WORCESTER, Massachusetts — Standing outside Rumors nightclub in Worcester, Massachusetts, Cesar Diaz Alvarenga, a rapper from El Salvador who goes by Debil Estar, watched as the last patrons of the bar sprinted across the street through the cold rain. He’d just finished a show here for a few dozen people, mostly friends and family visiting from El Salvador.

A member of the rap group Pescozada who also happens to have a law degree, Debil Estar is a veteran of El Salvador’s hip-hop scene and a pioneer of Salvadoran conscious hip-hop, which emphasizes lyrics that are often critical of the government.

And that, he said, has become a problem. “Freedom of speech in Salvador is — well, it’s a new concept for our police,” said Debil Estar, 36, who lives in San Salvador and was touring the US this summer.

One of his first run-ins with the Salvadoran police came a decade ago, when cops began profiling potential gang members based on their clothes — including the baggy shorts, sneakers, and American sports jerseys that are ubiquitous in hip-hop circles.

Pescozada had begun making a name for themselves with politically minded lyrics and danceable beats, and the government had taken notice, he said.

For more on this story, watch Follow This on Netflix.

Following a show one night in El Salvador, the band was pulled over. “The police put their guns in our car windows” and forced the members out of the car, Debil Estar recalled. They began searching the car for drugs or guns but found nothing, he said. As a lawyer, “I try to do things legal,” he said, smiling.

Although nothing happened that night, the police have continued to harass the band and their fans, insisting that because of rap’s popularity with violent gangs like MS-13, anyone associated with it is potentially a dangerous criminal. More than once, he said, police have come to his shows.

It’s a common story among members of El Salvador’s hip-hop community, who’ve found themselves caught in the crossfire between a corrupt, violent police force and the street gangs that spread fear and death across the country.

Targeting rappers has helped law enforcement in the US and El Salvador combat gangs: According to US law enforcement officials, they’ve successfully used the lyrics in songs produced by members of MS-13 in building murder cases.

But it’s also come at a cost. “We have about 20 artists, hip-hop artists that [have been] disappeared. We don‘t know the reasons, we don’t know what happened with them, really,” Debil Estar said.

Debil Estar and other artists were careful not to outright accuse the government of murdering their colleagues, all of whom they said were known for socially progressive lyrics that often criticized the government.

But they made clear the disappearances have occurred at the same time that the police and the military have targeted people for wearing clothes associated with hip-hop culture. “That’s crazy, because the hip-hop is music. But ... a lot of police sometimes don’t understand when the person is an artist or a fan [of] the music.

Between the late 1970s and early 1990s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadoran refugees came to the United States, fleeing the war between guerrillas and the US-backed military-led government. Large communities of Salvadorans took hold in places like Los Angeles, Washington, DC, and New York.

As a result, an entire generation of Salvadoran young people came of age in the US as hip-hop was becoming the dominant pop culture force in the United States. Gangster rap replaced the heavy metal soundtrack for Salvadoran gang members in Los Angeles. In New York, the first Salvadoran hip-hop group, Reyes del Bajo Mundo, formed in 1992.

But in 1994, the Clinton administration began a series of mass deportations in response to pressure from Republicans to address the growing numbers of migrants coming to the country. Thousands of Salvadorans, many of whom had come to the United States as small children, were swept up in these deportations, and they took much of the culture they’d adopted home with them.

“Our structures, our malls and stuff, they’re all American influence. With the music we listen to on the radio, it’s all American influence,” said Raul "Loup Rouge" Hidalgo, a Salvadoran producer and DJ who was born in Queens, New York.

So it was natural for hip-hop to find a home in El Salvador.

But the newcomers also brought the gangs, most notably MS-13, which had been founded more than a decade earlier in Los Angeles. Freed from the constraints of the US legal system, the gangs flourished, perfecting their brand of terror on the civilian population as they battled a government for control of huge swaths of the country.

