) A hole was then surgically created to act as an artificial vagina.

As late as recent decades, intersex children’s vaginas were regularly penetrated with a “bougie,” an instrument used to ensure that the artificially created hole would not close again. The children’s so-called neo-vaginas were regularly expanded with candle-shaped metal rods of various sizes. There’s no evidence the highly criticized practice is still used today; when Maxi was born, they were spared.

Much has changed since then. Malta banned “normalizing” surgeries on intersex children in 2015, making it the first and still only country worldwide to mandate this by law. Several new medical guidelines were published in recent years, including in 2006 and specifically in Germany in 2016. “No medical or psychological intervention will alter the state of ambiguity, per se,” reads the current German guideline from 2016. Operations must now be less invasive and more infrequent. And then, on Tuesday, Aug. 28, the California State Legislature passed a resolution denouncing “corrective” surgeries on intersex children.

“We are uncertain if, and to what extent, the guidelines published by the scientific medical societies in 2016 are adhered to,” wrote the German Medical Association in an email to BuzzFeed News. The guidelines are not legally binding, and there’s no oversight mechanism to determine whether they are read by doctors or medical personnel, such as midwives.

A study by Humboldt University of Berlin shows that around 1,700 genital operations are still performed on intersex children every year. The number of operations on children diagnosed as intersex has barely decreased since 2005.

“It’s incomprehensible to me that society and the government are standing idly by while genital mutilations are being performed on intersex children in Germany day after day,” Lucie Veith, one of the most well-known intersex activists in Germany and a member of the association Intersexuelle Menschen e.V., said during a phone interview.

Susanne Krege, director of the Urological Clinic in Essen, has a different view. “The ... accusation that we perform mutilations, I wouldn’t put it like that. It certainly was that way 20, 30 years ago, but nowadays we actually work with micro-instruments and magnifying spectacles, allowing us to perform very good reconstructive surgeries to male and female,” Krege told BuzzFeed News over the phone.

Doctors and activists have yet to agree on the question of when surgery is necessary for intersex children, given different understandings of where intersexuality begins.

Doctors and activists have yet to agree on the question of when surgery is necessary for intersex children.

Doctors frequently argue that corrections are necessary if a child will clearly develop into a boy or girl, yet the sex organs deviate from the norm or in terms of function. For example, when the hole of a penis does not end at the tip, but instead somewhere else, as is the case in about 1 in 300 newborn boys. Or when a girl’s clitoris is unusually large, which is sometimes associated with medical complications of the urethra.

They’re joined by a parent and patient initiative in Germany — called the CAH Parents and Patients Initiative — that advocates on behalf of people with a particularly common diagnosis called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). The initiative considers early genital surgery to be the correct course of action and a necessity, rather than cosmetic. The young women in the group meetings “are very satisfied with the results of operations,” the initiative wrote in a statement in the 2016 guidelines.

“These are cases of genital cutting. In the event of an enlarged clitoris, if doctors and parents claim that the child is a girl, then a girl is having her genitals mutilated,” says activist Veith.

An inquiry from BuzzFeed News to Germany’s Federal Statistical Office shows that between 2010 and 2016, at least 55 children under the age of 9 underwent clitoris surgery — even though they had been diagnosed as intersex.

Another request from BuzzFeed News shows that between 2005 and 2016, more than 11,000 surgical interventions on intersex children took place. Among them were more than 500 plastic reconstructions of the penis — a particularly drastic intervention — although the guidelines since 2005 have called for caution.

In 2015, the German Medical Association wrote in a statement: “In newborns and infants, no effective consent to an intervention is possible.” Concerned minors have the “right to an open future,” the statement said, adding that there should be no “irreversible surgical procedures” unless it is medically necessary.

And in the same year, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights concluded that intersex individuals in the EU are being denied their human rights.

Given the pressure to adhere to the new standards, many doctors have begun avoiding the press when it comes to intersex issues — some because they do not follow the guidelines and fear punishment, while others are wary of wading publicly into such a controversial topic.

Hiort, who also chairs the international intersex doctor network DSDnet, was not willing to speak with BuzzFeed News, despite multiple written and telephone requests over the span of months. A spokesperson for the hospital where Hiort works who spoke to BuzzFeed News over the phone earlier this year says that Hiort has to protect the physicians in the network from the public, and that there have been bad experiences in the past.

Another doctor reached by BuzzFeed News, who is herself intersex and who has published multiple articles on the topic, wished neither to speak about nor be quoted on the matter.

Krege is one of the few who does. “We always just argue that the child is being harmed when they are operated on so early. But if we leave the child with an inconsistent sex, there are no studies of whether this doesn’t also cause harm,” says Krege. In fact, there are hardly any studies of how intersex children develop without hormonal or surgical treatment. But research from 2014 shows that intersex children who grow up nonbinary in terms of their gender identity are not automatically discriminated against.

If and when these operations should be performed is not the only point of contention — another matter is who is allowed to decide. “I find it questionable for parents to be able to represent their children in these cases,” says attorney Konstanze Plett, who has been working on this topic for decades.

