On March 4, about 500 women in downtown Los Angeles experienced time travel. These women, mostly youngish and progressive-leaning, wide-eyed and well-dressed, entered a bright, lofty industrial building just before 9 a.m. They took a freight elevator, illuminated by pink neon lights, up to the fourth floor. And for the next 12 hours, give or take, they returned to the state their lives were in before Donald Trump became a serious candidate for president.

Remember those days? Before the country heard a presidential candidate say "grab 'em by the pussy"? Before November 9 became a day of mourning for most of Hillary Clinton's 65.8 million voters? Before scores of women, on the day after Trump's inauguration, became the leaders of the #resistance with a worldwide march, shaking the women's movement from its decades-long slumber?

Because by President Obama's second term, there simply wasn't a women's movement, at least in the raucous political sense. Feminist activists were still out there — fighting for reproductive rights and against sexual violence, joining Black Lives Matter — but the movement that attracted the most attention was the up-the-corporate-ladder kind. Empowerment was catchier than equality. Powerful women in business became the faces of modern (white) feminism, even if they expressed little interest in feminism itself.

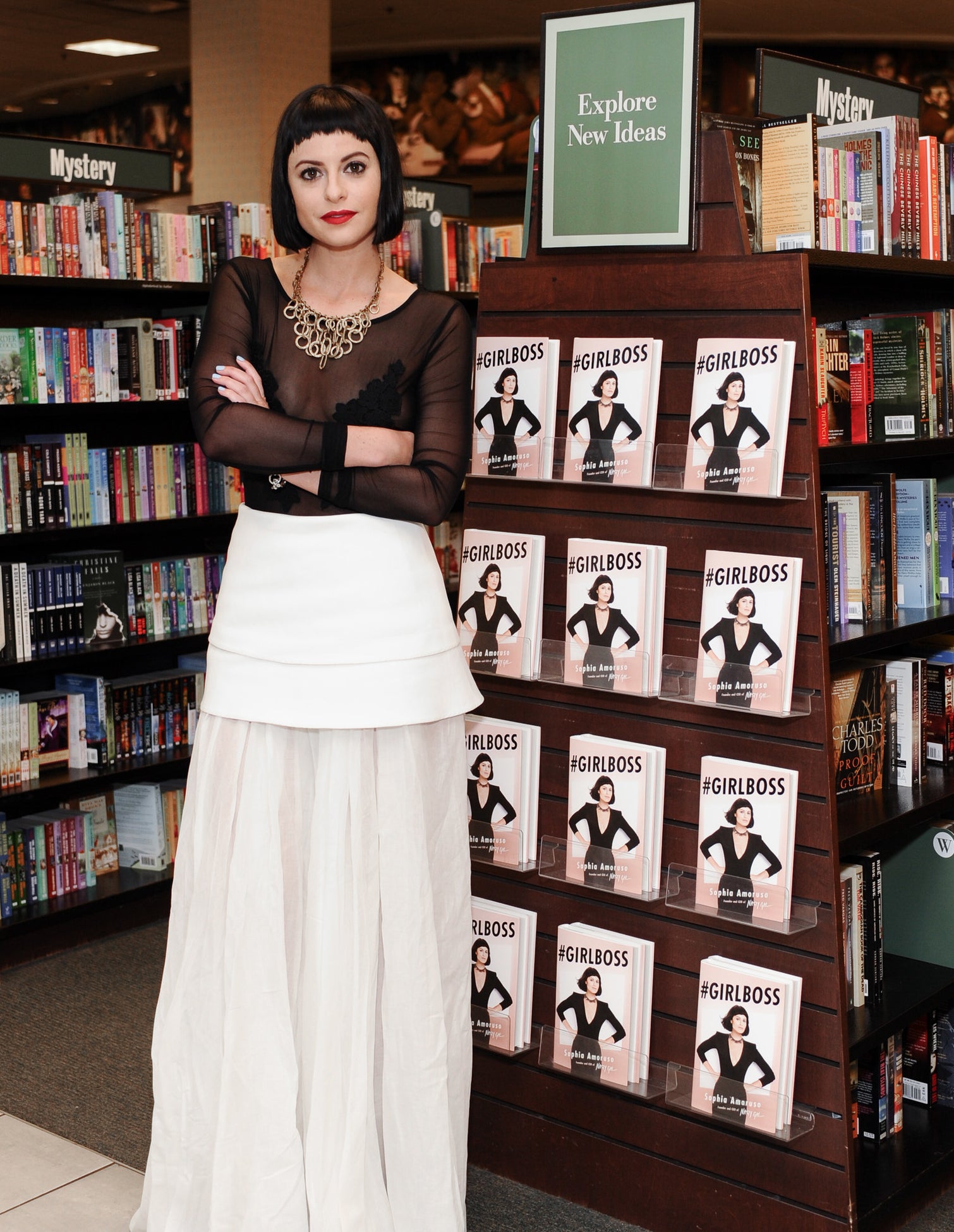

Enter Sophia Amoruso, entrepreneur and proprietor of Girlboss, a term she introduced in 2014 with her best-selling book #Girlboss and doubled down on in 2017 with the inaugural Girlboss Rally — the event that brought these 500 women to downtown LA on a Saturday in March.

When it was announced in December, the one-day conference seemed almost like Amoruso's answer to post-election anxiety. "When I wrote #Girlboss nearly three years ago, I had no idea how necessary it would be," Amoruso said in her Instagram announcement. "The world has moved backward in 2016, putting even more pressure on us to collaborate, co-conspire, and create a vision of the future together."

The rally was also the first production of Amoruso's new women's digital media company, Girlboss Media. The goal of the company, Amoruso later told me, is "to inspire and inform and educate and entertain girls, women, to be their best selves and to define success for themselves."

Can Girlboss Media succeed without reflecting the tectonic shift the election wrought for its audience?

