Maisha Allums can't recall the precise moment she felt she lost control. It felt more like a series of moments. Each seemed strange to her at the time, but she had nothing to compare them to. Is this normal? she and her husband found themselves asking, until one day the question became a certainty: This can't be normal.

On July 1, 2014, Allums' mother Marlene Pinnock was pummeled on the side of Los Angeles's Interstate 10 by Daniel Andrew, an officer with the California Highway Patrol. A passerby posted a video of the beating to YouTube on July 2. News outlets picked up the story on July 4. Allums and her family lawyer, Caree Harper, began addressing press conferences on July 6.

This cycle of brutality and outrage has become dreadfully familiar to Americans in the past year and a half, but wasn't so much then. Michael Brown, whose death at the hands of a Missouri police officer ignited weeks of protests and propelled Black Lives Matter activism into the mainstream, was still alive during Pinnock's attack in L.A., after which she was hospitalized and Officer Andrew was put on administrative leave. Three months later, Pinnock settled with the county for $1.5 million, while the California Highway Patrol sent an investigation to the District Attorney's Office "outlining potentially serious charges" for Andrew, who had resigned. All signs pointed to justice. Until they didn't.

There were small things at first, Allums said: Before the settlement was reached, Harper, the lawyer, began referring to Pinnock as her cousin; Allums had to make appointments to see her mother; disagreements between Harper and Pinnock's family turned into shouting matches. Is this normal? Then came the very big thing: A federal judge threw Harper in jail for two days for not answering his questions about how she came to represent Pinnock and made her money off the case. This can't be normal.

Last week, the District Attorney's office announced Daniel Andrew would not be charged with a crime, saying it was "legal and necessary" for him to use force — to tackle, straddle, restrain, and repeatedly punch — "to protect not only his own life but also that of Ms. Pinnock." But as outrage over Pinnock's beating renews, only one thing is known about Pinnock herself: The 51-year-old transient woman with bipolar disorder is back to "square one," as her daughter says. Despite her new trust fund, she's spent recent months on the streets, off her medication, and in and out of hospitals. The only people whose lives have markedly changed are those caught up in the private-turned-public dispute over Pinnock's best interests — a tug-of-war fueled by money, ego, and complicated family ties, centered on a woman who calls nowhere home.

On one side: Allums and her husband — Pinnock's family. On the other: Pinnock's lawyer and friend — a woman who thinks she's family. Pinnock floats in and out of reach from both of them.

Allums, 38, was watching the news when she saw the clip for the first time. She had to do a double take, she said. "Is that my mom?"

She called the sheriff's department and local hospitals, looking for any information about the woman beaten on the 10. Robert Nobles, Allums' husband, described the day as exhausting. But just before midnight, Allums got a call from her great aunt — a woman she said she hadn't seen in at least 20 years. Her aunt also had Caree Harper, a Los Angeles–based attorney, on the line. Harper was known then for representing the family of a black Pasadena teenager who died in 2012 after being shot by police officers seven times.

The lawyer told Allums that at her aunt's request, she had learned where Pinnock was being held and could help the family. Harper came to Allums' South L.A. apartment that night. There, according to Allums and Nobles, she offered to take them to see Pinnock the next morning if — only if — Allums signed a retainer agreement hiring Harper as the family lawyer.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News late this summer, Allums explained why she signed it. "All I'm thinking," she said, hands folded evenly on her dining table, "is I want to see my mom and I'll deal with the rest later."

The next morning, Allums and Nobles visited Pinnock at Augustus Hawkins Mental Health Center, where Pinnock was on a 14-day hold for mental evaluation. When Pinnock talked about the beating during that time, she would only say was it wasn't her fault, her daughter and son-in-law recalled. "She said she thought it was the devil — she was trying to run away from the devil," Nobles said. Pinnock never explained how she ended up on the freeway, Nobles added, but they believed she was living at a “little encampment over there," near Interstate 10's La Brea exit.

When speaking about her mother, Allums deliberately uses the phrase "homeless by choice." "My mom was never 'homeless,'" she said. "She didn't want to stay here, or stay with her dad, or stay with her brother or sister or anything like that. … When she's off her meds, that's just kind of her deal."

Pinnock has been transient since at least 2001. She has bipolar disorder, which she self-medicates with alcohol, Allums said. While Allums and Nobles refer to Pinnock's alcoholism explicitly — saying it makes her "10 times worse" — Caree Harper speaks more generally about Pinnock's condition: "There are certain triggers," the lawyer said. "If not properly medicated, you can fall by the wayside. Sometimes [people with bipolar disorder] can have a secondary thing, like alcoholism or drug abuse." Harper has denied that Pinnock was drinking or on drugs at the time of her freeway beating.

