The party on Eldridge Street could hardly be contained: Bodies spilled out of the front door onto the sidewalk, and joyous screams echoed from the roof. Inside, under the wood beams of the $7.5 million carriage house, a DJ played techno for a young and queer crowd. Amid throngs of twentysomethings who were pierced and shorn in unusual places, a performance artist named Crackhead Barney roamed around in a Trump mask, breasts bared, past a man painted green from head to toe, wearing only a jockstrap and an alligator headpiece, shut inside a dog kennel. Over the sound of a jazz band, the screams were now clearer:

“This is being paid for by Peter Thiel!”

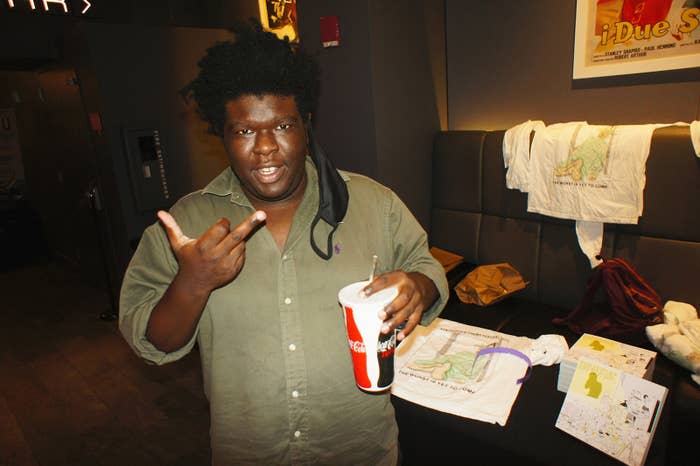

At the center of the pandemonium was a young artist from Miami named Trevor Bazile. Dressed inconspicuously in a baggy hoodie and jeans, he raced from conversation to conversation, stopping along the way to pluck at a stand-up bass and then to bounce around an art installation set inside a children’s blow-up castle.

Why Bazile wanted anything to do with Thiel, the billionaire venture capitalist, pro-Trump political donor, and magnet for liberal fear and loathing, was in one way very simple. Bazile was the creative director of the New People’s Cinema Club, a controversial film festival, and Thiel helped fund it. The Oct. 22 party, organized by Bazile and officially titled “There’s Some Hoes in This House,” was the exuberant high point of the four-day event, held at venues around downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn last fall.

Why Thiel wanted anything to do with Bazile, a queer Black experimental filmmaker who supported himself by scooping ice cream, is less obvious. Known for his support of political candidates who deny the legitimacy of the 2020 election, Thiel makes investments that can be seen as part of a sweeping project to upend the American liberal democratic order. This makes him a somewhat unlikely benefactor of a niche event designed for a small set of New York cool kids.

A chaotic mix of short films, live interviews, art pieces, poetry readings, and dance parties, NPCC brought together respected independent filmmakers, hard-right software developers, leftist DJs, and queer performance artists. It built buzz through a new downtown media scene that revolves around a handful of interlocking podcasts with provocative politics. (The hosts of Red Scare, the most popular of those shows, interviewed legendary cult filmmaker John Waters on NPCC’s first night.) The fest’s aesthetic was one of deliberate bad taste — official T-shirts depicted the Statue of Liberty dead from autoerotic asphyxiation, with the tagline “The Worst Is Yet to Come.”

But in 2022, bad taste carries a political charge. The NPCC acquired a derisive nickname during its planning: the “anti-woke film festival.” In part, that’s because rumors of right-wing funding swirled around the festival in the months leading up to it. But the label reflects something trickier to define, a broader sense that there is a core of young artists and trendsetters in New York and Los Angeles who, post-Trump, are rediscovering the desire to shock liberals. Call it, if you must, a vibe shift: a new generation of internet-native tastemakers — like many of the people crowded into Bazile’s party — who find the moralistic gatekeeping of millennials all a bit passé.

