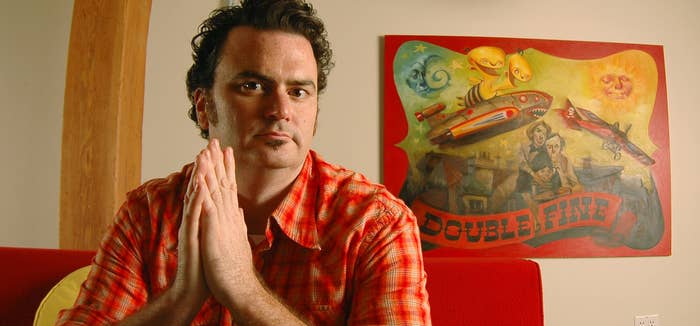

If there is a universally beloved human in the world of video games — in which strong and vituperative opinions are de rigueur and fanboy-drawn battle lines scar the corpse of consensus — that human is Tim Schafer. Schafer, 46, is the founder of Double Fine Productions, the 65-person San Francisco studio that has cultivated a public image as part game developer and part merry experimental digital art studio (in periodic "Amnesia Fortnights," the employees of Double Fine are split into groups and told to forget their current project and build new game prototypes, some of which have been turned into full games).

But Schafer is known best for a handful of games from 20 years ago: The Secret of Monkey Island (1990), which he co-wrote; Day of the Tentacle (1993), which he co-wrote and co-designed; and Full Throttle (1995) and Grim Fandango (1998), both of which he wrote and designed. These four games are all adventure games, a distinctly literary genre that rose to its highest prominence in those years behind wonderful narratives, strong characters, and sometimes painfully difficult puzzles. For the PC children of the 1980s and 1990s, these games are more than a warm memory; they hold the same imaginative power as Disney movies.

As the public appetite, and publisher financing, for these fairly low-tech titles dried up in the late '90s, Schafer continued to do great work; his 2005 platforming game Psychonauts has established itself as one of the great cult titles of all time. But his name, and his sensibility — extraordinarily funny but also sweetly sentimental — will always be linked to the adventure genre.

Yesterday, Double Fine released the first act of Broken Age. It's Schafer's first adventure game in more than 15 years, and it comes at a time when the gaming public, armed with iPads and Kickstarter links, has rediscovered their love for the genre. We talked to Schafer about his new, crowdfunded game, and about the pressure he felt trying to live up to his reputation as one of the fathers of the genre.

Why did you decide to do another adventure game?

Tim Schafer: Adventure games are something I made a lot in the '90s and a lot of people liked them, but the industry turned away from them for whatever reason. But a lot of people still like them. People would contact me and say they wanted another adventure game, and I would point out that publishers wouldn't really publish them because they couldn't make much money there.

But fans would always say, "I'll buy a copy!" And I thought, if only there was some way for all of these people who would buy one copy to get together and fund the game! And then Kickstarter shows up and allows people to do exactly that thing. It's pretty amazing. All these people with just $35 managed to fund this game by themselves.

Do you think if it wasn't for crowdfunding you would have ever made another adventure game?

TS: I really don't think so. It would be hard to find someone who would take that kind of risk with their money. There is a wide-held belief that you can't make money with an adventure game. We could never get it funded. But Kickstarter made it possible.

After working for years on games with increasingly complicated mechanics and player movement, how did it feel to go back to a style of game that is known for rigid restrictions on player freedom?

TS: Well, for one thing, I would have felt very nervous if I was taking a risk with someone's money and just doing that — what if that kind of gameplay just doesn't resonate with people anymore? That's what was different about doing it with Kickstarter. All these people told me in advance they would love this kind of game, so that sort of took the risk away. It was nice to know I was making a game for a built-in audience of people who I knew were there.

The adventure genre has always been known for having crafted storylines. So if you're going to make an adventure game, you have to put the extra effort in to make that storyline worth it, so players don't even notice that they don't have as many choices as they would in another game that is all about choosing your path, like Heavy Rain. If you're going to provide one path, you have to make it feel like the most rewarding path. There's an art to that, and that's what we worked really hard to perfect in the '90s and that's what we tried to do with this game.

Were there things you'd forgotten about working in the genre that you realized you had missed?

TS: It's nice to work in a genre where you can focus really heavily on the narrative. There aren't that many genres that put character and story first. That sets the mood, and the music, and the art, and all that. That all helps to immerse the player in the fantasy world. I really enjoyed going back to that and thinking about, what is an interesting story that I can tell here that I couldn't tell in any other genre?

You're one of the most important people in the history of this beloved genre. Did you feel pressure to live up to that reputation while you were working on Broken Age?

TS: Definitely. I felt like a lot of eyes were on this project. I knew that it had to be good. That's OK — that's the pressure you feel no matter what, and in this case those people are the ones funding the game, so all you have to worry about is whether adventure-game players would like an adventure game.

Your games may not test hardware, but they are always so uniquely stylized that they look just as good 10 years down the line as they do when they come out. If you play Grim Fandango now, it looks like a game that looks, well, exactly what the creators wanted it to look like. Was that part of your consideration when you thought about what Broken Age would look like?

