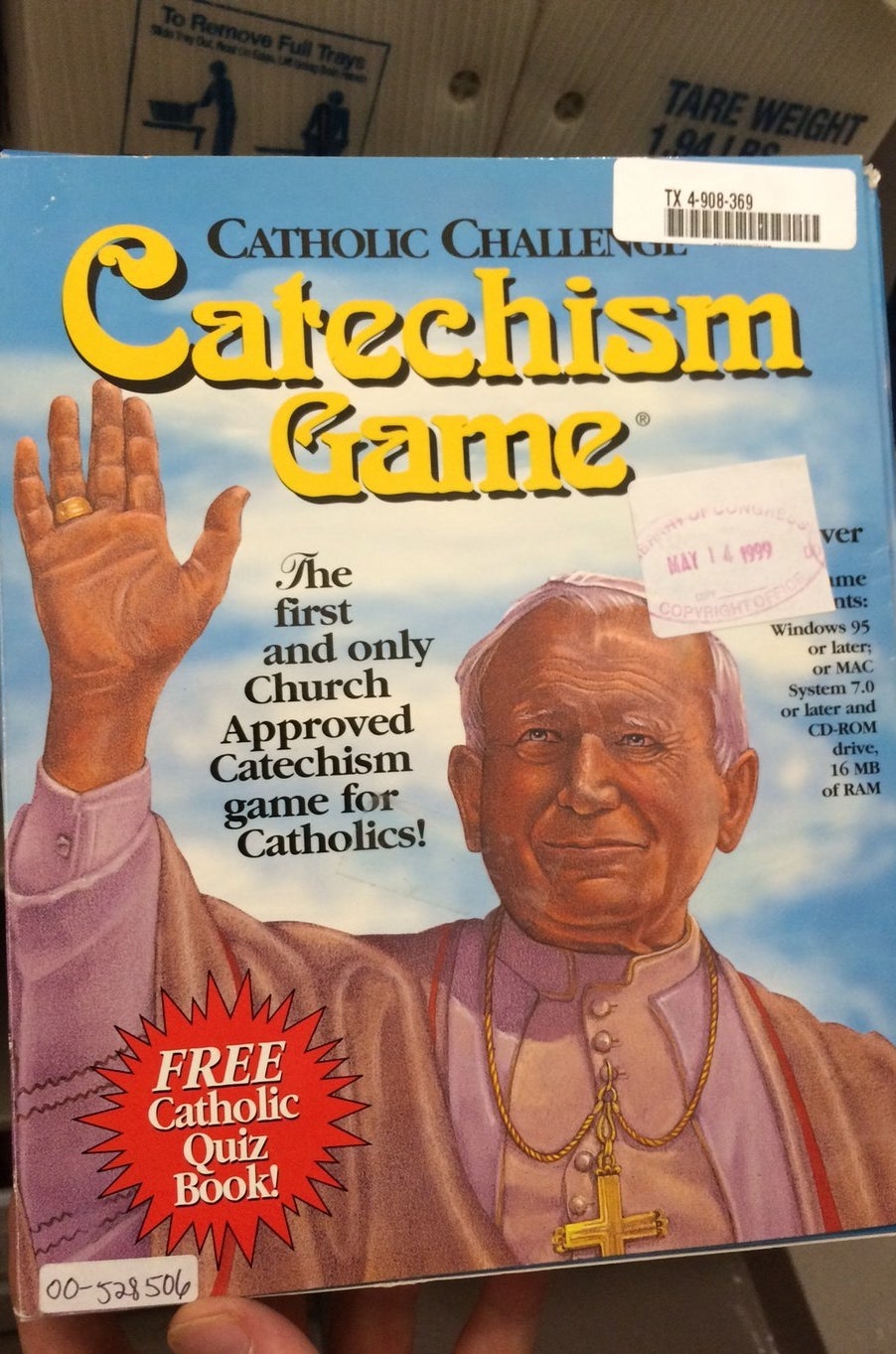

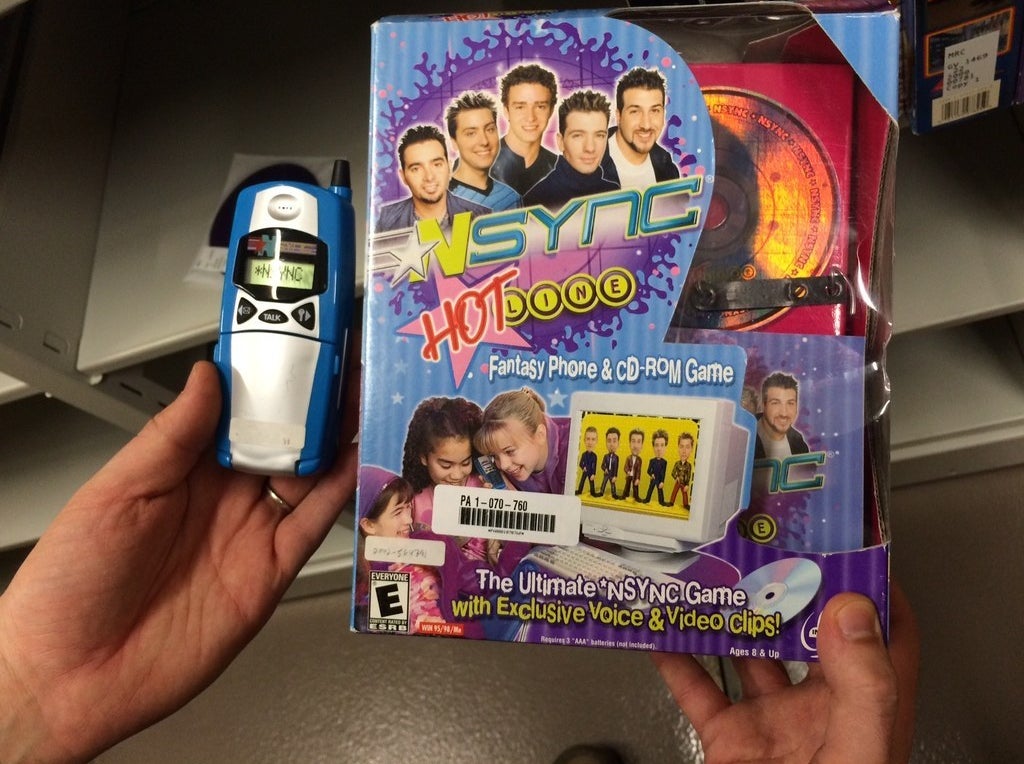

Dave Gibson can tell you about some of the weirdest video games ever released: A 1995 Mac game narrated by David Sedaris, for example, or The Catechism Game, which touts itself as "The first and only Church Approved Catechism Game for Catholics!", or better yet, 'N Sync Hotline, a 2001 PC game that came bundled with a cordless phone capable of delivering special bedtime messages from Justin Timberlake and Joey Fatone.

As a moving image technician at the Library of Congress' National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Gibson — along with a few colleagues — sorts through all of the games coming in for copyright, parses private donations, and can wax proudly about the rare jewels of the Library's game collection.

In other words, if there's a video game Librarian of Congress, it's probably Dave Gibson. He's the expert. And yet, he only spends a quarter of his time working with games.

No, the work of game copyrighting and archiving at our country's signal institution for cultural preservation is not done by a dedicated full-time staff. Instead, it's the passion project of a handful of archivists who want to be the new standard-bearers in the preservation of video games. Indeed, the state of video game collection at the Library is something of an expression of the liminal state of video games in American popular culture writ large. The Library recognizes the cultural importance of video games, but only devotes four people part-time to their archiving; Game companies insist that their products are the medium of the future, but don't trust archives with their source code; Collectors sell their troves on Craigslist and eBay rather than considering donation.

Even to get to this point, though, has been a journey in and of itself.

In 2007, the Library of Congress moved its gargantuan collection of audio-visual material from Capitol Hill to a vault underneath a hillside in Culpepper, Virginia, alongside some of the world's most precious A/V artifacts. The 6.3 million items transferred to the brand-new Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation included the original negatives of Casablanca, the first-ever 45-rpm record, and the original broadcast reel of NBC moving from black and white to color television.

Among the treasures — and the comprehensive collection of C-Span footage — was a unique tranche: 3,000 pieces of software, or the Library's entire archive of computer games. They're kept in large manila folders on shelf after shelf deep within Packard.

"It is part of our mandate to preserve, collect, and make accessible the riches of American creativity," said Mike Mashon, the Head of the Moving Image section of Packard, who personally lobbied to make Packard responsible for games. "And video games are a vital part of that."