A youthful subculture that rejects liberal pieties naturally excites the American right. It’s a sign of the pendulum swinging, a chance to break the culture war stalemate of the Trump years. Thiel, who did not comment for this story, has called identity politics an “insane distraction” and a “monster” that weakens the United States. An investment in a culture of cool that declares “wokeness” unfashionable, like an investment in politicians who attack the teaching of critical race theory in schools or an investment that steers kids away from college, is a way of disconnecting the next generation from the power grid of contemporary liberalism. It’s a kind of disruption.

“This is being paid for by Peter Thiel!”

But the allure of such a shift stretches beyond MAGA Republicans. There’s a diverse coalition of Americans who resent the progressive flank of contemporary culture. It includes disgruntled liberals who think aspects of #MeToo and the racial justice movement are excessive or cynically self-promotional, media figures who have built lucrative careers banging on about “cancel culture,” and artists and writers of previous generations who find the current cultural constraints intolerable.

"Transgressive organizations like the ‘New People’s Cinema Club’ must survive because they help keep devious ideas near and dear to the hearts of the young," Waters wrote in an email.

Self-aware and supremely ironic creatures of the internet, some among this “postwoke” set understand that they are useful to the right and even joke about it. Bazile knew he had been cast for a part in someone else’s vision of the future. But he accepted the role because he saw in it the chance to pursue his own radical creative agenda — a dynamic nearly as old as art patronage itself.

After the NPCC, a meme went around that depicted a large puppet, labeled “Trevor Bazile,” holding a smaller puppet, labeled “Film Festival,” which in turn was holding an even smaller puppet, which was labeled “Peter Thiel.” The image has a knowingly absurd implication: that an unknown young filmmaker, of all people, could manipulate an oligarch who is known as a right-wing puppet master. But it also contains a more complex truth. For Bazile, who above all was aware of the way he was being used, Peter Thiel’s money was an opportunity to build a new space in the rubble of American culture.

In 2007, film programmer Hadrian Belove founded Cinefamily, a repertory movie theater in Los Angeles. Playing a mix of strange, forgotten, and contemporary films, the theater quickly turned into “an epicenter of young Hollywood,” according to Variety. Then, in August 2017, a widely distributed anonymous email accused Belove of “sexual harassment, assault, and abuse by former employees and volunteers.” Though he denied the allegations, calling them “demonstrable lies and half-truths,” Belove resigned from Cinefamily days after the email was sent.

One of the few friends who continued to support Belove was a young film editor named Alex Lee Moyer, who had an idea for a documentary. The film would be about a group of driftless young men who gather on 4chan and Twitter to vent their frustration with their lack of romantic and professional prospects. Belove was drawn to the subject matter. He felt that these young men had been swept up in an online moral panic (this one over “incels”) and that a vérité documentary about their lives would make clear how overblown it had all been. He decided to help Moyer with the film, TFW NO GF (imageboard shorthand for “that feeling when no girlfriend.”) Right-wing politics hovered at the edges of the production; 3D-printed guns advocate Cody Wilson was an early financial supporter. But the documentary itself is affectless, refraining from any judgment of its subjects.

In March 2020, as Belove and Moyer were preparing to screen the film at the South by Southwest festival, they attended a live taping in Los Angeles of Other Life, a podcast about the niche ideologies that thrive online. The guest was Curtis Yarvin, a prolific blogger and software developer who first achieved notice under the pseudonym “Mencius Moldbug.” Writing as Moldbug from 2007 to 2014, Yarvin became synonymous with “neoreaction,” an abstruse political philosophy that prefers rational authoritarianism to democracy. To the extent that Yarvin is held to be dangerous rather than offensive or kooky, it is because of the sense that he represents an unexpressed current of antidemocratic belief in Silicon Valley. But when Belove listened to Yarvin speak, all he heard was a particularly intelligent bong-hit philosopher.