Girlboss Media's online content and IRL events (like the rally) will focus on work, personal finance, wellness, travel, and possibly fashion, Amoruso said — an extension of the topics she wrote about in #Girlboss. But there's something missing from that list. This is 2017, not 2014, and in those three years, the world as Amoruso's audience knows it has changed. Young women have descended their corporate ladders to join the marches. Mainstream feminism has gone political again, and women's media has largely followed suit.

Girlboss, though, has no plans to embrace politics in a significant way, Amoruso said. The company already has name recognition and Amoruso's loyal follower base (450,000 followers on Instagram alone) to get it going. But can it succeed without reflecting the tectonic shift the election wrought for its audience?

That depends on what happens to mainstream feminism next: whether it slides back into careerism, the place #Girlboss flourished, or whether it maintains the political urgency brought on by President Trump. And that means, once again, Amoruso has found herself at the center of feminism's evergreen identity crisis, a murky, tangled, infinite jungle she never intended to enter.

In the years before the election, the media was fixated on young women's personal and professional advancement, obsessed with narratives of empowerment. Mainstream feminism was a worn copy of Lean In, a Dove soap commercial, a viral video about catcalling, a celebrity standing up to her haters. There were many firsts: A woman won the Nobel Prize in Economics, a girl pitched a winning game in the Little League World Series, and the first female nominee of a major political party ran for president. What more could the modern feminist want?

So she turned her attention to her career, to bridging the gender gaps she saw in her daily life. The Lean In feminist networked, climbed, and got paid. She was young, social, and probably white (but woke, she'd remind you). And there's a good chance she’d read #Girlboss, the part-memoir-part-business-advice book published by Amoruso, then the 30-year-old CEO of fashion e-commerce company Nasty Gal.

#Girlboss spent 18 weeks on the best-seller list, received by critics as Lean In for millennials. But the book found its following because it wasn't anything like Lean In. Amoruso was a cutting, cunning community-college dropout, far more relatable to most young women than Sheryl Sandberg with her two Harvard degrees and two kids.

