Last month, Michael Thomsen, writing for The New Yorker, sketched the rise of a ubiquitous but little-discussed practice in the world of video games: outsourcing.

Video-game makers were beginning to deal with the complexity and cost of their operations by relying on outsourcing—by using both temporary workers in the United States...people in low-wage developing countries.

Game Developer Research found in a 2008 survey that eighty-six per cent of game studios used outsourcing for at least one aspect of development. In 2009, Electronic Arts laid off more than twenty-six hundred employees; the C.E.O., John Riccitiello, said the company had overinvested in internal development and vowed to increase focus on outsourcing. "The high-cost locations have gotten so far out of line that the best we can do is keep a core design team there, and use support in other places like Montreal or South Korea," he told investors at a 2009 presentation.

Game outsourcing involves delegating to studios in the global east and south a variety of development tasks, from 3D animation to character design. By far the most commonly outsourced job, however, concerns so-called "asset dumps," the thousands and thousands of static, three-dimensional objects needed to populate a massive three-dimensional world.

These objects are usually mundane — ashtrays, trash cans, debris, the things that say "Made in China" in the real world — but are sometimes quite significant. It can be hard to suss out exactly what in each game comes from an outsourcing studio, and that's by design; the point of these companies is to do heavy lifting for Western and Japanese developers without calling attention to themselves. But the Indian studio Dhruva, one of the oldest game outsourcing shops, has a public portfolio, and it reveals the nearly elemental degree to which some games are outsourced.

We took three games that Dhruva worked on, and, applying the company's own descriptions of their contributions to the games, redacted all the visual information that came from India.

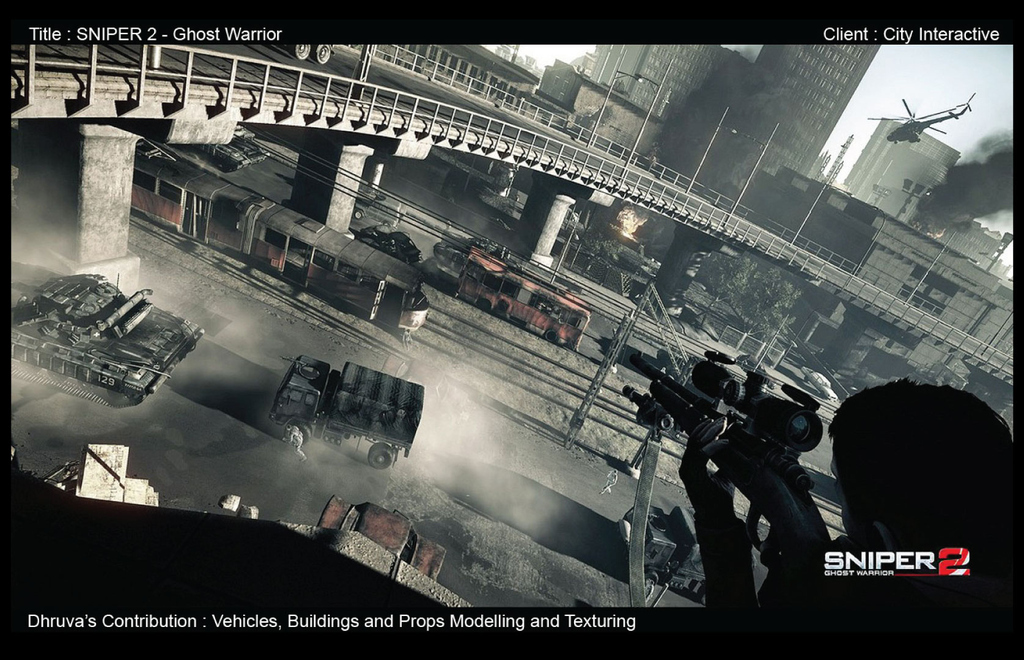

Sniper: Ghost Warrior 2 - 2013

From the Dhruva website:

Dhruva worked on environments, props and vehicles, essentially creating entire levels but without putting them together. The work was submitted in the CryEngine. Thanks City for an exciting project!