TS: We always had a desire from the beginning to make things that hadn't been done before and that really stood out. I really believe that games are art and everything that you make should be an individual statement that no other person or team could make. I really hope we made a game that when people play it, they feel that only Double Fine could have made this game.

The important thing is that each game is a really specific artistic statement. In this case, it was inspired by the work of our lead artist, Nathan Stapley. We've worked with him since the beginning, but his art is usually hidden from the player, because it's concept art. But 2D graphic adventures allow you to put 2D paintings right in front of the player as the final asset. I really wanted a game where Nathan's unique art style could really stand out front and center.

The game is very funny, but the humor is different than your older games. In those, the humor feels punch line–driven — there's a joke in every line. In Broken Age the humor feels more story- or character-based. I was wondering if and how your approach to humor in games has changed over the years.

TS: I've lived more since I made those games. I hopefully have a deeper empathy for other people — I think we all do as we get older — and that maybe shows in the treatment of the characters in the game. I've always had a hint of [heavier] topics in my games. Grim Fandango has people meditating on the nature of death. Psychonauts dealt with people's sad and hidden memories. I've always tried to deal with the whole spectrum of the human experience. And I think that just makes the funny stuff funnier if it's in the context of the whole human situation.

The adventure game is in the middle of a surprising renaissance. That has to do with a lot of factors — digital distribution, crowdfunding — but I wonder if you think there's a human or cultural factor there? Is there something about this moment in time that is conducive to the genre?

TS: In some ways I think it's really a business thing, which sounds more calculated than you might expect. But the nature of funding and creating art is changing in every entertainment industry. People are using crowdfunding and more creative ways of structuring things so that large companies don't control everything and individual artists are making individual statements. I think that has the effect of allowing things to exist that didn't exist before. Like a game that was maybe considered in a niche genre could be brought to the fore because artists have more control and more access to funds.

Which of the newer adventures games have stuck out to you?

TS: When I started this project I was playing Machinarium and Swords and Sworcery, which are different takes on the genre, different branches on the tree. Also The Walking Dead and Gone Home. It's great, because no one is saying there's just one way to interact with a character or a story. There's all these different ways and people are trying their own unique twists. And that's healthy for the medium as an art form.

Have you ever thought about writing for any other medium? Books, or comics, or movies?

TS: Every writer thinks about an idea for a children's book or a screenplay or all these different things. It's just that games are so much more interesting to me. I've loved games since I was a kid, and you can do so many cool things that you can't do in any other form. I think it would be fun to do those things someday, but right now it's too exciting to explore the world of games. Games are cool!

What were the inspirations behind the story of Broken Age?

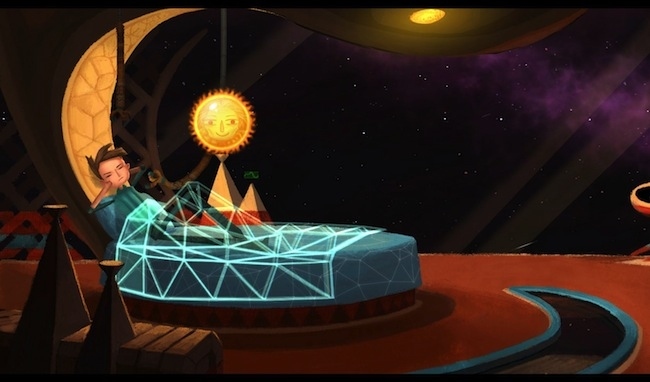

TS: It's about two characters — Vella and Shay — who are 14 years old and are in these crazy different worlds. She's living in a pastoral village and he's out in outer space and they seem completely opposite of each other, except thematically they are dealing with similar situations. Lives have been prescribed for them and they are starting to push up against the boundaries of that. All their lives they have believed certain things and participated in certain conditions and now they are starting to ask, "Do I really want to do this?" And they are struggling to break free, and the player helps them.

I was playing the game right after I saw the movie Her — I don't know if you've seen it, but I felt that Her and Shay's story are totally of a piece. They're both about young men whose lives are totally modulated through and controlled by technology.

TS: I've always liked stories like that. Did you ever see Silent Running? That and Moon. That idea of solitude and being surrounded by technology — that's a modern feeling that a lot of people have.

And then with the Vella story, that felt like folklore, or a fairy tale.

TS: I have a daughter and I read a lot of fairy tales to her. And seeing some of the choices that are presented to the girls as opposed to the choices I would hope for her to have in her life, that's a recurring theme. I think about it every time I'm reading her a book before she goes to bed. And so that, and also she loves princess cakes, which show up in the game.

How will you define success for Broken Age?

TS: We've already succeeded! We succeeded the moment we had that Kickstarter. And 90,000 people came forward with their money and said we love this kind of game and we trust you to make it. It was success from that moment on. Now I want to fulfill that promise. A lot of things about Kickstarter are new, and a lot of people think it's a Ponzi scheme or something. So I really long to finish the second part of the game and have everyone know that we weren't joking around and we're not going to run off with people's money.