That original collection was far from comprehensive. Mostly PC games, the titles were generally archived either because they had some perceived educational value (Reader Rabbit), because they were controversial enough to enter the cultural conversation (Grand Theft Auto), or because they were ubiquitous (Myst, The Sims).

Today, that archive has doubled to more than 6,000 titles. This patchwork — the original endowment, plus thousands of games received and sorted for copyright, plus private donations — is the domain of Gibson and three colleagues, Trevor Owens, Brian Taves, and David March.

Gibson, 37, whose mop of straw-colored hair, baby face, and contagious excitement give him the aspect of a recovering teenager, grew up in North Carolina playing games. He studied moving image archiving at UCLA, and started working for the Library of Congress in 2006. When the Moving Image Section acquired the Library's games, he knew it was a rare opportunity.

"It's fallen to us to deal with games," Gibson said. "We want to collect for the sake of archiving our nation's video gaming heritage."

He and the team face enormous logistical, technical, and bureaucratic challenges. Today, there is no established standard for the copyrighting, or cataloguing, of video games.

Prior to the early 1990s, the Library simply required a written description of the game. "We probably have a written description of Mario," Gibson said, "somewhere in a warehouse next to the Ark of the Covenant." From the early 1990s to 2007, the Library upped its requirements for copyright to a description, 50 pages of source code, and a half-hour video of gameplay. It was an improvement, but hardly up to the standards of movies: The Library has its own several-volume tome dedicated to the standard cataloguing and copyright of moving images. After the move to Packard, the Library started recommending, but not requiring, an actual copy of the game. Gibson estimates that Packard now receives about a quarter of all new releases.

But just keeping up with newly released material is a daunting task. Every week, Gibson and his colleagues have to sort through several massive tubs brimming with material to be copyrighted. A game might come in six or seven different editions, each for a different platform. Having a standard system of archiving and copyrighting — something currently being discussed by the Library's Recommended Format Specification Group — would make the job significantly easier. It would also clarify the work of the other major game archives, at Stanford, the University of Texas, and the Strong Museum in Rochester, New York.

"I suspect that when motion pictures first started arriving here in the 1890s, these same discussions were taking place," said Mashon. Indeed, the Packard collection includes paper prints of early films — long strips of photographic paper containing every frame in a movie — that were the first copyright standard for the medium. Movies can be recreated from these prints; Gibson sees the source code of games as a similar, genetic, reference.

More pressingly, the Moving Image Collection currently has no good way of dealing with digitally distributed media, and not just video games. The Library's processes are, by the standards of 21st century media consumption, antiquated. Netflix has to print special VHS copies of their streaming hits like Orange Is the New Black and House of Cards for copyright consideration. As games move toward exclusively digital formats, the Library has to standardize digital specifications for fiber optic copyright submission, and then it needs the major game publishers to comply.

The Library has strong relationships with big film studios, who come to Packard for prints when they want to publish new editions. Many game publishers, though, see the archivists' desire for comprehensiveness as a threat. "Most game companies," Gibson wrote in 2012, "view the source codes as trade secrets not to be distributed." That, according to Gibson, is a mistake, especially since the Library keeps all material under lock and key. "Archives are trying to save and legitimize the things they're making," he said.

And Gibson's work has already gone well beyond cataloguing into real discovery and preservation. Earlier this year, Gibson found a DVD-R loaded with a file directory containing comprehensive assets for a Duke Nukem game developed for the PlayStation Portable that had never been released. Working with a Packard software developer, Gibson was able to access the proprietary asset formats and see glimpses of a game thought lost to time, something that's especially important as technology accelerates the cycles of obsolescence for consoles and software.

"The discovery of that which has been lost or previously unattainable is one of the driving forces behind the archival profession and one of the passions the profession shares with the gaming community," Gibson wrote in a blog post in August.

And that's the promise of a well-staffed game archive — discovering and preserving aspects of culture beyond the interest or reach of the people who make them, for the people who are fascinated by them. Which raises the question: When will the Packard campus have such a staff?

"If I could do it today I would," said Mashon, the Moving Image head. "But video games are terra incognito and Dave is helping us blaze that path. In a perfect world, within a few years I'd like to say we'd have at least one person who is devoted to games. We could use it."

In the meantime, it will be up to Gibson and his fellow part-timers to establish the practices and standards by which the archivists of the future will collect our newest cultural medium: "Our duty as custodians of American creativity is to archive this stuff."