TOVARNIK, Croatia — As Croatian police tightened a cordon around the train station, Mohammad, a 24-year-old law student from Aleppo, Syria, leaned against a car and considered his options.

Alongside thousands of his fellow refugees and migrants, Mohammad, who declined to give his full name in order to avoid trouble with Croatian authorities, the official route — via bus arranged by the government to the capital, Zagreb, and then on to Slovenia — suddenly seemed less than ideal.

But the other route that many were choosing — marching off through the farms and fields around Tovarnik in search of other towns, trains, or taxis — had its own problem, a new one for those on the long migrant trail: land mines.

There are nearly 60,000 land mines scattered around the countryside of Croatia, according to the Croatian Mine Action Center (CROMAC), relics of the country's brutal war with Yugoslavia, which ended 20 years ago.

Many of those fields are near the Croatia–Serbia border, including at least two known hot spots in the vicinity of the border crossing at Tovarnik that are actively being de-mined this week. Croatian officials said they were working to speed up education efforts for the migrants.

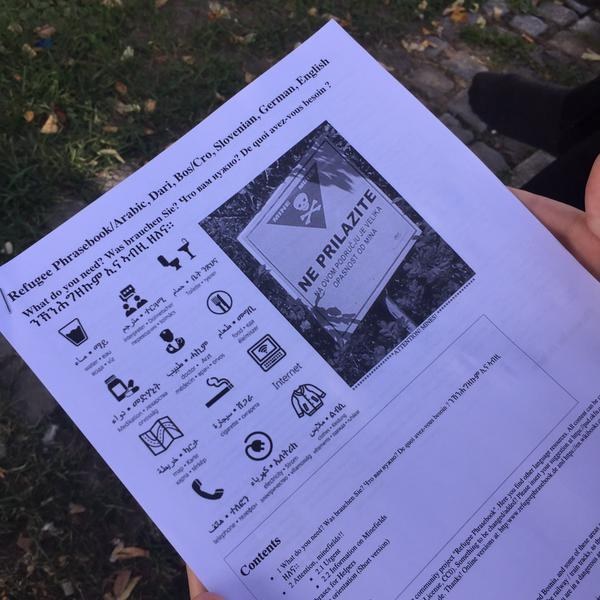

"We are aware of this situation, and I can tell you we are preparing together with Serbia some leaflets with pictures of the warning signs, in Arabic and English, and these will be distributed to them in Serbia and Croatia," said Miljenko Vahtaric, a top official at CROMAC. "So they will be aware of the areas that are affected by the mines."

Since 2012, there have not been any deaths from land mines, according to Vahtaric, and every area suspected to contain them has been cleared or extensively marked with signs.

He also said that he considered it unlikely that migrants would bother to wander through those fields: "They are traveling from thousands of miles, weeks of travel, to come to Croatia and Europe, and then to risk their lives in a minefield? I don't think that will happen."

That was on Thursday, before Croatian authorities found themselves overwhelmed by the tide of refugees streaming into their country, and before border officials started talking about shutting down the crossing points.

Advocates for the refugees, many of whom have witnessed the lengths to which many have gone this far to make it to their destinations, are less sanguine.

"It's not just the mines, it's everything that's left over," said Daniel Szatmary, the coordinator of the Hungary-based volunteer group International Relationship for Peace, referring to the likelihood that border areas also contain unexploded munitions from the war. "It's extremely dangerous around there. Right now it is playing with life, and if you're not giving enough information, people can be really injured."

On Friday, as Croatian authorities indicated they will start rerouting people to Hungary and Slovenia, dozens of refugees could be seen walking toward Zagreb along the country roads in the northeast, an area that is still heavily mined.

Croatian and Serbian NGOs have attempted to warn groups of migrants about the danger of the mines, and an informal survey of those in the border crossing area Thursday suggested that most had gotten the message, one way or another.

"I heard about it from someone in another group at the border of Hungary," said Ahmad Toubeh, a 42-year-old supermarket distributor from Damascus, as he trudged along a dirt road through the cornfields between Serbia and Croatia. "But are they around here? I heard that there were a lot of signs."

Volunteer groups also attempted to spread the message on Facebook, where many migrants get information along the way. But many of those using Greek SIM cards in their smartphones had trouble connecting to Serbian mobile networks, and it wasn't clear if they could access the internet.

One Syrian, who heard about the mine fields from a humanitarian activist, said he was "telling everyone I see" about it.

Mohammad, the student from Aleppo, had heard about it, too. "It's from person to person," he said. "I just want to make it to Germany so I can finish my studies. This is my hope, but I don't know if it will be possible."

But for the afternoon, at least, until a better option came along, he opted to wait for the buses. It didn't seem to him to be a great idea to wander off in the fields — not just yet.