Pinnock's two-week hospitalization following the attack was the first time she had consistently taken her medication in 15 years, Allums said. It was also during those two weeks that Harper and Pinnock became close; Harper began openly calling her client "Cousin P." "Early on we felt like we were kindreds," Harper explained. "We were kind of related."

As Harper and Pinnock grew closer, the lawyer's relationship with Pinnock’s daughter and son-in-law began to fissure. When Allums and Nobles needed to be at meetings or interviews or press conferences, Harper would pick them up in expensive cars — or send town cars and limos when she couldn't pick them up — they said. When reporters barraged with Allums with requests, Harper allegedly offered to put the couple up in a five-star hotel. They said no.

"We could tell that she was trying to overspend money, so we cut all that down. We cut all that crap," Nobles said. "We were kind of uncooperative with the way she wanted things."

At the hospital one day, Harper and Allums met with Pinnock's doctors to discuss Pinnock's progress and pending discharge. Allums told the hospital she didn't think her mother was ready to leave the facility.

"She was getting better as she was in there, but she still was sick. She had been off her meds for a long time," Allums said. "No one wanted to put her in there forever, but she needed to take that medicine, and she wouldn't have taken it if she was out."

When Harper disagreed with Allums in front of the doctors — arguing Pinnock was ready to be released — Allums left the meeting, she said. A few days later, there was another meeting; Harper allegedly told Allums she wasn't allowed to attend, at her mother's request. Pinnock had come to believe her daughter and son-in-law "wanted to lock her up for life," Allums said.

"And then," Nobles said, "She snuck her out." At that second meeting, the couple believes, doctors set a date for Pinnock's release, but Harper and Pinnock didn't tell Allums or Nobles that.

The following is largely Allums and Nobles' version of events — Harper has responded to some of the family's allegations, but not all of them.

Just before Harper "snuck" Pinnock out of the hospital, the couple had decided to fire her, they said. But for the three days following Pinnock's discharge, they didn't know where Pinnock was — again. Their lawyer wouldn't answer her phone, Allums said. When Pinnock finally called Allums and said she needed some time to herself, Allums was suspicious.

"My mom doesn't talk like that," Allums said. "She never tells me, 'Oh, I just need some time for myself to get it together.' So I knew that was Caree Harper talking."

Harper, who spoke to me in August on the patio of a restaurant on Venice Beach, arriving via bike, tells the story of Pinnock's discharge differently. On the day Pinnock was supposed to go home, Harper said, Allums and Nobles "would not accept her." So Harper put Pinnock up in a condo she paid for in Marina del Rey, the affluent yacht harbor neighborhood adjacent to Venice Beach. And on July 17, Harper filed a lawsuit on behalf of Pinnock against the officer, then a John Doe, along with the California Highway Patrol commissioner.

Sometime in August, Harper later said, Pinnock signed her own retainer agreement with Harper. And before Harper even met Allums and Nobles, Pinnock's aunt Brenda Hall-Woods — also called Alice, the woman who initially sought out Harper's help — had apparently signed one, too. What this meant to Allums and Nobles was that they didn't have the power to fire Harper anymore. Before, they only felt like they were losing control of their mother's case; now they knew they were. The couple was allowed to visit Pinnock's condo eventually, but they said they were never permitted to be alone with her.

"I had to call to make an appointment with her to see my mom," Allums said. "I didn't even know lawyers could do stuff like that."

At the condo, a bodyguard protecting Pinnock was allegedly always present when Allums and Nobles and their son — Pinnock's grandson — visited. One day the family was hanging out at the condo, the couple said, when Nobles found what he believed to be a microphone plugged in behind the television. Nobles said he unplugged the device, which allegedly drew Harper to the condo, and the two had a showdown. Neither went into detail about what exactly was said — or shouted — but Nobles remarked that it got "really bad, to where it's like, this is real unprofessional."

Pinnock, meanwhile, had been "brainwashed," according to Allums. "At this point [Harper] had my mama all sucked into her lil' loop; 'Caree loves me. She's my friend.' I'm like, 'No, there's a difference between a friend and a lawyer. She's your lawyer.' But she had my mama thinking, Oh, I love you."

The family spokesperson role shifted from Allums to Pinnock's aunt, while Pinnock gave interviews to CBS News and the Associated Press with Harper by her side. Allums, who once locked arms with Harper in front of news cameras, was nowhere to be seen. By the end of September — less than three months after Pinnock's beating — a settlement was announced: Pinnock would be paid $1.5 million. Allums heard about it from someone who heard it on the news.