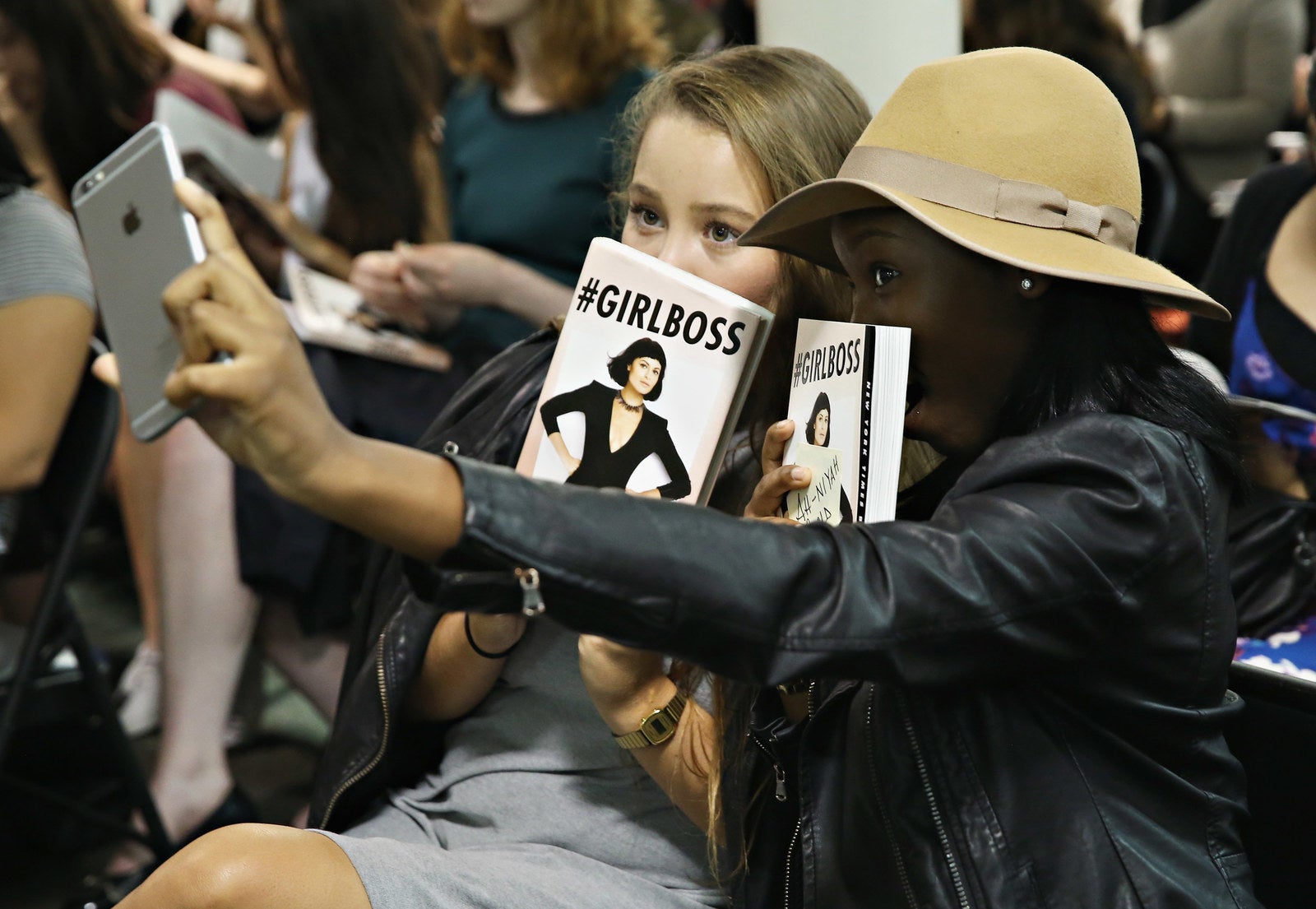

Amoruso's rags-to-riches story meant something to these young women, who turned #Girlboss into a kind of status symbol. She read the book, and then she posted an Instagram of her copy, carefully askew beside her mid-morning matcha latte, and then her friends bought the book (and a matcha latte). In 2015, #Girlboss became Girlboss Radio, a popular podcast, but by then it barely mattered what form of media Amoruso chose. Girlboss was not a book but "a movement," as Lena Dunham opined.