With outsourcing:

Without outsourcing:

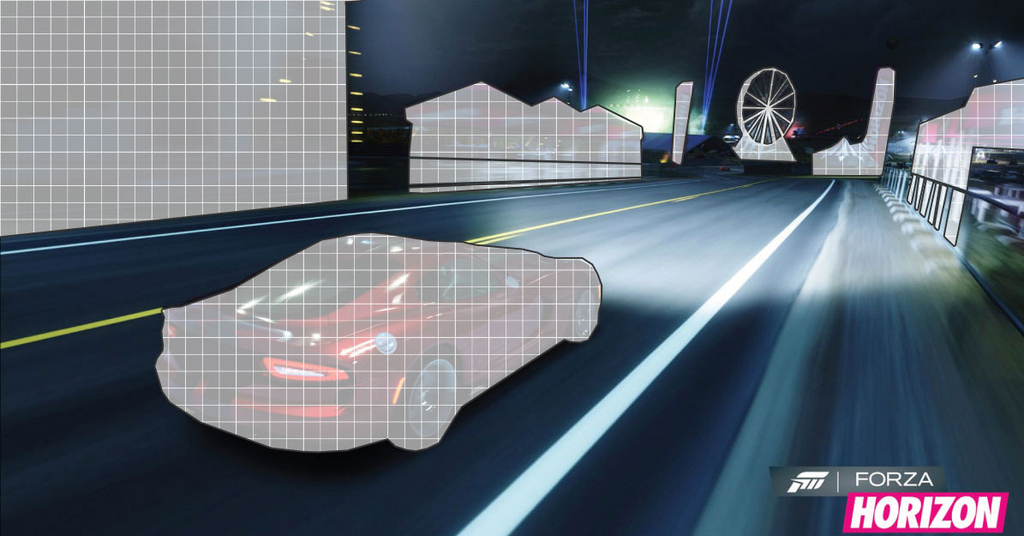

Forza: Horizon - 2012

From the Dhruva website:

Dhruva created vehicles and environements for the game. We have happy to have a chance to yet again work with the folks at T10 and meet PG Games. Check out our work in the portfolio.

With outsourcing:

Without outsourcing:

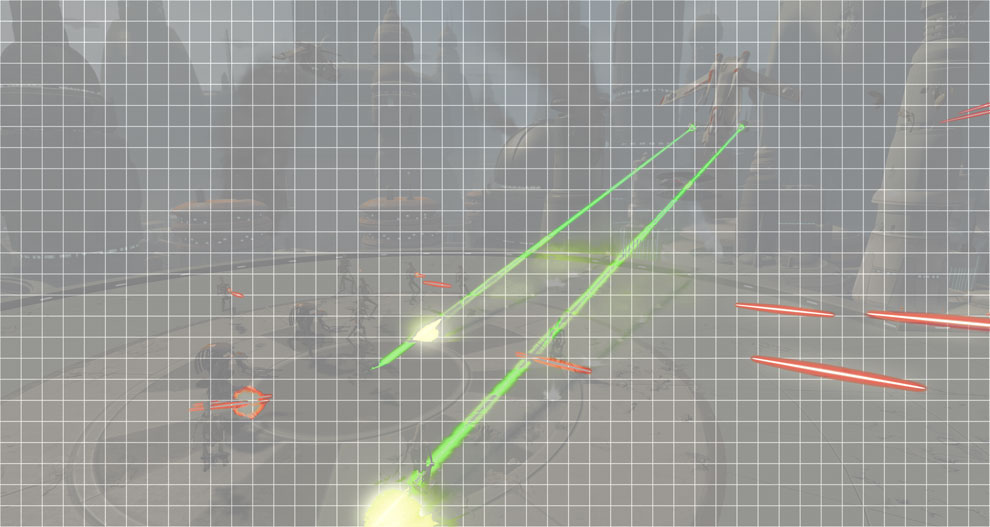

Kinect Star Wars - 2012

From the Dhruva website:

With Kinect Star Wars, Dhruva embarked on an epic journey of handling over 4000 man days of work for the project including working on full levels, environemnt, architecture, foliage, vehicles and characters. It was a learning experience for us and we could not have done it without the patient help of our friends over at TRI and MGS.

With outsourcing:

Without outsourcing

(Also, Dhruva's language is somewhat unclear. If in fact they produced the environment and the architecture, as well as the character and vehicle models, then you'd be left with, just, um, lasers.)

These three games — while AAA — may not top sales charts. But that doesn't mean the heaviest hitters don't outsource assets. As Thomsen reported, artists in Malaysia contributed work to Bioshock Infinite, and Virtuos, the Chinese giant, worked on The Last of Us. Next time you sit down with that game, consider this passage from a press release, and how your playing experience might have differed without outsourcing (the emphasis is ours):

Virtuos is proud to have created character art, environment art, and props for The Last of Us, including clothing for main characters Joel and Ellie.