"We didn't get to look over anything," Allums said. "We didn't know anything." She and Nobles felt "totally pushed out," and they stayed that way for months.

Harper maintains that Pinnock was her client and that her loyalty was with her client — "not with my client's daughter, not with my client's son-in-law," she said. "If my name is under this plaintiff, my loyalty is right fucking there. There's no doubt."

But by Harper’s own account, Pinnock was also more than a plaintiff to her, she said. Pinnock was "like a relative."

The lawyer and client would play badminton on the beach together, Harper said. "She loves tennis and she loves to swim. … A lot of her relatives didn't really want to take time with her, and we'd hang out, and she had some of my staff helping her get back into society. She didn't know how to use a cell phone. A lot of modern technologies went by the wayside when she was in another place."

In January 2015, Harper filmed a clip of Pinnock getting ready to drive a car for the first time in a decade. In the clip, Pinnock is beaming, laughing, a Coach-embossed wallet in her hand, buckling her seatbelt behind the steering wheel of a Mercedes Benz. (It's not clear who owned the Benz.)

"It got so weird," Nobles said. "And it was like there's nothing we can do. … We didn't know about anything until the lady went to jail."

On Feb. 17, 2015, federal Judge Otis D. Wright II held a telephone conference with Caree Harper, and Police Officer Daniel Andrew's attorney. Five months earlier, news outlets had reported Pinnock's settlement, yet the court case had not been formally dismissed. Judge Wright wanted to know why, and the reasons Harper presented to him were tangled up in the disbursement of Pinnock's funds to a special needs trust — a nontaxable trust fund for a disabled person — which required Harper to find and hire a specialized lawyer.

Harper told the judge that "until very recently I was paying all of her bills." Pinnock had been discharged from the hospital with "nothing and no money to get anything, not even a toothbrush," Harper said. Just that week, she planned to take Pinnock to a dentist appointment. Harper asked Judge Wright to maintain brief jurisdiction of the case, to handle any other outstanding financial issues. This alarmed the judge.

“I’m becoming somewhat concerned," Wright said, "the hiring of all these lawyers … is doing nothing except eroding this woman’s recovery.” He agreed to intervene with apparent skepticism. By the end of the phone call, Harper expressed regret over her request. "I almost feel like I’m being punished," she said.

Two weeks later, Harper was jailed on contempt of court charges. During the hearing preceding her detainment, Judge Wright questioned Harper over how she first met Pinnock. Harper said their first meeting happened in the county mental health institution, but that the circumstances were "something I don't discuss with a third party." He continued asking questions, and Harper continued evading them, claiming attorney-client privilege.

At the same hearing, the judge compelled Harper to turn over her contingency fee agreement (the retainer contract) and the settlement agreement. The latter revealed that of the $1.5 million Pinnock was awarded, just $875,000 went to Pinnock alone — via her special needs trust — while $625,000 was directed to both Harper's law office and Pinnock, jointly. To Judge Wright, this appeared to be Harper taking a 41.66% fee — a fee on the high end of average for these types of cases, but not unheard of. But he criticized that figure, citing the very swift settlement proceeds and very strong video evidence. “No depositions were taken, no discovery was performed, literally nothing was done," the judge said. "I dare call this work."

The hearing was tense from the beginning, scattered with sarcasm and insults, all preserved publicly in court transcripts. The judge accused Harper of being "cute" and "playing games." Harper accused him of cross-examining her.

At one point, he asked Harper if she ever retained someone to look after Pinnock's interests — "given the fact that your first encounter with her was at a mental hospital" — like a conservator, someone who, by California's legal definition, "[cares] for another adult … who cannot care for himself or herself or manage his or her own finances."

At first Harper responded that she didn't have the standing to institute a conservator for Pinnock, who has never had one — then began to claim attorney-client privilege. Wright pushed back, telling Harper, "It's really quite easy. Either you appointed someone, hired someone, consulted with someone who would look after her interest — OK? — who would review the retainer agreement, who would review the settlement agreement, to whom you could discuss the terms of the settlement, for example, to make sure that her interests were safeguarded. I'm asking whether or not that dawned on you to secure someone to do that?"

Harper then answered; in addition to being the person who drew up Pinnock's retainer and settlement agreements, she was also "her advocate," she said, who "looked after her best interest." She added that Pinnock's aunt — who hadn't seen Pinnock in more than a decade prior to the freeway beating — and Allums and Nobles were also "privy to the settlement agreement and the retainer agreement." Allums and Nobles have fiercely denied being included in any settlement conversations.

