Abuela takes out a ziplock bag full of neatly folded dollar bills. I am 9 years old. My sister, my cousins, and I crowd around her with outstretched hands, begging like baby birds. La panadería has just opened its doors. That’s the best time to go, Abuelo says, because everything is fresh.

The little bakery is an explosion of colors and sweet smells. There are pink, yellow, and vanilla conchas. There are beautifully browned elotitos and orejas, glazed and powdered to perfection. There’s a scratchy speaker perched in a corner of the ceiling, doing its best to play a Spanish radio station.

“¡Buenos días, Dallas!” says the DJ. He proceeds in rapid-fire Spanish, way too fast for me to understand. But when the next song starts, I recognize it right away.

“La bidi bidi bom bom!” Selena’s voice competes with my abuelo’s. He’s chatting with the woman in the hairnet and floured apron behind the counter. I don’t catch a word they’re saying, either; the vigorous cadence of Chicano Spanich has always intimidated me. “Bidi bidi bidi bidi bidi bom bom!”

It doesn’t get much more Tejano than this shit right here — standing in a panadería, surrounded by pan dulce, with Selena Quintanilla playing on the radio. These are the textures, the smells, and the sounds of the barrio.

My abuelos are poor everywhere but here. Here, everything is a quarter, or two quarters, or a dollar, tops. Abuela takes a dollar bill from her ziplock bag. “Mijo,” she says. She motions me closer. She proudly stuffs the bill in my palm and closes my hand into a fist. I wonder if this is the grandmother she’d like to be all the time, la abuela who spoils her grandchildren.

“Go ‘head,” she says with a rare, toothy smile.

I grab a plastic bag, and briefly, the world is mine. I pick out a yellow concha, and then a puerquito, and it seems to me that I could stuff the whole bakery into this bag and walk out with a nickel left in my pocket.

“Bidi bidi bom bom! Y se emociona. Ya no razona. Y me empieza a cantar, me canta así. Bidi bidi bom bom!”

We cram into the car, our plastic bags bulging with sweets. The yellow sugar of las conchas collects in crumbs at the bottom as we drive through the barrio, on our way back to auntie’s house in the suburbs.

My abuelo has a cassette tape with mariachi music and Selena songs. I’m so used to hearing Selena’s songs that, even though I don’t speak Spanish, and even though she’s been dead for five years, I know every word to “Baila Esta Cumbia” and “El Chico del Apartamento 512.”

Selena knows all kinds of things about me before I do.

Before I know how to string a sentence together in Spanish, I sing Selena. Before I even know that I’m gay, I sing about el chico del apartamento 512. Selena knows all kinds of things about me before I do. Abuelo plays the tape, and we all sing along, and when it’s done he says, “Play it again, Sam!” and flips it over.

My abuelos are from a Texas barrio like this one, but I feel like a tourist in my own skin whenever I visit. I live in Oklahoma. I speak only English. My mom is brown, and my dad is white. I am not poor like my abuelos. I am not “Mexican” in the way that they are “Mexican.” Pochos is what we’re called — people of Mexican descent living in the United States who don’t speak Spanish.

I understand that my roots are here. My abuelos are always taking me to Texas with them, and wherever we go, be it Dallas, Wichita Falls, or San Antonio, we always go to the barrio, and the barrio always looks the same: like an in-between mixture of Mexico and America. A “both,” a “neither,” a “nothing.”

That’s sort of how I see myself, too — as incomplete. A mixed person; a “half” person. Sometimes people ask me, “What are you?” like I’m some sort of rogue science experiment, and I don’t have a solid answer to give them.

I go without answers until I’m a college student, and I discover that someone has actually written about this identity crisis, and about the Mexican-American twilight towns I remember from my youth.

“The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta (an open wound),” wrote the lesbian Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa, “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds emerging to form a third country — a border culture.”

It is Anzaldúa who gives me a word to define my identity crisis: “Nepantla,” which means “in the middle of it” in the Aztec language Nahuatl. It is the state of in-between-ness that Chicanos inhabit. It turns out I’m not alone in questioning my authenticity as a Mexican-American. In fact, identity crisis is a hallmark of my people.

