Earlier this week, I played about 30 hours of a new Japanese video game called Dark Souls 2. It had an effect. My state of mind on Wednesday night when I switched off the PlayStation 3 was not what a neutral, third-party observer would call "good" or "normal," not that I would have allowed another person into my home at the time to witness the creature I had become. You see, the Souls games — this one being the third, confusingly — make things happen to your body that are nearly identical to the things that happen to your body before and during the big, real-life terrors: toasts and interviews, dates and swim tests. I was, to put it straight, a mess. My heart was racing. My head couldn't hold a thought. My hands were not quite, like, shaking, but definitely not still either. I think they were technically…vibrating? And, ah, well, reader, I: was sweating. Not sweating as in, rivers or streams or anything with the healthy properties of movement. I mean the stagnant, clammy, patina of shine kind. I mean the locker room kind. There were some pheromones in the air, is what I'm trying to tell you.

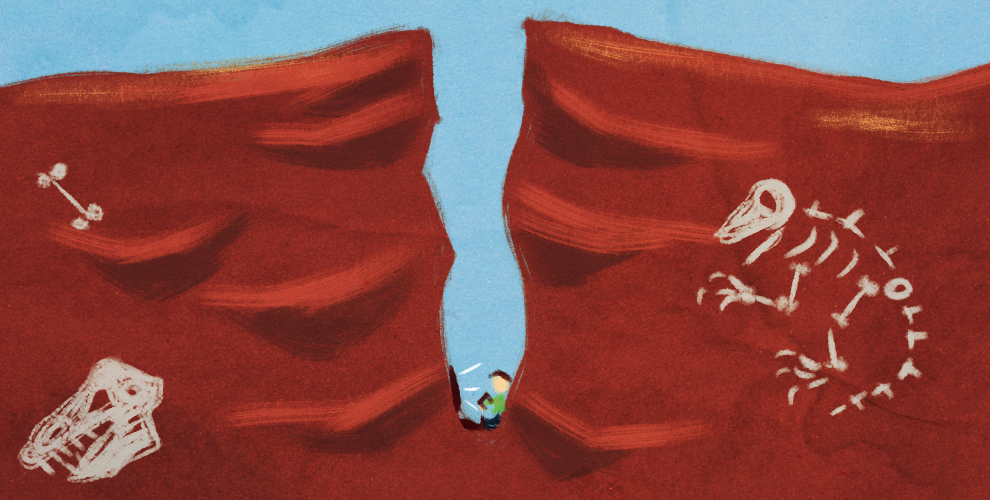

The Souls games are as well known to gamers as they are obscure to the laity, so I'm aware that many of you will be wondering what kind of game has the power to reduce a 29-year-old job-having human to the quivering sum of his fight-or-flight reflexes. I will tell you exactly what kind. Imagine any three-dimensional iteration of The Legend of Zelda, the classic game with the indefatigable elf who runs around a big fantasy world discovering buried treasure, plumbing dungeons, and thwarting evil. Well, you spend most of Dark Souls 2 doing just that: running around a giant fantasy world with a dumb name (Drangleic), opening chests to find weapons that would make funny nicknames for your genitals (Manslayer; Witchtree Branch; Black Scorpion Stinger; etc., etc.), and using those weapons to kill monsters. OK, but, here's the difference: Imagine The Legend of Zelda set entirely within the Red Wedding. Imagine Zelda and Link et al. being brutally, graphically murdered, over and over, and there's nothing you can do about it.

Now you've basically got it: The Souls games are like 50-hour playable Red Weddings in which you are the victim.

These are, to put it mildly, games in which you die. The marketing slogan for the first game was "Prepare to Die." The jokesters at From Software, the Tokyo company that makes Dark Souls, have put in the new game's central hub an obelisk on which is written a constantly updating count of the global number of deaths. As of last Wednesday night, the count was 4.3 million. The game came out on Tuesday. I would say I'm about a third of the way done.