When Wright ordered her escorted to L.A.'s Metropolitan Detention Center shortly after, Harper exclaimed that she had chest pains and a torn rotator cuff. What's not in the court transcript is Harper's subsequent screaming, she said.

"They seized me violently. They pointed a Taser in my fucking face," Harper said. "[The judge] fucking stood, clapped, and fucking laughed when I was screaming in pain." (This allegation is also detailed a complaint Harper later filed against the judge — that document is sealed, but Harper published an apparent copy on her website.)

Harper wouldn't say much about her two-day detention, which she’s referred to on Twitter as a “political arrest.” "I mean, shit, I'm not going to go too in-depth with it,” she said. “What did you want to know? That I tried not to drink any water so I didn't have to pee while being videotaped the entire two days?" She called the experience "humiliating." She said she suffered an exasperation of a pre-existing injury because of how officers handled her.

The detention lasted two days. Back in court, Harper told the judge she didn't know their last meeting would be an interrogation, which provoked Wright again. "You’re playing games again?" he said. "I thought I made it clear, I’m not the guy."

Harper answered the judge's questions, with some protest. But she told Wright again that she didn't receive 42% of the settlement; the $625,000 he identified as hers, she explained, was in both Harper and Pinnock's name. Of that sum, she said, $25,000 in cash went to Pinnock. This would drop Harper's fee to $600,000, or 40%. The judge asked for proof of the transaction, which Harper later filed.

But Harper has still maintained that she didn't receive 40%. In August, she said that she had waived costs and expenses in the tens of thousands. A lawyer in another state with experience in police abuse cases — the kind that typically involve discovery and depositions — told BuzzFeed News that contingency fees in these cases are typically between 33% and 40%, but that costs and expenses — which aren’t factored into the aforementioned fee — can sometimes together account for up to 70% of the overall settlement. Since Harper said she waived costs and expenses, this could explain why she maintains she didn't net $600,000, even if she did technically receive $600,000. But Harper declined to discuss any of this further.

"I would think it's improper to ask you how much money you make, and I shouldn't have to," Harper said, sounding both incensed and rehearsed, as lawyers often do. "It's not that I'm ashamed of it, because actually it should be raised, to be honest with you. It's not a personal injury case. ... This is not a fucking hit-and-run. It's not a car accident."

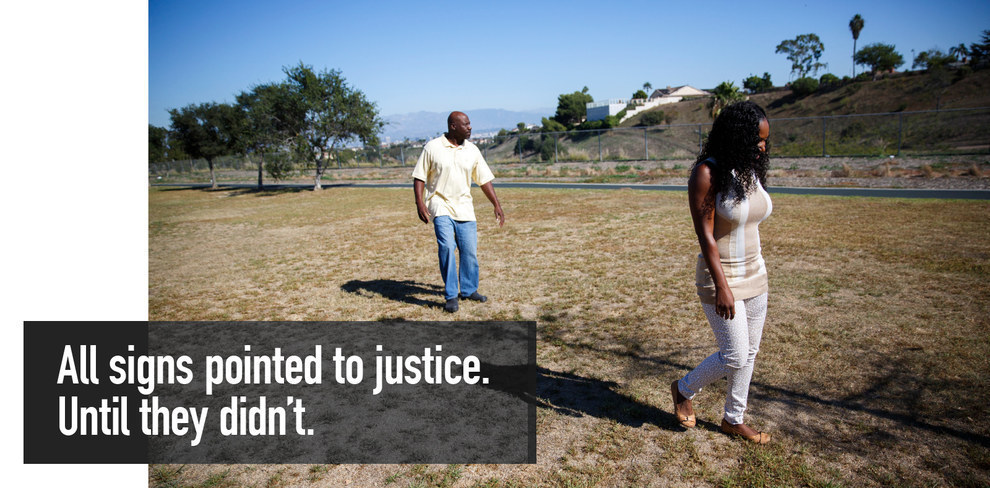

Maisha Allums and Robert Nobles both work for the school district in Torrance, south of Los Angeles. Nobles coaches football, basketball, and track, and Allums works for campus security. They were driving home from work when the news of Harper's arrest reached them. They couldn't wait; they pulled to the side of the highway, Nobles said, and found the judge's office phone number. They spoke to Judge Wright for an hour, still sitting in the car, going over what had happened in court. The judge asked them to appear at the next hearing.