“Scared artists never win. And that’s why everything sucks right now. Everyone’s scared.”

The next day, Yarvin took Belove out to lunch in the upscale enclave of Los Feliz, and they ended up talking for 13 hours. Yarvin told Belove, presciently, that TFW NO GF would never screen at SXSW because of something called the novel coronavirus. But the men agreed that the film represented something serious: a model for transcending the culture war through ironic detachment. In 2020, this posture itself felt transgressive and cool.

“Art is more interesting than politics, and it’s impossible to create good art when you’re always looking over your shoulder,” Belove said. “You need a certain freedom from concern to create — scared artists never win. And that’s why everything sucks right now. Everyone’s scared.”

One drink turned into many. Belove told Yarvin he wanted to create something like the famous tech incubator Y Combinator, but for edgy, independent film. It would be completely outside the risk-averse, monocultural Hollywood system. And Yarvin knew VCs — one in particular.

Curtis Yarvin’s relationship with Peter Thiel is both well documented and incompletely understood. On the one hand, Yarvin is close enough with Thiel to have watched the 2016 election at the venture capitalist’s home and to have taken the billionaire’s investment capital for his startup, Tlon. (He also has emailed about politics with Thiel since at least 2013.) On the other hand, Thiel has invested in a variety of quixotic ventures, including 3D-printed meat and a floating island for libertarians. It can be a mug’s game to try to disentangle Thiel’s economic interests from his political commitments from his flights of intellectual fancy from the pet projects of his friends. Still, to the degree Thiel embodies Silicon Valley’s contrarianism, cultural insecurity, and nose for a new market, a “postwoke” film company seemed like a natural fit.

Thiel’s investments in politics have been high profile and consequential, but his ventures in culture and media — beyond funding the 2013 lawsuit that destroyed Gawker — have been scattershot. In 2018, BuzzFeed News revealed that Thiel had considered creating a conservative news network; nothing came of it. He funded the conservative political journal American Affairs, a contrarian science quarterly, and, according to a recent biography, the “heterodox” website Quillette. The Thiel Foundation subsidiary Imitatio, dedicated to the thought of the French philosopher René Girard, once purchased a table at a benefit put on by n+1, a leftist literary magazine.

It’s unclear exactly how much money Thiel Capital invested in Play Nice Ltd., which Belove registered in California in September 2020. (According to Belove, there are multiple investors, including others from the tech industry.) But at times, Thiel’s employees have been closely involved in Belove’s activities. In July 2021, Belove screened films and partied at the Cannes Film Festival with Jimmy Kaltreider, the executive director of the Thiel Foundation. In texts, Belove referred to members of Thiel Capital as his “traveling companions” and mentioned getting “approval” for expenses from Kaltreider.

By this point, Belove had cycled through several ideas for Play Nice. It could be a seed fund, or a production company, or maybe even a streaming service. Still, he was at heart a film programmer, and he loved the idea of a festival. In LA, Belove’s name was toxic. But he knew New York had a thriving young cultural scene, one nostalgic for an authentic city it never knew but half-remembered through the risk-taking films of the late ’80s and ’90s. Partially inspired by the notorious, defunct New York Underground Film Festival, Belove reached out in April 2021 to Ed Halter, its former director. “I got funding to support a new york underground film fest bringing together the new dirtbag film scene,” Belove wrote in an email. “I want to help expand it. We want to be all over town, pop-ups, secret screenings, no website, text invites like rave [...] real underground.”

Belove didn’t want to run the festival, in part because he knew his name would be a distraction. So who could help him find and mentor the young artists he wanted to attract? Belove had been collaborating on Play Nice with Lucas Leyva, the founder of a well-regarded Miami film collective called the Borscht Corporation. And Leyva said that he knew an extraordinary person who was just right for the job of creative director.

Trevor Bazile knew what the culture saw when it looked at him: a “royal flush of identities,” as one of his friends put it. Bazile was Black, he was queer, he didn’t have money, and he was the child of a Haitian immigrant. He was also, according to nearly everyone who encountered him, some kind of genius.