Girlboss, like much of popular feminism in 2014, had never really been about political action. But the election, Clinton's loss, and the women-led protests against President Trump massively shifted the focus of mainstream feminism. Millions of women expressed outrage they hadn't before at politicians and the misogyny they believed propelled Trump to victory. They marched on DC, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, in the island town of Adak, Alaska, and in the border town of Ajo, Arizona. The personal and professional advancement that felt so urgent in the Obama years suddenly didn't matter — not compared with the millions of Americans who now feared being targeted by the Trump administration based on their gender, race, sexual orientation, and religion.

As progressive women imagined a world stripped of fundamental rights, there was little talk of having it all, or leaning in, or being bossy, or banning bossy. More women showed interest in running for office. More donations poured into Planned Parenthood, including $1 million from Sandberg, Lean In's author and patron aunt of Obama-era feminism, who until then had kept her donations to the organization quiet. Issues that feminists may have once allowed to occupy a gray space were now forced into black or white. Ivanka Trump was either with women or against women; all Trump voters were misogynists, period. When the Women's March was called out for partnering with women-led anti-abortion groups, the organizers had to choose a side. (They chose their powerful supporters like Planned Parenthood.)

Amoruso, who attended the Women's March in LA, sensed this reorientation of popular feminism. Accompanying her announcement of the Girlboss Rally was a black and white photo from a 1970 women's liberation protest in Toronto, which became one of the Girlboss Rally's main promotional images. The event sold out five weeks later — on the day before Trump's inauguration.

But the appeal of the rally wasn't just the "actionable takeaways" for the "next generation of curious creatives" that Amoruso promised. It was also about hearing from Amoruso herself. The year after #Girlboss's publication, Amoruso's meteoric success began falling apart. She stepped down as CEO of Nasty Gal. There were layoffs and rumors of financial peril, and reports (she denied) of Nasty Gal firing pregnant employees. The day after the 2016 election, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It was a delicious parallel for critics of both Amoruso the Nasty Gal and Clinton the Nasty Woman. Amoruso's big brand of career-focused feminism couldn't save her career — Clinton's couldn't save hers either.

Still, Amoruso's followers didn't turn on her; they knew setbacks had always been part of the #Girlboss story. And so they turned out en masse to support her big comeback: the Girlboss Rally.

Just after 9 a.m. on March 4, Amoruso gave the longest speech she's ever given, at six and a half minutes. Her public appearances are typically formatted as Q&As, she explained. This — her opening remarks at the Girlboss Rally — was different. She was speaking directly to her audience, for perhaps the first time since her book tours for #Girlboss.

She stood onstage, note cards in hand, a slightly nervous figure against a playful ’80s-futuristic pink, red, and purple backdrop. Nearly every phone camera in the room was trained on her.

"There was a time when I was the archetype of success," she told the crowd of 500, referencing her tumble from "40 under 40 and 30 under 30" to bankruptcy. "I don't have it figured out, and I hope I never do, and I hope you never do. And that's why we all get to keep learning. And that's what we're all here today to do."

Amoruso wore a black jumpsuit, long-sleeved and slim-fitting, cut with a deep V-neck and framed by sharp shoulder pads, reminiscent of the black dress she wore on the #Girlboss book cover. The parallel felt intentional; this is still the Girlboss you know and love, even if some things have changed.

"So what's Girlboss?" Amoruso continued. "I'm going to start by telling you what it's not. It's not a book. But I did write a book called #Girlboss. It's not a new Netflix series. Although there's a really funny show coming to Netflix in April called Girlboss. Girlboss is a feeling; it's a philosophy. It's a way for women to reframe success for ourselves on our own terms for the first time in history."

The short version of Amoruso's success story goes like this: After a few years of on-and-off employment — supplemented by shoplifting and dumpster-diving — and flirtations with postsecondary education, Amoruso started an eBay store for vintage clothing in 2006. She called it Nasty Gal. By 2014, that eBay shop had blossomed into a multimillion-dollar e-commerce website, collecting 350 employees along the way. The Nasty Gal wardrobe was aggressively trendy, sometimes edgy, and often affordable. Malia Obama once made headlines for stepping off Air Force Two in a $78 dress sold by the brand.