And so Allums and Nobles told their story — albeit a more condensed version — in court on March 17. Harper wasn't there; she had sent two lawyers from celebrity law firm Geragos & Geragos in her place. The judge summarized events, saying that he was "terribly concerned that [Pinnock] probably did not understand the contracts that Ms. Harper was sticking in front of her and asking her to sign.”

But also in court was a group of people gathered to support Harper, including Pinnock's aunt, Brenda Hall-Woods, who told the judge that Harper was "a fair, honest person, as far as I’m concerned. … She got Marlene out, she put Marlene up."

Wright went through it all again, saying "no work was done" and calling Harper’s fee "unconscionable": "No one was looking after Ms. Pinnock's interests. Ms. Pinnock, in my opinion, has been exploited, and Ms. Harper doesn't want to answer my questions.”

"My interest is fairness," the judge continued, "I am not going to have this woman, mentally ill, when everybody knows she's mentally ill, being preyed upon, being used and stolen from."

One of Harper's supporters urged Wright to look at the bigger picture, saying, "This is going on every day throughout the United States. And we have someone now that is defending us, and you're stuck on money. And if you silence Ms. Harper, who else do we have to speak up for the people? You want her to stop—”

The judge interrupted. “Exploiting," he said. "I want her to stop exploiting."

“You're making an example of Ms. Harper because of the financial situation,” another supporter said.

"Yes," the judge replied. Yet at the end of the hearing, Wright resolved the matter, apparently satisfied by Harper's attorneys providing documentation of Pinnock's special needs trust. The judge declined to speak to BuzzFeed News for this story.

The next month, when Harper gave her first post-detainment interview to L.A.'s CBS affiliate, Hall-Woods (Pinnock's aunt) and Pinnock herself also went on camera.

Hall-Woods — who said she hadn't seen Pinnock in 13 years before the freeway beating — slammed Allums and Nobles for being "all about the dollar bill" and blamed them for Pinnock being on the streets in the first place, claiming they "put her out." She emphasized Pinnock was "a little nervous off her medication," but that "she is by no means mentally incompetent of handling her life. … She’s fine. There’s no problem there."

She also praised Harper, explaining the attorney is "her niece now. I call her my niece."