To hear the sages of Reddit tell it, the reason these games are so good is simply because they are so difficult, in a way that is specifically "old school" and "the way games used to be." But that's not adequate. I mean, I bet the sense of satisfaction you get if you escape from a kidnapping is pretty epic, but that doesn't mean the experience of being kidnapped is great. The thrill of getting past something unpleasant isn't proof that we should do unpleasant things. More to the point, it sets the Souls games up as some macho crucible of gaming skill, and we've got Modern Warfare multiplayer for that. And frankly, there are a lot of maddeningly hard games (many of which owe their existence to the Souls games), and none of them have captured the gaming imagination the same way. No, the reason these games are, to my mind, the most important, memorable, haunting games of the past 10 years is not just because of their difficulty in relation to other games. Simply put, they have made me aware of the crushingly passive way I consume games — and the way I think we're coming to consume entertainment in general. And for that, I both love them and hate them.

Look, let's just be honest with each other. You're skeptical. You sense that I'm about to make the argument that a series of little-known Japanese role-playing games, the kind with dragons and enchanted swords and health potions, is culturally significant. And, let me be the first to say that your skepticism is understandable, even justifiable. It comes from the way we think about and talk about games, especially the dorky ones, and I feel it too, all the time. It's there. I'm not denying it. So how do I gain your trust?

Start with this: Anyone reasonable is willing to acknowledge that certain games have certain kinds of cultural significance. Some games, Pong and Tetris, let's say, are culturally significant because they have historical importance. Some games, Mario and Zelda, for example, are culturally significant because they have been claimed by pop culture. Some games, like Halo, are culturally significant because they sell a lot of copies. And some games are culturally significant — especially the Grand Theft Auto series — because they engage so obviously with the zeitgeist that they can't be ignored.

What we haven't really been willing or able to say, outside the limited scope of the personal essay, is that a game is culturally significant because it changes our perceptions of the world and our understanding of our lives. In other words, we haven't really had a game yet that the culture at large is willing to grant the cultural significance of a mass-market piece of narrative art, like, I don't know, The Wire, or The Goldfinch. There are a lot of reasons for that, but I think the main one is an abiding, low-level embarrassment about the content of games and our social judgments of the people who play them. That's fine. A lot of games and a lot of the people who play them are waking nightmares. (So, for that matter, are a lot of television fans.) Anyways, what we really seem to be saying, in that judgment, is that only certain forms of media are worthy of rearranging our neurons (or our souls, if you prefer) in a meaningful way. That's a feeling, not an argument. So what we're ultimately left with is simply an intuition that games can't be profound in the same way as other media, and to that I would say: Take a long look at other media.

I'm serious. The Souls games don't exist in some vacuum of taste; they are cultural products in the year 2014, and I think it's important to understand the state of the culture in which they are consumed, especially if you are going to be nice and let me try to convince you of their massive importance. Right, so: The master trend of consumer entertainment in the developed world in the 21st century is accessibility — ease of use. For paltry amounts of money, humans can buy unlimited access to caches of film, television, books, and music so vast that they feel less like a series of products than a single promise. The promise: You will be able to be entertained how you want, when you want, where you want, if you want. The CEO of HBO told BuzzFeed earlier this year that his company's mission in creating HBOGo is to create video addicts, and that's just the point of the on-demand entertainment cloud. It's a promise to a culture of junkies that the fix will always be there.

And what exactly are we using? How has the content changed? Well, there's more of it that seems "good" than ever, to the extent that even the paper of record has taken notice that there is something mysterious, even unnerving about the quantity of "must-watch" television being created. Surely part of this perception has to do with the mad proliferation of opinion on the internet. But something about our entertainment now seems suspiciously palatable; reverse-engineered; eager to be liked; ingratiating; easy.