As an entrepreneur, Amoruso was already a character — with her Black Sabbath T-shirts and distaste for industry traditions like Fashion Week — but #Girlboss made Amoruso an icon among her audience: women under 30. Her book, she said, was "neither a feminist manifesto nor a memoir." She defined a #Girlboss as "someone who's in charge of her own life," a hardworking, responsibility-accepting but occasionally rule-breaking go-getter who was simultaneously — perhaps impossibly — super chill.

"You know where you're going, but can't do it without having some fun along the way," she wrote. "You take your life seriously, but you don't take yourself too seriously. You're going to take over the world, and change it in the process. You're a badass."

Despite the nearly three years between them, the Girlboss Rally's programming was remarkably consistent with #Girlboss. In the book, Amoruso implored readers to have professional LinkedIn photos (no sunglasses); the rally offered free professional headshots, preceded by free makeovers from a curling iron–armed glamsquad. (The wait for these headshots was, at times, at least an hour.) Also in the book, Amoruso explained that she believed in "chaos magic," "the idea that a particular set of beliefs serves as an active force in the world," often practiced through "sigils, which are abstract words or symbols you create and embed with your wishes." The Girlboss Rally’s first presenter following Amoruso's remarks, Gabby Bernstein, was a motivational speaker who encouraged similar spiritual practices: setting intentions, visualizing goals, communicating your dreams into the universe.

#Girlboss is also essentially a text of self-promotion, not just for Amoruso but for her company; the book's final moment dwells on Amoruso walking into the Nasty Gal offices and realizing "we've arrived, and we're killing it." Since Amoruso’s Nasty Gal doesn't exist anymore, she used the final moment of the Girlboss Rally to advertise the upcoming Netflix show Girlboss, appearing onstage alongside the showrunner, star, executive producer, and costume designer. (Amoruso is also an executive producer.)

There was one big difference between the book and the rally, though: The latter featured many, many women.

More than three-quarters of the business and cultural figures quoted throughout #Girlboss are men — including Donald Trump, whom Amoruso quotes at the start of a section on how to fire people: "Generally I like other people to fire, because it's always a lousy task." In the book, men often play more dynamic roles in Amoruso's life: trusted investor, mentor (in business and in shoplifting), inspiring high school teacher, boyfriend, photographer. The women are more often employees, customers, models, competitors, or idiot travel companions. The book makes no plea to lift up other women, or to lean on other women for mentorship. A #Girlboss is on her own.

Amoruso today is more devoted to sharing her platform with women. Her rally had just two male panelists compared with 40 female speakers. On her podcast, she interviews prominent women each and every episode. Her Girlboss Foundation has contributed more than $120,000 to fund small women-owned creative businesses.

But it's still unclear if Amoruso has any interest in deeply exploring the "girl" part of Girlboss. Gender has never been something Amoruso "had to overcome," she wrote in her book.

"Is 2014 a new era of feminism where we don't have to talk about it? I don't know, but I want to pretend that it is," she wrote. "If this is a man's world, who cares? I'm still really glad to be a girl in it."

When I mentioned that line to her, nearly four years after she wrote it, Amoruso laughed. “It was such a different time! It's almost like an irresponsible thing to say," she said. "But who knew?”