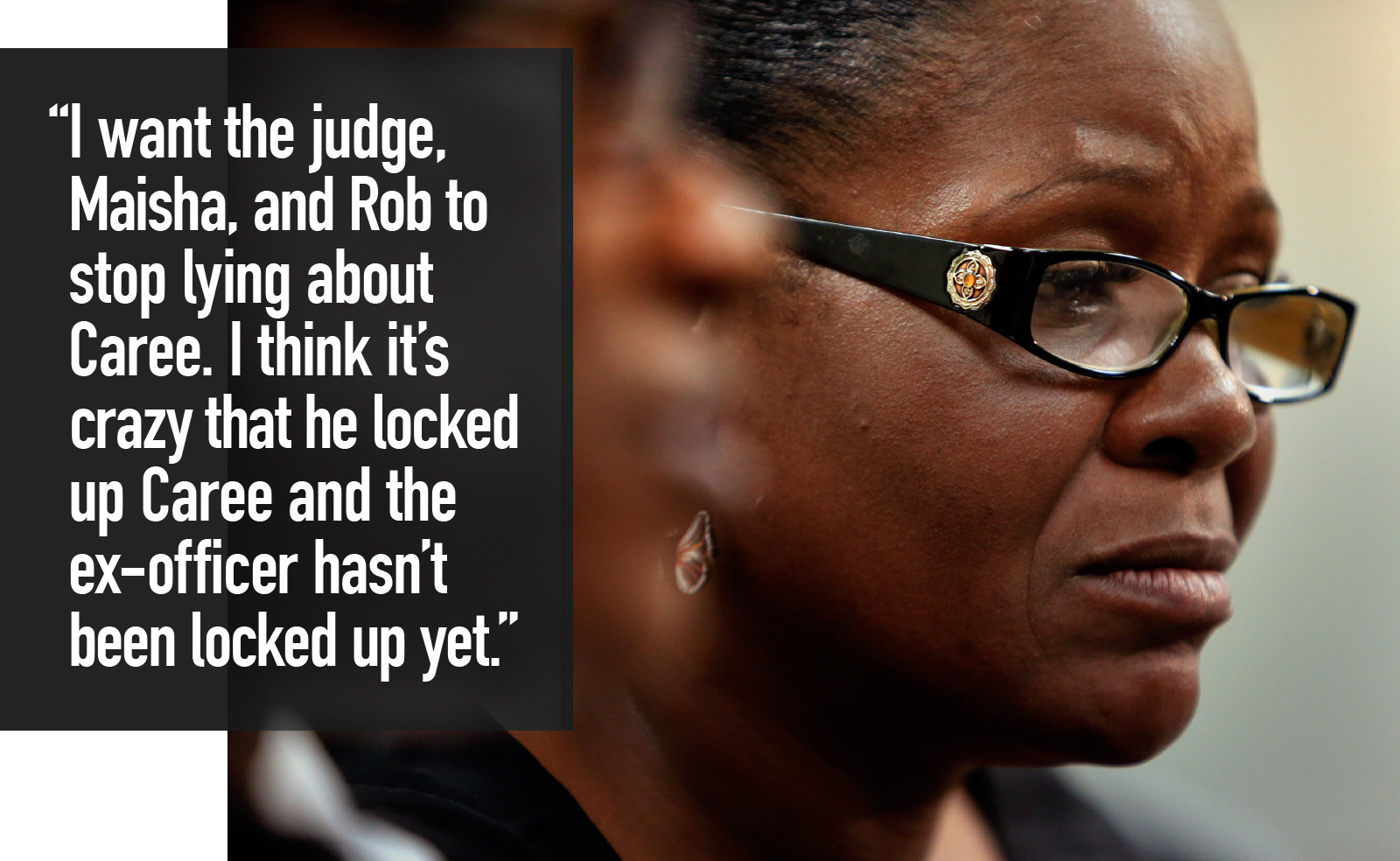

Publicly, Pinnock too has shown only appreciation and support for Harper. In her interview, she wore a black skirt, a yellow printed top, and glasses, her hair long and wavy, and spoke carefully, reading from two pieces of paper in front of her.

"First, I'm happy, and I'm happy with the work that my attorney did and still does for me. I do not want the judge, my daughter, or her husband making decisions I can make on my own. I want the judge, Maisha, and Rob [Allums and Nobles] to stop lying about Caree. I think it's crazy that he locked up Caree and the ex-officer hasn't been locked up yet.

"Just because I'm on medication does not mean I don't know what's going on around me and what's going on with my finances. Once again, I'm happy."

Online, there are several complaints against Harper on a variety of consumer complaint websites — popular places for airing grievances about lawyers. Most are about her upfront fees. One complaint became the subject of a defamation lawsuit Harper brought against a disgruntled ex-client in 2010, who wrote on RipoffReport.com that Harper had robbed her. Harper won the suit.

Harper has filed other complaints on her own behalf, including against her former employer, the Fairfield Police Department. (That case was brought in 2005 and settled.) In her often-heated hour-long interview with me, Harper made only brief reference to being a police officer, claiming she won "a life-saving medal for jumping in a canal when I had a fear of water and saving somebody's life — a white man's life."

But Harper's past is something she has in common with Judge Wright (whom she likes to call “Judge Wrong”). He spent 11 years as a deputy sheriff with Los Angeles County. Wright, who was nominated for his position by President George W. Bush in 2007, has also made headlines, for better and worse.

In 2013, Wright accused a "porno-trolling collective" of lawyers of "moral turpitude" in a "scathing decision" riddled with Star Trek references. Wright is also known for his 2014 ruling against the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives over its fake stings. Two years before that ruling, Wright made the Wall Street Journal after he and his wife filed for bankruptcy, "a rare thing for a federal judge." There are plenty of online complaints about Wright, too, on The Robing Room, a sort of Yelp for reviewing judges. Commenters call him "incompetent, arrogant, and rude" or "rude, arrogant, temperamental" or "stupid, incompetent, AND rude."

After her arrest, Harper filed a complaint against Wright with the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. In the complaint, she called Wright "sadistic," saying he held a "trial by ambush" in his courtroom, leading a "slanderous attack" on Harper and not providing her due process before her detainment.

But the complaint also accused Allums and Nobles of misrepresenting Pinnock's mental health in court — Allums believes her mother suffers from schizophrenic symptoms when she's off her bipolar medication and drinking, though Pinnock has not been officially diagnosed with schizophrenia. Harper also says Pinnock's daughter wanted "to control her mother's money."

"Before Ms. Pinnock was released from the hospital in July, 2014, Ms. Allums and Mr. Nobles were house-shopping and inquired about how much of Ms. Pinnock’s anticipated money they would receive," Harper wrote. (Allums and Nobles said they never received money from Pinnock's settlement, nor were they concerned with getting any. They denied going house shopping.)

Harper has otherwise remained silent on Allums and Nobles, telling me in August only that they "maybe can use some prayers." As for Judge Wright, Harper has continued to be publicly critical. Last month, Harper tweeted that Wright's "unconstitutional jailing of lawyer in #CHPbeating caused breakdown of #MarlenePinnock's support group. Now what?"