There’s a line in Selena, the famous 1997 biopic starring Jennifer Lopez, that also sums this up well. It’s delivered by Edward James Olmos, who plays Abraham Quintanilla, Selena’s dad. (Olmos also happens to play Jaime Escalante in the other staple Chicano film, Stand and Deliver. According to Hollywood, there are, like, five of us.)

“We gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans,” Abraham says. “Both at the same time. It’s exhausting. ”

Selena Quintanilla-Peréz was born in Lake Jackson, Texas. She moved to Corpus Christi after her father’s Tex-Mex restaurant failed and they were evicted from their home. She grew up in a poor Latino community and performed with her siblings at quinceañeras and weddings.

Like me, Selena was a pocha. She wasn’t brought up speaking Spanish at home, something I had always essentialized in my idea of Mexican-American identity. She didn’t hide the fact that she was trying to learn, either. In her Spanish-language interviews, she would often mess up, and she would just smile and laugh and keep on going.

When I was a kid, Selena was omnipresent. She was the background music of panaderías and Michoacana Meat Markets and sweaty road trips to Texas. But as I got older and I found myself in those places less and less, she stopped being a constant and became more of a relic, a reminder of my childhood.

I thought that was what being a Mexican-American was about: losing the Mexican to become the American.

I saw my Mexican-American identity in much the same way. Sure, those were my roots, but I had transcended them. I went to a mostly white college where I was treated as a (mostly) white person. I saw my relative comfort, compared with my abuelos’ struggles, as a completion of the great assimilationist mission they had passed on to me. I thought that was what being a Mexican-American was about: losing the Mexican to become the American.

In the Anglo world, the success of the Mexican-American is measured by how much we are able to forget. Our language and our customs are impurities that must be sieved out. To the Anglo mindset, the barrio, with its communal plazas and its bright colors, is not perceived as a genuine expression of a unique culture, but rather as a desperate clinging to an old one. This mindset holds that the barrio is why we assimilate so slowly, because we insist on carrying our homes on our backs like turtles, burdened and encumbered by them.

I bought into this mindset, for years, and it made me feel like a knockoff. It made me feel like my culture was borrowed, that we were a hodgepodge of cheap imitations of the Mexican and the American. But the more I learned and the more I read, the more I realized that what I thought was transcendence was actually shame. That I had been conditioned to view my Chicano roots as lesser, as a burden. And that’s when Selena came back into my life.

Her music was Tejano, Tex-Mex — our music. But most importantly, both in her music and in her aesthetic, she represented a bold, full-bodied embrace of our culture. Selena twirled across a stage in hoop earrings and a purple jumpsuit and then danced the cumbia, and millions of people loved her for it. She defied the parameters for success that American whiteness has established for Mexican-Americans, and in turn her success shattered boundaries.

When I listen to Selena, I feel like a whole person.

When I listen to "Baila Esta Cumbia," I hear la panadería. When I hear "Amor Prohibido," I feel like I’m in my abuelos’ car again, wedged shoulder to shoulder with my cousins and singing along, and I realize that I am not a fraction, and my culture is not an in-between. It is a world unto itself, with a people and a language. When I listen to Selena, I feel like a whole person.

Today, over a decade after her death, little kids are still dressing up as Selena. Her MAC cosmetic collection flew off the shelves in 2016. There was an attempt to bring her back as a hologram to go on tour. Fiesta de la Flor, a music festival dedicated to Selena in Corpus Christi, continues to grow in attendance every year. Selena fever shows no sign of dying down.

The fact that she remains such a prominent figure so many years after her death is a testament to her impact. It is also a celebration of the culture we share, a culture that rejects the somber Western view of death and embraces the Mexican perspective.

“The word death is not pronounced in New York, in Paris, in London, because it burns the lips,” wrote the Mexican poet Octavio Paz in The Labyrinth of Solitude. “The Mexican, in contrast, is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love.”