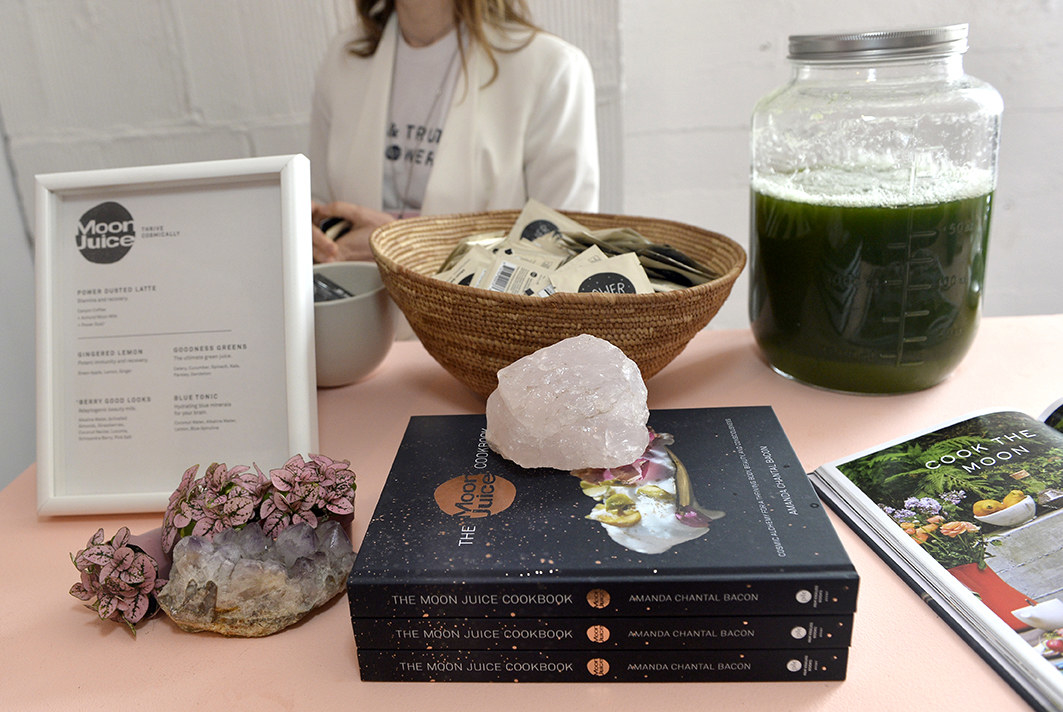

The morning of the Girlboss Rally continued with panels from a cancer survivor turned model, a millennial marketing researcher, investors, a YouTube star, and a new-age wellness guru — that's Amanda Chantal Bacon, whose A-list–approved Los Angeles company Moon Juice also offered free lattes to attendees. The lattes were spiked with "Power Dust," an herbal supplement blend to boost "peak performance, stamina, and longevity," and there was always a line for the drinks, until Moon Juice ran out of ingredients sometime around 4 p.m.

In the brief rests between panels, and during two separate lunch breaks, the rally-going women convened in a stylish lounge space, resting their free Sweetgreen salads on their laps, comparing notes and often outfits. There were no blinding-hot pink "pussyhats" here — rather the numb, pale “millennial pink” was everywhere: on their dresses and blazers and bags and the badges around their necks, on the walls around them, and painted on once naturally green houseplants in every corner. At one point I looked down at my pink shoes and wondered if they were even a choice.

The women were abundantly polite and cheerful, smiling at strangers, paying attention during panels, and bonding with one another in the cavernous hall of porta-potties downstairs. They were all roughly the same age, 20 to 30, and largely white, though not entirely. They had come from over 15 countries, Amoruso later said, including Brazil, the UK, France, South Africa, the Dominican Republic, Australia, and Canada. During breaks, their voices filled the lounge, creating one expanding mass of indistinguishable chatter that filled the space up to its high, whitewashed ceilings. Organizers encouraged anyone overwhelmed by the crowd to go to the rooftop "if you need a break" — the rally was, after all, created by a self-described introvert.

The event was meant to feel aspirational-within-reach. The Girlboss girl can afford her own $12 salads and $12 juices, though maybe not every day. Here she got them for free. The base ticket cost was $395 — a splurge, but not one as big as going to TEDWomen ($2,495) or Fortune's Most Powerful Women Summits ($10,000). Money was central to the Girlboss Rally, and nowhere more so than at Sallie Krawcheck's 4 p.m. career advice talk. Krawcheck didn't just get, in her words, "raw" about money. She talked briefly but bluntly about feminism today — one of the only panelists to do so.

Now the CEO and cofounder of Ellevest, an online investment platform for women, Krawcheck formerly ran wealth management at Citigroup and Bank of America before getting fired from both C-suite jobs — career setbacks she discussed at length before giving advice based on her professional roller coaster: Work hard, ask for feedback, get a sponsor, help other women, etc. But then, toward the end of her 54 minutes, she used the f-word.

"How does feminism need to change in a post-Trump world?" she asked. This was a jolt — the first time in seven hours someone had used anything resembling that phrase. “Post-Trump world.” A glitch in the time machine.