In the days after Pinnock's beating, Allums and Nobles spoke with Harper about how big Pinnock's case could become, they said. They saw an opportunity to amplify Pinnock's story and help black people — particularly those living with mental illness — brutalized by the police. By the time Pinnock's settlement was reached, Black Lives Matter demonstrations had erupted not only in Ferguson, Missouri, but all over the country.

"We had that talk like, 'This could make or break your career, dude, so I hope you're ready to really put the boots on and be a bulldog for this case,'" Nobles said.

But after the first massive wave of attention to Pinnock's beating, only local media really stuck with the story. Few rallies or protests were held for Pinnock. And Allums and Nobles blame Harper for that.

"It was swept under the rug," Nobles said. "I can't believe it. I still cannot believe it."

Harper gave dozens of interviews — local and national — as Pinnock's lawyer and spokesperson. But her relationship with the media became hostile. Today she says she's "really fucking sick of the LA Times," referring to one reporter there as a "little fucked-up dweeb." She tells me that if I use the word "exploit" in this story, I'm attacking her. She hints at litigation for the Los Angeles Times or anyone who uses "the e-word" out of context.

But Harper doesn’t readily accept Allums and Nobles' blame for the dwindled interest in Pinnock’s case. "I think that people kind of want to put their head under the covers and say, 'I just want this stuff to stop,'" she said. "You come to a point, any human would come to a point, where it's sensory overload."

Harper likes to point out that the L.A. Times wrote three stories this spring about her and none about Daniel Andrew, the man who pummeled Pinnock. She's right; in the year the district attorney spent investigating Andrew, no stories were written about the officer or the case, outside Harper's detainment. Even in this story, the one you're reading now, Andrew and the DA are minor characters.

With the DA's announcement that Daniel Andrew "acted within the law," the former officer's freedom opened up an old wound for Allums and Nobles.

"All you have to do is watch the tape," Allums said. "I don't understand how that was protecting my mom." Even so, she said, the sting of Harper's alleged mistreatment has felt almost equally strong for them.

"Everybody's so focused on the police officer, and what he did was wrong," Allums said in court in March, "but what Caree Harper did to my mom was also wrong, too — what she did to me. She manipulated me. She isolated me from my mom. I mean, my mom [and I] had a close relationship. ... Yes, she would run off and do stuff, and I couldn't control her. And I told Caree Harper all this. She took advantage of everything that I told her and didn't do nothing that she promised me."

"We're not rich," Nobles said in August, pointing to various corners of their modest apartment. "We work real, real hard but you see where we live. So to take advantage of a family unit like that is criminal."

In a statement to BuzzFeed News on Friday, Harper said that she is "very proud of the services and support my office has provided and CONTINUES to provide for Ms. Marlene Pinnock" — that she has "a long, proud history of community service and pro bono work." She said that she hopes this story focuses on the need for special prosecutors and the DA's failure to charge Andrew, rather than "the sideshows." And she said that one could question my motivation for reporting this story, given the "inappropriate, condescending, invasive" questions I asked her regarding Allums and Nobles' allegations.

On Sept. 11, Allums was driving home from her son's football practice, merging onto Interstate 10 via the La Brea ramp, when something caught her eye on the side of the highway. She glanced over, she said, and saw her mother sitting on the ground, handcuffed. Allums made her way to the next exit and circled back to La Brea. But back on the ramp, Pinnock had already been taken away, Allums said.

Police put Pinnock on a 72-hour mental evaluation hold — which Allums learned later that night, after calling a few local stations. But Allums wasn’t told where Pinnock was being held, she said. She could find that out only if her mother decided to call her. Pinnock didn't call.

After the 72-hour hold, Allums said she drove by the spots she knew Pinnock often stayed, but she couldn't find her. "I don't know if she changed her location because she knows I'm looking for her," she said. Allums hoped her mother would stop by her apartment to take a shower or a nap — as she does sporadically — but she didn't. When she gets "really really sick," Allums said, Pinnock stays away.

On Oct. 6, just before 2:30 a.m., Pinnock was detained again for wandering the freeway. This 5150 hold, unlike September's, caught the eye of reporters, putting Pinnock back in the news for the first time since Caree Harper and Judge Wright's spring clash. Allums said she didn't find out about the arrest until the L.A. Times contacted her for comment. Nearly two weeks went by before Allums spoke to her mother or her mother's doctor, she said.

