There have been two reactions to Starseed Pilgrim, the obscure and possibly brilliant indie game released last week on Steam. The first is rapturous praise, and it has come from some of the most respected minds in gaming.

No less a luminary than Jonathan Blow, The Atlantic-profiled swami behind Braid, has called the game one of his favorites of all time. "Advice for playing Starseed Pilgrim: As long as you still have questions, continue."

And says Bennett Foddy, the creator of the frustration masterpieces QWOP and GIRP: "If I could only recommend one more game for the rest of my life, it would be Starseed Pilgrim."

The other, more common reaction to the game is a kind of genial, but total, confusion. It's best demonstrated by the editors at Giant Bomb in their video "Quick Look," which is nearly profound if you close your eyes and listen to the mix of Seuss and Beckett into which their conversation descends: "It's turned the blocks into not-blocks!"; "I have no idea why that would be useful at this current juncture"; "This blue one. I'm not really sure."

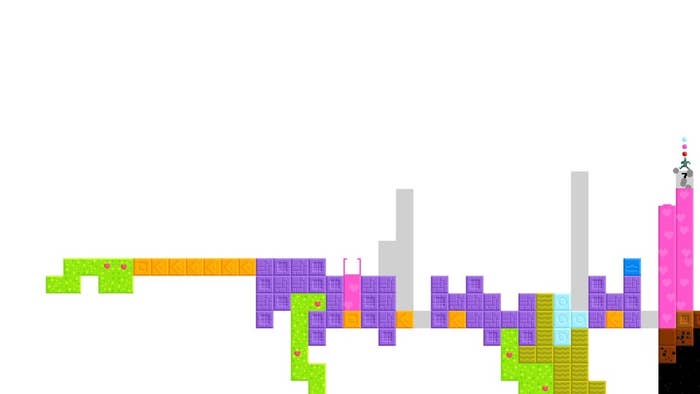

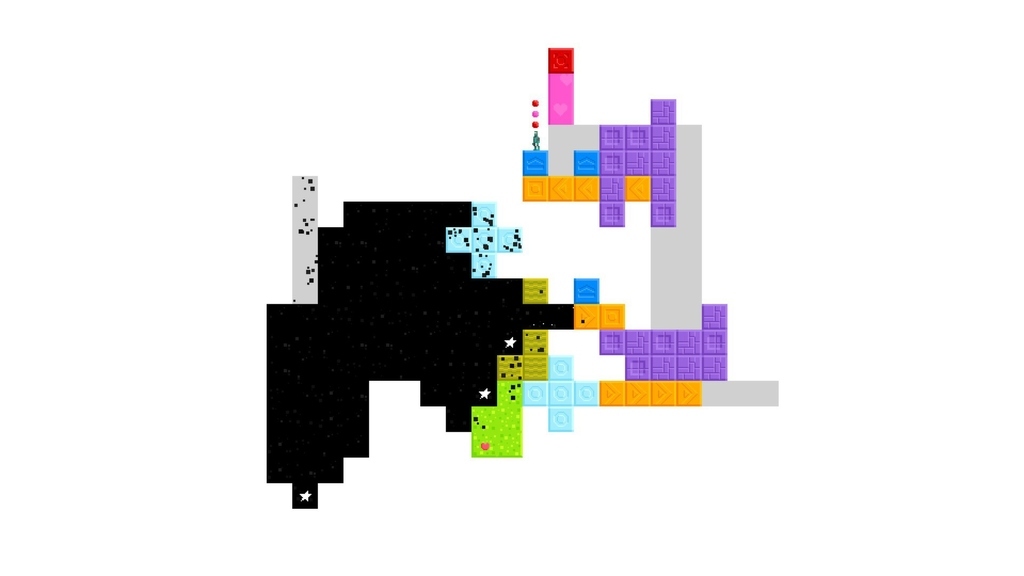

So what, exactly, is Starseed Pilgrim? Well, to the extent that the game has a premise, it is that you play as a tiny gardener, who plants a limited but renewable stock of seeds into a series of floating blocks. These seeds in turn produce more blocks of different kinds, and the early, baffling portion of the game is spent determining which blocks do what. All the while, your garden decays, and so you are required to keep planting and moving.

Or not — the game doesn't really tell you, and that, as many have noted, is sort of the point. While Starseed Pilgrim has a definite and consistent set of rules, it does no more than gesture at a few of them, leaving their discovery up to the player. It's rather like being handed a particularly difficult record by a friend. It's not hard, really, but it does require patience; you have to learn how to listen to it. As you can probably tell, we are very far from the blasty, overwrought worlds of Master Chief and Nathan Drake, and firmly in the economical and overtly symbolic territory of the indie game.

The reason Foddy and Blow love the game so much is that it so totally reflects the values of the indie game scene as they see it: Mechanics above narrative, obscurity above accessibility, procedural generation (a fancy way of saying random and on the fly) above prefabricated design. The point of a game like this is almost entirely in figuring out what kind of game it is and how to play it.

Your opinion of Starseed Pilgrim will likely depend on the role you want games to play in your life. If you see games as a distraction and an escape — pure entertainment — you will probably find this game to be a weird and slightly pretentious curiosity (and if we can eliminate bad cryptic prose from indie games forever, I will be a very happy man). If you want games to be slow processes of discovery — struggles — you will find this game extremely rewarding. Neither approach is right; people look for their art in different places. Some people find it in the cinema, some over their speakers, some on their Kindle, and an increasing number, to be sure, on Steam.