Krawcheck argued that women have been waiting "to be given power" from men when they should be working together to seize it for themselves. "We as women will not be equal with men until we are financially equal with men,” she said. “Money is power, and we saw what can happen in the last year when our power is taken away."

But when it came down to it, the Girlboss Rally, which brought together one of the most concentrated gatherings of young women since the Women's March, had just one hour-long panel devoted to current events. The early-evening panel, "The World's Gone Mad," featured Jessica Bennett, a journalist and contributing editor for Sandberg's Lean In Foundation; Alyssa Mastromonaco, an ex–Obama White House staffer turned television executive; and Moj Mahdara, chief executive of Beautycon Media.

Maybe it should have been a downer of a panel, but the three women pushed funny and engaging and mostly optimistic points of view, bonding with the audience over their post-election grieving stories. Mastromonaco said the election "made me rethink partisanship because I would give anything for Jeb Bush to be president." Mahdara said that, after the grieving period, she realized this was an "amazing cultural moment" in which "loving your country is exciting right now.”

"The days of people saying ‘I’m not really into politics,’ or ‘That’s not something I really talk about,' has sort of come to an end," she said. "I can't recall ever caring who was gonna be the head of the FDA until now."

But it was roughly 38 minutes into the politics panel before the three women offered advice on political action, and only after a college student raised her hand to ask what she could do. "While this is a day about empowerment, there's some really bad shit going on," the girl said. "It feels like the millennials' job to fix what's been going on."

The panel’s suggestions included voting, volunteering on campaigns, running for local office, and generally "getting involved."

"Also, I didn't know that it was actually effective to call your congressperson," Bennett said. "You have to get over your fear and call."

It was hardly a call to arms, but the conversation was at least solidly rooted in politics and current events and feminism amid the vision-board bent of other panels: "pursuing your dreams fearlessly," building confidence, preserving creativity, and "sex, health, and consciousness" — in which a panelist demonstrated a technique for self-stimulated orgasm through breathing.

As night fell in LA, neon lights that had been on throughout the day became more pronounced in the dark, dizzying and dreamlike, casting everyone's skin in a warm, feature-erasing pink. The washed-out faces listened to Amoruso interview Instagram co-founder and token man Kevin Systrom, and then, finally, the panel on the Netflix show. The series, debuting April 21, was created by Kay Cannon, who wrote the Pitch Perfect films and worked on New Girl and 30 Rock.

Girlboss will not adhere closely to Amoruso's life. But it will be a "success story, a failure story, a can't-take-a-good-girl-down story," Cannon said at the rally. That kind of story, she argued, is important in today's "very specific political arena," where "as women, it feels we're all collectively taking a couple steps back," Cannon said.

"In this political climate, it's so great to see a woman learn her power," added costume designer Audrey Fisher.

But it's exactly this kind of success-story-as-manifesto that inflames critics of career-focused feminism. In her 2017 manifesto, Why I Am Not a Feminist, the radical writer Jessa Crispin scorched Amoruso and Sandberg without even naming them: "If feminism is nothing more than personal gain disguised as political progress, then it is not for me," she wrote.

After the panel, as a group of women boarded the freight elevator, a dirty-blonde mutt wearing a millennial pink bandana snuck into the car with them, its owner nowhere in sight. The women stared at one another, wondering what to do about the dog. It had been a day. The time travel had been exhausting. "Am I hallucinating that dog?" one woman in pink said to her other friend in pink. While someone shooed the dog off the freight, another woman held her gift bag up to her face, peering through the plastic shell. The official Girlboss Rally swag was packaged in the same clear backpack that was omnipresent at the Women's March on Washington.

Among the treasure inside were two mascaras, a litany of coupons, skin care and shaving products, deodorant, two candles, an enamel pin reading "Babe With the Power," a tampon alternative, a pair of lace underwear, and a gift card from the company that makes the lace underwear declaring "The Future Is Female."

"Honestly this is worth the price of the ticket," the woman said.