Pinnock's hospitalization continued. At first she didn't "really say too much," Allums said. "She feels everyone is crazy except her. She thinks if she wants to be on the freeway than she should be able to be on the freeway."

Allums hadn't heard a word from Caree Harper for months, until Nov. 18, when Pinnock had a hearing at Los Angeles's Mental Health Courthouse to determine her medical future. Prior to the hearing, Pinnock's doctors recommended to Allums that Pinnock continue receiving treatment for another six to nine months. Allums agreed. "If she doesn't get help," she said, "I feel like she's gonna end up dead or hurt or get someone else dead or hurt, and then it's a whole 'nother ball game, because then it's jail time."

The plan was for Allums and the doctors to present their recommendation to the court — and Allums to finally become Pinnock's conservator. But right before the hearing, Pinnock announced she was "gonna do something different," Allums said. Waiting at the courthouse were Caree Harper and Pinnock's aunt.

Mental health hearings are confidential, but Allums said that Harper argued before the judge that Allums wants to lock Pinnock up and gain access to her money — that Pinnock had been stable for nine months prior to the latest freeway incident. Harper wore a boot on her foot, telling the judge she'd just had surgery and asking for an extension before any ruling, Allums said. According to an L.A. activist's blog post citing information from Harper, the extension request was made so that Pinnock could "hire her own lawyers and doctors to assist in fighting her daughter and son-in-law."

There were other hearings — again, confidential — regarding Pinnock's future on Dec. 2 and Dec. 10, but Allums was unable to attend both. She's still waiting to hear from her mother's trust fund representatives and doctors about what happens next. As of Friday, Dec. 13, Allums said, Pinnock remained in a county facility. And Allums said she's reached the point of exhaustion.

"Sometimes it feels like I'm the only one trying to help her," she said. "It doesn't seem like it's paying off."

Nine months ago, Judge Wright asked Caree Harper if Pinnock should have a public guardian established for her. At the time, Harper objected to weighing in. "She’s currently living on her own. She’s acquired a California driver’s license. She’s driving on her own, and she’s medicated,” the lawyer said. “How can I say that a 52-year-old should have a public guardian? I’m not in a position to say that.”

It's unclear how Pinnock went from living on her own and driving and medicated in the spring to transient and unmedicated in the summer to arrested and hospitalized in the fall. This summer, Harper told me that Pinnock had a home "ready, willing, and able to accommodate her, if she chose to be there."

"She has this condo of her very own," Allums explained. "She still goes back to the freeway. I cannot make her stay nowhere. Anyone who's dealt with mental illness before knows: You can't make them do anything."

Allums and Nobles also said Pinnock has had a bedroom in their apartment "open for 15 years," if she wants it. But for about that same length of time — 15 years — they have felt powerless to help Pinnock or get help for themselves. They said they’ve tried calling the county's Psychiatric Emergency Team (PET) during Pinnock's occasional drop-bys, but Pinnock always leaves before the team arrives. When Pinnock is detained, they struggle to get information from the city or county, but also from Pinnock herself. And in their minds, this wasn’t supposed to be happening anymore. Though they’ve long struggled with Pinnock's illness, each of these recent struggles reminds them of the hope they felt when Caree Harper came with her offer to help.

“She should never practice law again and never manipulate another black family," Nobles said, back in August.

This summer, Allums and Nobles filed a complaint against Harper with the California State Bar, they said. They were told their complaint — which they declined to provide to BuzzFeed News — was being investigated.

The state bar wouldn't confirm whether an investigation is underway. Harper, who has no disciplinary action on her record, maintains she has "no open investigations for anything." This summer, though, she did mention a "witch hunt" that was limiting her ability to help Pinnock.

"Sometimes I see things that could be made better," she said. "And of course I want to make things better, but you know really especially with the witch hunt on me, there's certain limitations that I have."

"But I don't want [Pinnock's] story to be that of a story that's not of success," Harper continued. "Because for the last year she's been a great path — for a year — which is a year longer than any other time in the last 10 years. … She's very smart. Sometimes even smart people detach from things sometimes."

Harper has gone on to represent other clients, including Clinton Alford, a 22-year-old black man who was beaten by a Los Angeles Police Department officer while detained last October. But today, Harper still has a prominent section on her website devoted to the Pinnock case — which drives Allums crazy, she said.

"On her website at first, all you saw was Marlene Pinnock, Marlene Pinnock, Marlene Pinnock," Allums said. "She's the one that ended up getting helped. My mom didn't get helped; I didn't get helped. You know, our family didn't get helped."

"And on this day, our mom... " Nobles said.

"Is back to square one," Allums finished.

"Back to square one."