In 2017, Bazile turned up at Borscht to volunteer and never really left. Started in 2005 by Leyva, Borscht had a well-earned reputation for developing the talents of untrained, often first-generation American filmmakers. Oscar-winning director Barry Jenkins made a short film for Borscht, and he has said that Moonlight “would not exist” without the collective. As Borscht built its name, it drew investment from major institutional supporters of the arts, including the Knight Foundation, Time Warner, and the Andy Warhol Foundation.

By the time Bazile arrived, Borscht was already an established draw for eccentric young artists. Inspired by the idea of an authentic culture in a city known for its superficial glitz, Borscht fellows were a mix of posh kids with prestigious arts training and local kids from working-class families. (The program was administered by Dylan Redford, Robert’s grandson.) It was an exciting, combustible combination. Bazile stood out immediately.

“His brain was glow-in-the-dark, special,” Leyva said. “He thought differently from anyone else.”

Bazile made formally inventive, jazz-inflected short films, but also sculptures and installations. He would sleep in the Borscht space, located in an old mall in downtown Miami, and it became a second home. He started to lead a group of fellows who gave themselves the name “Bisque”; he pronounced with 22-year-old cockiness to older filmmakers that “we’re young, and I think we’re more talented.”

“His brain was glow-in-the-dark, special.”

The performance and consumption of Black identity was one of Bazile’s main themes. He told friends of his interest in the work of Jeremy O. Harris, the Black playwright, whose celebrated Slave Play is about contemporary interracial couples who do antebellum plantation roleplay to revive their flagging sex lives. In 2019, Bazile published a film interpretation of Charles Mingus’s spoken-word composition “The Clown.” The Mingus track is about a clown who realizes that the only thing that makes his audience laugh is inflicting physical pain on himself. In the film, Bazile’s frequent collaborator Nile Harris plays the clown. Harris, who is Black, performs increasingly degrading stunts in front of a stone-faced, largely white crowd. Finally, Harris ties a noose around his neck and attempts to hang himself. During his fall, the rope snaps, and he slaps the floor and screams for help. The audience finally laughs.

Bazile had a provocative streak that bordered on a compulsion to shock. In August 2019, with Borscht money, he designed a MAGA-red cap with the Migos lyric “you niggas in trouble” written across the front. Then he posted a collage of other fellows wearing the hat — some Black, some not — to Instagram. The hat prompted outrage, and people — some Black, some not — accused Bazile on social media of being a “resident negro” and a “minstrel,” and Borscht of being racist by association. But Leyva defended his talented protégé.

In January 2020, a woman published a blog post (since removed) accusing Lucas Leyva of sexual assault. Leyva insists that the encounter was consensual, as does a second woman who participated; he filed a defamation suit, which is ongoing. Before he resigned as president, Leyva lobbied the Borscht board to replace him with Bazile. They turned Leyva’s request down. (It ended up not mattering. The Knight Foundation discontinued its support, and today Borscht is essentially defunct.)

Bazile’s professional ambitions had been denied. With Borscht crumbling, he had lost the space and the money to make art. Then the coronavirus closed down the city. Friends who came from money retreated to the safety of their family homes. Bazile lashed out on social media against people he thought were trying to take down Borscht. He spent more of his time on Instagram, making a name for himself in the obscure reaches of Politigram and Theorygram, loose but committed communities of posters who make densely ironic memes about topics like anarcho-capitalism and French philosopher Gilles Deleuze.

During the George Floyd protests, as Instagram filled up with black squares and calls for donations to racial justice causes of varying seriousness, Bazile told friends that he was overcome by cynicism. With his “royal flush” of identities, cancel culture should work for him, he said to a friend. But here he was without prospects, all because of Borscht being canceled. Meanwhile, wealthy people he knew, people who didn’t care about him or Black people in general, were making symbolic gestures — chasing clout — on social media. Bazile told friends that he was drawn to Afropessimism, a bleak philosophy of race arguing that anti-Black violence is so fundamental to the nature of Western society that the only way to end it would be to end the world as we know it.