There's an argument to be made that the Girlboss Rally's general omission of politics was deliberate — that Amoruso wanted to create a fantastic alternate reality where young women could catch a break from crushing reality, where they could momentarily stop worrying about geopolitical strife and take care of themselves, where they could return to the world they lived in before they watched the only woman to ever have a shot at the highest office in the land fall terribly short.

When I spoke to her a month after the rally, Amoruso didn't seem quite ready to make that argument. "I think we could have done a better job" at incorporating the political climate more into the Girlboss Rally, she said. Since the election, "it does feel often like the imperative is to throw everything you've ever wanted or everything you've ever worked for in the trash, and not post anything on social media that's remotely narcissistic. It's kind of like you're seen as like a bad person if you're focused on yourself.”

But to Amoruso, "speaking to women and doing anything for women is inherently political," including creating a one-day conference for them. And Girlboss Media, the digital media company that Amoruso has gone all in on since Nasty Gal's bankruptcy, is committing to women's personal growth. The website publishes two to three stories a day, offering advice on going vegan, trying dance fitness, nailing an interview, or dealing with "imposter syndrome."

Since the election, "it's kind of like you're seen as like a bad person if you're focused on yourself.”

Yet compare that with the rest of women's media, which — with the exception of IvankaTrump.com — has only become more political in recent years, from Cosmopolitan endorsing candidates in the 2014 midterm election to Teen Vogue's post-presidential election awokening.

Amoruso's platform isn't completely swearing off politics, she said. It'll continue to do things like showing solidarity for the Women's Strike on Instagram. But in Amoruso's founder speak: "We can't be successful and our audience can't be successful if we aren't arming ourselves with the tools and knowledge to take care of our own lives and the lives of those closest to us." Put on your own mask first.

But is it possible to enter the women's digital media sphere and find readership without a strong political point of view in 2017? It's not impossible. Girlboss Media already has advantages that most media startups don't: Amoruso's established following, a splashy first event, and a Netflix show that will only introduce more people to Girlboss.

Still, there's a cautiousness to everything Amoruso does now. She badly wants to demystify the concept of success, she said, to inspire people by sharing the unglamorous beginning (and middle) stories of successful people. But she's told her story already, and she's wary of being the face of a company after everything that happened at Nasty Gal, where she was, at one point or another, its face, body, mind, and spirit.

"I want to lead from the back, but I don't know if I'll ever really be able to choose that, given how public I already am," she said. "I'll throw everything I have at anything that I am building, but again, I don't want the business to be about me.”

She's even distanced herself from the term Girlboss. While she coined and wrote the book on it, the subsequent Girlboss "movement" — a word Amoruso has used in the past but tries not to use anymore — can be confounding to her. It's "something that the community has almost done more with, or the girl who's read the book or heard the podcast has done more with than I have," Amoruso said.

"I never said that I was the Girlboss," she continued. "I've never claimed to have it figured out. I've never claimed that my philosophy is superior to someone else's."

"I never said that I was the Girlboss. I've never claimed to have it figured out."

In the first chapter of her book, Amoruso describes "#Girlboss as a feminist book, and Nasty Gal as a feminist company." But for the next 200 pages, there's not a word more about feminism — no advice on incorporating feminist values into business.

And so it was surprising, after the publication of #Girlboss, that Amoruso, so uninterested in "sitting around and talking" about feminism, came to represent feminism for so many. A book that was never meant to be a feminist text became one. Amoruso's audience, the ones who adored her and the ones who reviled her, turned it into one. And why? Because as feminism became trendy, more young women were hungry for feminist mentors, and there just weren't that many around.

"I'm one of the most public female founders that have made it, I guess, as far as I did," Amoruso told me. "There's fewer of us to point at."

So Amoruso went along for the ride. And now, after she's lost much of what she spent 10 years building, she's still the inventor of an identity that millions of young women claim.

But these could be the last of the Girlbosses. Girlboss Media, the company, could thrive and grow, along with Amoruso's fame and fortune. But the women who are now of the Trump generation — the marchers, particularly the youngest of them — will find another identity to claim, one that is reflective of these troubled times, one that is not attached to a complicated woman who never really asked for this, one that is not trademarked by a business, but belongs more to the people. Could it be "feminist"? ●