This trend in consumer entertainment feels profoundly of the internet, that crowdsourced, customer service medium, the guiding question of which, as Paul Ford wrote, is, "Why wasn't I consulted?" And it seems obvious to me that this ethos has seeped, through crowdfunding, through consumer data, and through the instant feedback of social media, into the things we watch and play. Technology finally allows humans to exert influence on the creative products they buy, and boy, we are not shy about it. We're being consulted now, all the time! Look at the things we've done! We resurrected Arrested Development! We paid for a sequel to Garden State! We turned Rizzoli and Isles gay (maybe)! We put a black character on Girls (for three episodes)! My point isn't that this is good or bad; my point is that our entertainment is becoming, more than ever, couture, micro-targeted, an ever-improving two-way recommendation engine — the endpoint of which may finally be a custom television show for every person on the planet. Everyone with a bank account will be consulted!

But hold on. With all due respect to Zach Braff and Paul Ford and web two-point-whatever, gamers invented "Why wasn't I consulted?" Gamers, those petition-filing, hair-splitting, petty pioneers! A group of people who got one of the world's largest corporations to walk back major facets of a $500 product months before its release simply by being cranky. I would wager that no entertainment in history actively panders to its micro-audience as much as the modern video game. Take Titanfall, the new, ballyhooed shooting game for Xbox One, which came out on the same day as Dark Souls 2. This thing is a freakishly sophisticated campaign to unite various gamer micro-constituencies; it could teach Congress a thing or two. I can almost see the deck at the pitch meeting: "If you like Military Shooters or Giant Robots or The Near Corporation-Owned Future or Parkour Movement you will love Titanfall!" Online shooting games had been getting too hard; this was a problem and people were complaining. Titanfall added computer-controlled characters who are easy to kill, so newcomers won't ever feel too bad about themselves. Again, I'm not saying that's good or bad, just that gaming has been and will be at the vanguard of the entertainment feedback loop. We were consulted.

But then there are Demons' Souls, Dark Souls, and Dark Souls 2, standing athwart contemporary popular entertainment, whispering, "Die!" They have never consulted anyone. They are as prickly and cryptic as an old recluse; they're the Emily Dickinson of video games. The first thing you see in the new one is a hooded crone who tells you, basically, "Fuck you idiot, put another game in the PlayStation." There is no instruction manual. The menus are as hard to parse as a diary in another language. The game isn't eager to let you get to know it, but it is eager to troll you. The first time you die in Dark Souls 2, you get an award. An award! It's called "This Is Dark Souls." It has a wicked and absurd sense of humor. In the game's optional tutorial, there is a mysterious coffin. I got inside it. Nothing happened. Ten hours later, while changing my character's clothing, I discovered that he was now a woman. For a moment I thought it was a bug; I've been conditioned by other games. Then I thought: Dark Souls. What is everything I have ever done? Oh, yes: the coffin. I went back and got in, and stood back up without breasts.

Dark Souls 2 and its predecessors are hard for three main reasons. The first is that in every new area you encounter, starting with the first, every single enemy can kill you in one or two blows. The second is that every time you die you lose all of the accumulated currency that you can use to make your character less susceptible to dying. The third is that every time you wish to spend that currency, you have to backtrack to a place that automatically resurrects everything you have, with your heart in your throat, killed. Basically, the Souls formula is to put a very difficult boss at a very far distance from a checkpoint with many difficult enemies in between who come back to life every time you save or die. It's devious.

If you could plot the emotional trajectory of the average player of any game in this series, it would look like a murderously volatile stock market. There are three to five "crashes" in each game where you just sort of laugh to yourself and go, "Nope: impossible!" The games are fond of the "another one!" surprise, in which just as soon as you start to get the hang of a really wretchedly difficult boss who has killed you many times, out trots another one! And yet, it's in the dozens and dozens of run-ups to these impossible situations that the game is really played. You start to talk to yourself: "Here's what I'm going to do this time." You lose track of everything going on around you. You scour every niche of the game world for something that can help you. Your motor reflexes start to sharpen.