Cancellation was a form of currency, maybe the only one he had.

In a December 2020 appearance on the cult film podcast The Ion Pack, Bazile said that around this time, he’d dropped acid and had a “mental breakdown.” But the trip led to a moment of clarity: The culture that had robbed him had its own rules, which he could use to his advantage. “If I act like how people on these apps are acting, who are trying to chase social capital by canceling people, I need to participate in this market,” he said on the podcast. Cancellation was a form of currency, maybe the only one he had. “That’s when I started shitposting — posting the most terrible things I could. I haven’t stopped since then.”

It’s hard to explain what Bazile did on Instagram starting in mid-2020. First of all, he kept getting banned, so only one of his accounts, @all_triggers _no _warnings, is still accessible. Second, he posted things that are so offensive they are tricky to describe. He posted at such a blistering pace and in such contradictory ways that to fasten it down with adjectives feels beside the point. Bazile posted pro-Trump memes and anti-Trump memes, images of Jeffrey Epstein and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in blackface, memes mocking anti-fat discourse, a photograph of a Hegel T-shirt, hundreds of bizarre and abject clips he found on TikTok, a drawing of a Black man performing fellatio on a white penis at the summit of a milk crate challenge. He took so many political stances that he seemed to be mocking the idea of having a political stance at all. He gained access to a massively ironic Instagram collective called the Incellectuals, then got booted for being too offensive.

In a cult scene, Bazile became a cult figure. “Ironic Blackness needs to take up digital space,” he said in the Ion Pack interview. Leftists were taking back online irony from “alt-right motherfuckers,” he said, and centrists just couldn’t deal. One of his gimmicks was to respond to offended white commenters with a link to his Cash App, as if to say, If you want me to read your opinion, you have to pay me.

These payments kept Bazile afloat for a while, but eventually he had to take a job at an upscale ice cream parlor. He didn’t have a car; he begged for rides; he crashed on couches. When Leyva asked him whether he wanted to be the creative director of the NPCC, he said yes.

“What does it matter if it’s George Soros or Peter Thiel who is giving it to me?”

Some of Bazile’s friends were unsettled that he was going to work for a festival that was funded by Thiel’s money and created by a disgraced man plotting a second act. In long arguments over Instagram DMs that summer, Bazile said to friends that the NPCC was a chance to make work that conventional patrons would never support.

“There was a constant fight between what he wanted to say and what a liberal institution would want him to say or make work about,” Pedro Bello, a friend of his, told me.

He also made it clear that his relationships with Belove and Thiel were transactional. He knew he was a convenient face for the festival, but he knew NPCC was an opportunity. That was the exchange: Use and be used alike.

“He needed backers to do what he wanted to do,” said a friend of Bazile’s, who asked that I identify him by his Instagram handle, @gaypanique2. “He saw it as a wager. The wager he was making was, ‘I’m going to deal with these unsavory people.’ It was very practical. He was not hiding anything. ‘I’m poor, I need money, I need money to do art. What does it matter if it’s George Soros or Peter Thiel who is giving it to me? We’re going to celebrate and laugh in the face of destruction.’”

Bazile arrived in New York in July 2021, rented an apartment in Brooklyn, and went about trying to organize a film festival. He had to contend with Hadrian Belove’s reputation. Cinefamily’s implosion had left a crater in the independent film scene in LA, and now Belove had shown up on the East Coast, trailed by rumors that he had financial support from Thiel. Filmmaker after filmmaker turned Bazile and his two young co-organizers down, unwilling or afraid to participate in what had become known unofficially as the “anti-woke film festival.”