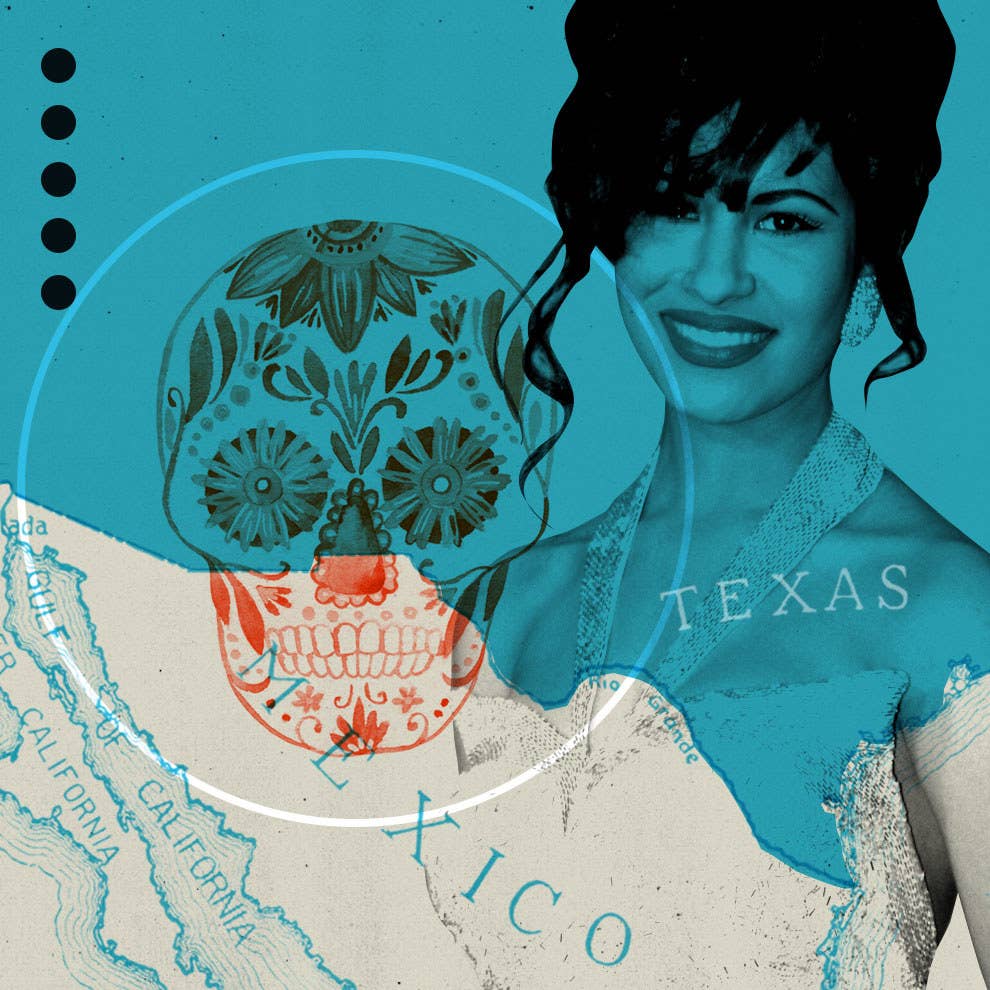

Selena was taken from us too soon. What we are left with are images of her smiling face, her iconic, glittering outfits, and the sound of her music. In this, she is the very embodiment of the Mexican concept of death, the smiling sugar skull, the joy and the tragedy rolled into one.

I am 25 when my abuela dies. I fly back from New York City to Oklahoma to attend her funeral in the Texas barrio where, years and years ago, she gave me a dollar to buy as much pan dulce as I wanted.

I sit next to my abuelo in an old wooden pew, his face buried in his arms. I am reminded that we are never more Mexican than we are in the face of death. I am reminded that, before we are Spanish speakers or Mexicans or Americans, we are alchemists. We take what little we are given, and we turn it into conchas, or into a song, or into a joke. We turn tragedy into joy.

After the funeral, I join my abuelo at a table where refreshments are being served. He’s already back to his usual self, smiling, shaking hands, cracking jokes, laughing. A relative makes his way over to us. Being Mexican means having a shit ton of relatives I don’t really know, and they’re all in this building. This man has a handlebar mustache, and slicked-back salt-and-pepper hair. He shakes my hand.

“Gee whiz,” he says to me, “from Oklahoma to New York, huh?”

“No,” my abuelo corrects him. “From Mexico to Oklahoma to New York.”

I smile. I realize that my whole life, whether I knew Spanish or not, no matter what I called myself, I have always been this. I am Chicano. I carry my home with me wherever I go.

John Paul Brammer is a writer, speaker, and activist based in New York City.