And then something else happens. You start to feel awake, alert, as if coming out from under the influence of too much NyQuil. Or, to borrow the metaphor of the HBO CEO, it's like you finally kicked an addiction — an addiction to the slow drip of half-amusement. That's the plunging stock market: your withdrawal. After 20 hours or so, you even out. You don't fear the game as much anymore, and because you aren't as anxious, you play much better. As you replay sections again and again, you start to notice the aesthetic sophistication of the people who built the world. Every foe is worthy of a Guillermo del Toro film. Every structure is worthy of the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings. Yes, it's a fantasy game. But I mean that in the most terrifying, sublime sense of the genre. There is nothing rote about the way it looks.

Finally, as you come close to beating a Souls game, you simply feel a deep appreciation toward it. You realize that on the subject of itself, the game's designers are the experts — they know what's best for you when it comes to the game they made. Before the release of Dark Souls 2, From weathered a gamer tantrum revolving around the idea that the new game would be less demanding than its predecessors. Gamers were literally afraid that other gamers — the less hardy ones — would be listened to. The game's producers kept saying: Trust us. And guess what? They didn't consult us. They didn't pander to us. They refuse to let us play their creation half-awake. And you will want to hug them for it.

In 2006, during a study-abroad year in England, I took a semester-long seminar dedicated to Ulysses. We moved slowly and methodically, reading one section of the great book every week. At some point I was up in my professor's office hours, talking about a presentation I had given on the Laestrygonians episode. He was young and Northern Irish, with dyed blond hair, and sometimes we'd see him at concerts around London. I noticed he barely had any novels in his office, and asked him why. "Ever since I read Ulysses," he said, "I never really wanted to read any other fiction." Joyce's book had so challenged him — and yet so rewarded his persistence — that he felt let down by everything else he read.

Ask anyone who has played through and beaten one of the Souls games what it felt like to play another video game in the weeks afterward. They feel minor, silly, unserious — a stupid hobby. I haven't thought the same way about most big console games since I first played Demon's Souls in 2010. At best, they feel like amuse-bouche.

Yeats famously wrote that "The fascination of what's difficult / Has dried the sap out of my veins, and rent / Spontaneous joy and natural content / Out of my heart." His subject was the modernist preoccupation with formal difficulty, and the way it had limited his imagination as a poet. Every time you die in the Dark Souls games, you lose your humanity and turn into what the games call a "Hollow." You become green and sunken; dried out and sapless. It's a wonderful visual metaphor for the act of playing Dark Souls itself, and for the accommodation that people have always had to make to approach difficult art — books, films, records, games, etc. You set aside your subjectivity, your spontaneity, your humanity, and you accept a rigorous method. In exchange, you gain access to something genuinely new; some knowledge, some way of seeing the world and your place in it. At the end, you get back your perspective, made better. You will look differently at "natural" content, I guarantee that.

As you play a Souls game, if you're online, you frequently encounter ghostly forms moving through the world. These are other actual human players. You are watching other humans set aside their lives and go about the same great challenge as you. You can see them die, learn from their mistakes, and sometimes help them or be helped (or hurt) in even more direct ways. You quite literally gloss the game for each other, explore its meaning together, pick out its nuances. It's like one giant, mostly egoless seminar for an incredibly difficult text.

Over the past few days, I've been asking friends and co-workers to think of contemporary entertainment — books, movies, television shows, records — that are both mass-market and require an extraordinary amount of dedication, of patience, of attention. Some of the usual suspects came up: 2666, Twin Peaks (hardly contemporary), Yeezus. And yet none of these feels right. The way the devoted move through the Souls games is so granular, so slow, and so rigorous, that it feels nearly academic. And maybe that's the best way to think of the people who really submit to these games: They're like the Ph.D. students of gaming, and they pay for the privilege. They've removed themselves from the feedback loop of contemporary pop culture in the pursuit of a rarer pleasure.

And how remarkable is that? Right now there are thousands and thousands of humans who are actively struggling, together, with a piece of art that flouts every impulse of our entertainment culture in 2014, on the suspicion that rigorous engagement with a cultural product can yield enormous rewards. And for that, it might even be worth breaking a sweat.