But Bazile had cachet among a new clique of Instagram-obsessed Manhattan scenesters. At a July party at Russian Samovar thrown by The Ion Pack and cohosted by influencer Caroline Calloway, Leyva watched, amused, as a crowd of people formed around his old fellow, hoping to meet Trevor “Memes” Bazile. (A Grub Street party report described the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd as “hordes of very white, very young, very online people.”) It was the exact scene Belove had hoped to leverage.

“This clout shit crazy,” Bazile told Leyva afterward with a wink.

Bazile and his co-organizers slowly put together a lineup of 23 films. It included screenings of a debut by a high school teacher, an Austrian movie about an android, two older works involving literary men in various stages of post-cancellation cultural limbo, and the debut of a short film by Kids director Larry Clark. Alex Lee Moyer screened a cut of her follow-up to TFW NO GF, a strenuously amoral, vérité documentary about Alex Jones.

Up until the last minute, the NPCC suffered cancellations — real ones. Clark fell out for medical reasons, then The Ion Pack hosts, who were set to interview the filmmaker, withdrew. Then noise band Wolf Eyes dropped out. The Ace Hotel was originally supposed to host Bazile’s big party but backed out after staffers were alarmed by offensive jokes on the NPCC’s Twitter account, which Bazile ran.

“The central themes of our festival are around transgression and deplatformed voices,” Bazile wrote in an email to an Ace spokesperson. “In contemporary liberal art spaces, especially those that exist online, whenever an artist engages themes of transgression or subversion they are assumed to be right wing, or white supremacist, regardless of the intent or content of their work.”

Then, only a week before the festival was set to begin, a Brooklyn synagogue informed the organizers that it would no longer host Red Scare and John Waters because anonymous callers had claimed the festival was antisemitic.

The best-known filmmaker to attend the NPCC and show their work was Caveh Zahedi, whose documentaries the New York Times called in a 2019 profile “abject, self-defeating, ethically questionable, and maddeningly original.” Friends and colleagues at the New School tried to talk him out of doing the festival because of the Thiel money, a request he found hypocritical given the compromised nature of film funding in general.

“Look at what we’re doing with your money, you dick.”

“A lot of the grants people get come from horrible abuses that generate tons of profit that make philanthropy possible in the first place,” he told me. One of the director’s most loved films, The Sheik and I, was originally commissioned for the 2011 Sharjah Biennial on the theme of “art as a subversive act.” The film Zahedi ended up making so ruthlessly satirized the United Arab Emirates that it was banned, and the director himself was threatened with arrest. In Zahedi’s world, it doesn’t make sense for an artist to reject bad money, because the system that gives the money value is itself bad; rather, the artist should take bad money and use it to make a statement.

But what kind of statement did Bazile want to make? A dedicated observer of the strange and shifting politics of the internet might squint and see in his NPCC something like a coming-out party for the “Post Left,” a strange and shifting term. Derided by journalist Carl Beijer as “an internet clique waiting on a check,” the “Post Left” sometimes refers to a group of online media figures who reject the American left as insufficiently radical and align themselves with Trumpian positions on identity politics.

More importantly, it describes a chaotic internet subculture that is closely associated with the depressive outlook of Gen Z — the milieu in which Bazile had become a minor star. Better thought of as an attitude than a coherent politics, this “Post Left” associates identity politics with self-righteous millennials and confused boomers. So too does it reject electoral politics, which it sees as fatally compromised by capitalism and preposterously insufficient to the task of addressing the climate crisis. Gleefully ironic, this sensibility can verge on nihilism. But it also takes the sympathetic position that the most appropriate response to the end of the world might be to laugh and play.

Especially if Peter Thiel is paying.

Several months after the festival, Nile Harris, Bazile’s collaborator, posted to Instagram a picture of the pair on the Eldridge Street roof, standing inside a deflated blow-up castle in front of a painted white brick wall. In the photograph, they both stare into the camera. “Peter Thiel bought me a house,” the caption reads. “But this house is not a home.”