Whenever an operation is later believed to have been incorrect or botched, there are almost never legal proceedings against doctors or hospitals. This is because there are questions surrounding who would file the suit, since the parents themselves consented to the operation. It would be difficult for them to be able to prove after the fact that they were not sufficiently informed. During criminal proceedings, the medical norms at the time of the operation as well as the respective prevalent social values and mores are taken into consideration. Also, if the children are old enough to be able to take hospitals and doctors to court, the statute of limitations has often lapsed or the files are no longer in the archives.

“What use are the best laws if the people that they’re supposed to protect can’t use them?”

At a November 2017 symposium in Berlin, medical historian Anette Grünewald said that there are frequently surgeries that are not medically necessary in children under 2 years old. “Those fall into the range of the enhancement surgery and are thereby cosmetic operations,” Grünewald said, adding that these surgeries are punishable according to the current legal situation, but the laws are not enforced.

“There are cases of bodily harm or grievous bodily harm,” Plett told BuzzFeed News, referring to clitoris reductions or cases like Maxi Bauermeister, where the testes were removed and the child was made infertile. “That would not only be an offense, but a crime — like female genital mutilation, according to a new law from 2013.”

“Awareness among doctors that you shouldn’t do that has really increased in recent years,” Dr. Krege of the Clinic of Urology in Essen told BuzzFeed News. “But it’s uncertain whether this awareness will actually reach the most rural areas. ... And then, of course, there are those colleagues who simply don’t want to accept that things aren’t done the way they once were. They don’t want to believe these arguments.” She declined to name anybody specifically.

Nicole S., the mother with the 11-year-old child, confirms this from her own experiences in self-help groups. She estimates that half of the children from the groups were operated on without there having been any medical necessity to do so.

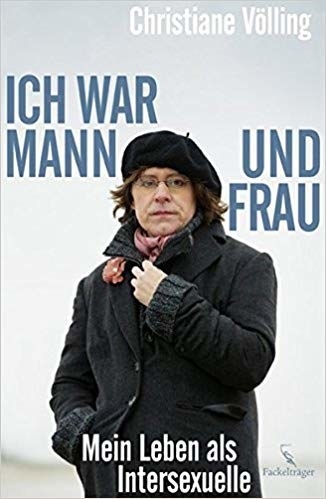

In 2009, Christiane Völling became the first and only intersex person to successfully sue a doctor in Germany, when she was awarded damages of 100,000 euros (around $117,000 under today’s exchange rate). In 1997, when she was 18 years old, Völling was forced to undergo an operation without her consent or any explanation, in which her uterus and ovaries were removed.

“That was a special case,” Plett said. “What use are the best laws if the people that they’re supposed to protect can’t use them?”

Every family in Germany with an intersex child is supposed to receive independent consultation before an operation, according to the guidelines from 2016. Yet there is only one provider of such consultations: Intersexuelle Menschen e.V. and its mere 33 volunteer advisers.

The association estimates that the free, nationwide consultation only reaches 15% of families with intersex children who undergo surgery, leaving the vast majority of them exclusively advised by doctors. This, they say, is insufficient.

“We have never been approached by a hospital in Hamburg for peer consultation,” Ursula Rosen, an adviser with Intersexuelle Menschen e.V., said during an expert hearing in the Senate of Hamburg in June 2018. This is remarkable because, between 2010 and 2015, multiple operations were performed in Hamburg on children who had been diagnosed as intersex. This is according to a large-scale inquiry of the Senate of Hamburg from July 2017.

“Not every hospital even knows about our association. And we weren’t taken seriously for a long time,” Rosen told BuzzFeed News.

There has been some movement on the issue politically inside Germany in recent years. Since 2013, it has been possible in Germany to omit one’s sex from a passport entirely. Maxi Bauermeister’s passport now bears an “X” in place of the “F” for “female” that was once there. But in 2017 the country’s Federal Constitutional Court declared that this is not sufficient. The court says that according to Germany’s General Personality Right (or the right to protection of one’s personal information and affairs), intersex persons have the right to a positive designation. For the first time in Germany, there will thus be a specific term for intersex individuals’ passports and birth certificates by the end of this year. That term will most likely be “Diverse.” Germany would be the first country in the European Union to take such a step.

Federal Minister of Justice Katarina Barley has announced multiple times her desire to ban operations on intersex children. As of yet there is no draft proposal for such a law.

“Quite a lot of people do not know what intersex is, even in this political landscape,” said Barley in an interview with BuzzFeed News. This was not necessarily ill will, she said, but often simple ignorance. “How to deal with minority issues that do not personally concern you, however, shows how strong a constitutional state and a democracy is,” said Barley. “If everyone thinks only of themselves, we become a society of egoists in which I do not want to live.”

“I wish I could just say, ‘this is my child, they are intersex, and they get to choose whether they want to play sports with the boys or the girls.’ That would be my dream,” Nicole S. said.

A few years ago, Melina told a friend she was playing with that she is intersex. The girls had taken their clothes off and the friend asked why Melina looked so different. After all, girls don’t have a penis. Melina’s father said, “Actually, some of them do.” That’s not true, said the friend, she read so in the newspaper. “But you can see for yourself, right in front of you,” answered Melina’s father. The friend took a look, and later asked her parents, “Can people buy that?” She wanted one, too. ●