“It felt like, look at what we can do with his money,” one attendee said. “Look at what we’re doing with your money, you dick.”

Generations of artists have defined themselves by rebelling against the values of the bourgeoisie. But a subculture based on transgressing bourgeois norms in 2021 faces a trap: It can look indistinguishable from Trumpism. The distinction between shocking liberals as an aesthetic goal and a political one starts to blur.

To wit, Vice magazine gave the world an original cultural sensibility, but it also gave the world Gavin McInnes, the founder of the Proud Boys. While working on her documentary about Alex Jones, Moyer attended the Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally; that day, she posted to Instagram a photograph in the hotel room of pro-Trump indie musician Ariel Pink, who did the soundtrack for TFW NO GF and had attended the rally in support of the former President. The attempt to re-create a scuzzy hipster nihilism — with the cash of the Trumpist right’s most notorious financier — feels to some like the farce arriving before the tragedy has even ended. That’s why Ed Halter, the old New York Underground Film Festival organizer, never responded to Hadrian Belove’s email.

“I have a Gen X embarrassment about this myself,” said Halter, who is now a critic in residence at Bard College. “I understand why they reached out to me. For that very reason I did not want to be any part of that. I felt the transgressiveness of the ’90s was anti-political, whereas now it’s being harnessed to a cynical right-wing politics. And I feel old enough now to see the trick.”

What makes the new transgressive culture more complicated is it sees the trick as well — and folds it into the joke. Indeed, “Thiel as fascist paymaster” is now such a media trope that it has become a kind of meme in the Post Left, with associated microcelebrities joking about "needing Thiel money" or being Venmo’d by him. “Thielbucks,” as Post Left internet communities sometimes call them, are, in this sense, less important as a source of income than as a shock tactic; claiming them, ironically or otherwise, confers its own bizarro credibility.

“You’re telling me Black people are getting killed, and it’s a psyop? What do you actually believe?”

One performer at the NPCC was the DJ Aloiso Wilmoth, though he’s also known for an Instagram account, @moma.ps5, where he posts Marxist cultural criticism. Wilmoth and Trevor Bazile had known each other for years through the platform, where they expressed their frustrations with social justice in the digital age. But Wilmoth, who is Black, became disillusioned with the Post Left, which he felt had an unacceptably detached response to the racial justice protests of 2020. “During the uprising, they were calling it a ‘psyop,’” he said. “You’re telling me Black people are getting killed, and it’s a psyop? What do you actually believe?”

When Wilmoth started to push back against these kinds of claims, he was astonished by the intensity of the response. “They would get so angry,” he said. The so-called Post Left, it seemed, only appreciated a Black ironist of Black identity politics under certain conditions. “They are more obsessed with aesthetics as opposed to tangible material liberation.”

Among the people reading poetry at an NPCC event on Oct. 23 was neoreactionary writer Curtis Yarvin, who looms large in the anti-fascist imagination. That morning, the @NYCAntifa Twitter account posted about the reading, publishing the address of the “shitty edgelord film festival” where “veiled fascist” Yarvin would perform. Wilmoth, who was unaware of Thiel's involvement until after the festival, looked around the room and felt a kind of cognitive dissonance, unsure whether it was the “birth of a new scene” or the motley pieces of Bazile’s internet failing to cohere.

Meanwhile, Bazile himself was having trouble keeping it all together. According to Wilmoth, Bazile texted him that he was being “worked like a slave.” Bazile told Gaypanique, who had traveled to New York for the festival, that he couldn’t get the ADHD medication he needed to focus; people who met him throughout the four days noticed that he seemed wired at times and withdrawn at others. One friend, who saw Bazile looking glum during a screening, asked him what was wrong. “Trevor problems,” he responded.

“I need you to rip it to shreds.”

In the days leading up to the NPCC festival, Bazile had confided in Gaypanique that he feared there was no organic reason for it to exist beyond Thiel’s money and Belove’s ego. So when Gaypanique saw Bazile on the last day of the festival, he congratulated him: He had pulled off something on his own terms. But Bazile scoffed. “I don’t think I have the capacity to do this anymore,” he said, cryptically, about the festival. “I need you to rip it to shreds.”

That night, a Philadelphia bartender named Victor Kane, who owns a popular meme account on Instagram called @chethanxfinsta, arrived in Brooklyn to find Bazile distraught. Early the next morning, Kane posted an Instagram story. On top of a rainbow background, he wrote that he had spent the night at Bazile’s apartment:

“When I got there he looked like he had way too much to drink [...] We went out and grabbed a couple drinks and returned to the Airbnb to chill and fall asleepv. I told him that I was worried bc he was covered in sweat and was wheezing [...] he told me he was just tired and fat and the wheezing was normal. Still I crashed on the floor next to him to make sure he was okay. Unfortunately I fell asleep for 30 mins and when I woke up he was no longer breathing. I immediately called 911 and they spent over an hour trying to bring him back however they were not successful. It is with the heaviest heart I have to inform everyone that Trevor passed away at 307am last night and is no longer with us.”

Then he posted a picture of Bazile, underneath a rippling digital banner. It read, “Rest in Power.”

When Bazile’s friends first saw the posts, many of them assumed it was a joke. Even in the irony-saturated world he inhabited, who would announce a death that way? But it was true. Bazile was dead. He was only 25. According to Trenny Hardy, Bazile’s mother, the New York City death certificate lists the cause as “pending further study.”

On Oct. 29, the NPCC Instagram made an announcement.

“He cared deeply about art, and the need for a kind of creative freedom and openness that could be wildly transgressive,” it read. “When he pitched the name of NPC fest, he said it was because that’s what culture was turning everyone into—people without independent thought—and that by naming the fest NPC, we could reclaim this concept and cast a sort of spell to free everyone from it.”

“NPC” is an initialism from computer role-playing games, short for “nonplayer character.” It refers to a digital avatar that is controlled by the computer rather than by the player, a digital life running on a little loop. That’s the way Trevor Bazile saw the state of American culture in the 2020s: repetitive, preprogrammed, dull. But blaming liberal politics for that repetition ignores deeper cultural tracks laid down over the past two decades by a handful of companies in Silicon Valley, owned and operated by a tiny group of billionaires. Any protest of that system from within can be copied, commodified, and turned into its own kind of script.

Since Trevor Bazile’s death, there’s been sniping on Twitter about higher-profile, white posters stealing his memes, denaturing his ideas, and taking credit. And so much of his work has been scrubbed from the internet by Instagram that it’s hard to say what, exactly, Bazile left behind. For an artist obsessed with taking up new kinds of space, he has in some ways already disappeared. Had Bazile lived, friends think he might have redefined indie film in New York or turned into a Virgil Abloh figure. In five years, they say, we’ll catch up to what he was thinking.

“He was not ready yet to be seen,” said Pedro Bello, the friend from Miami. “He was still trapped pleasing people to reach his goals. His sentence is not complete.”

In the end, the attempt to re-create in miniature the druggy, anything-goes downtown Manhattan of the 1990s ended with a brilliant young person dying. You could call it ironic, if you wanted to. A deeper irony is that beneath the NPCC’s rhetoric of transgression lay a perfectly neat series of exchanges: money for cultural influence, money for identity, identity for clout, and so on. Indeed, Peter Thiel’s real influence over the “postwoke,” or the “Post Left,” or whatever this sensibility comes to be called, might be thought of in a different way. The subculture has the same logic as the tech oligarchy that Thiel embodies. It follows the same rules — imitate, iterate, transact.

At the screening of the Alex Jones documentary, the audience had to sign nondisclosure agreements: legal documents ensuring corporate secrecy, at the transgressive film festival. It was all very Silicon Valley. ●