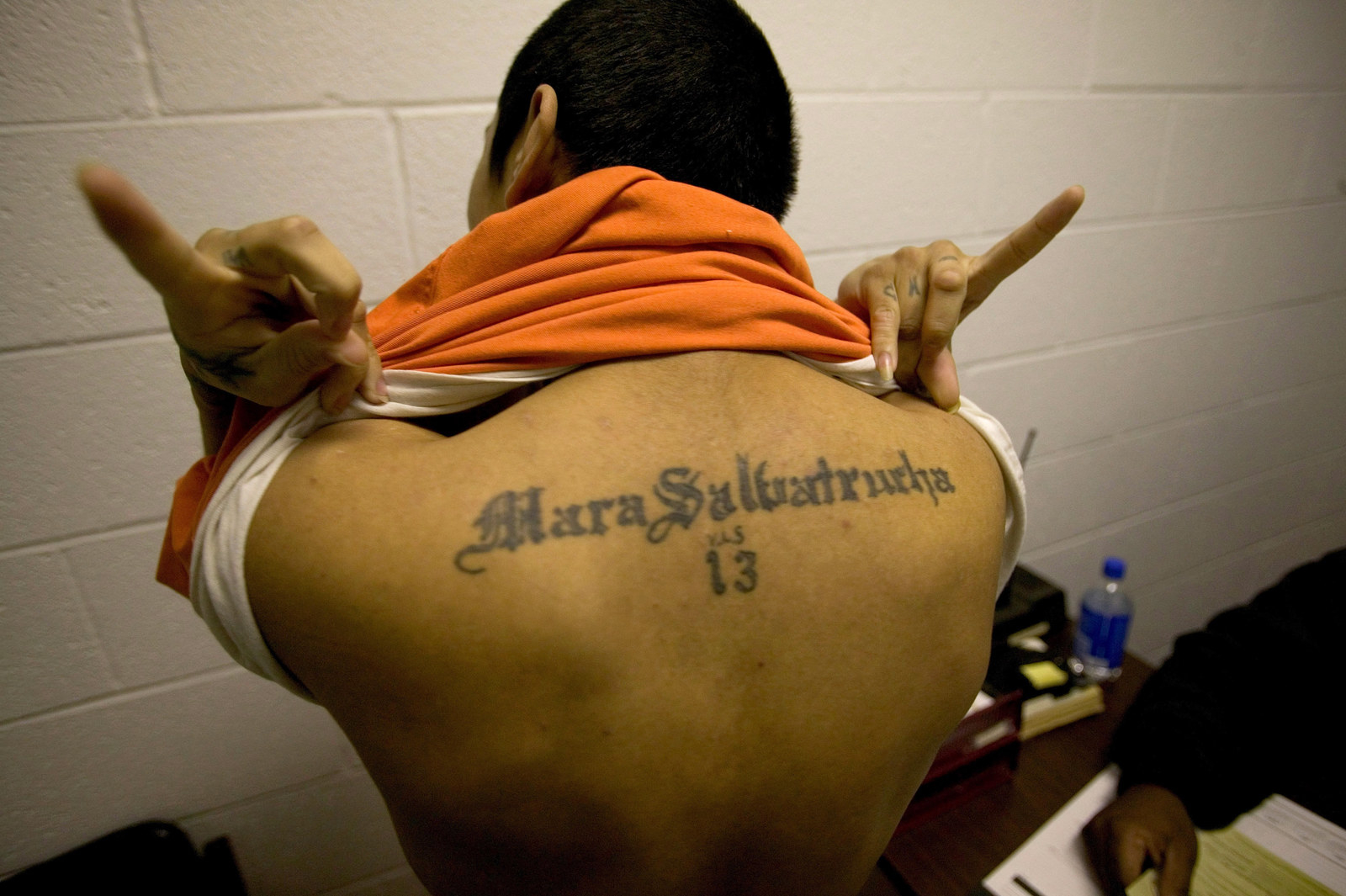

By the late 2000s, MS-13 rappers were beginning to produce their own records, extolling the violence and prowess of the gang. Studios catering to the gang members sprang up, and the rappers have since used YouTube, WhatsApp, and other social media platforms to share their songs, which include shoutouts to specific gang members and often explicit details of the crimes they’ve committed.

Although it took police in the United States and El Salvador time to catch up, these videos have become an increasingly useful tool in targeting gang members. In the US, for instance, law enforcement in Virginia has used them to directly connect alleged members to the gangs, and the videos have helped police build murder cases in the area.

In El Salvador, authorities have taken it further, using the gangs’ connections to hip-hop to justify what amounts to cultural profiling under measures like the 2010 legislation formally titled Law Banning Criminal Gangs, Bands, Groups, Associations and Organizations.

Having visible tattoos or wearing certain colors — or even baggy shorts and US sports jerseys — can run you afoul of the police. And authorities have taken an extremely broad interpretation of that authority, so much so that visitors to the country are routinely warned to be careful if they display tattoos or wear certain clothing in areas not frequented by tourists.

“It’s so, so easy to get stopped,” said Hidalgo. “You can be walking in a mall and they’ll just stop you and demand you take off your shirt.”

“If it’s baggy, you’re automatically seen as a gang member ... and the gangs have evolved. A lot of gang members don’t even have tattoos. They look like normal people,” Hidalgo said.

Sticking out can be potentially deadly for members of the hip-hop community. At least four high-profile members of the community have either disappeared or died in police custody since March 2016, when Emilio “Milo” Bolaños went missing. A popular breakdancer, Bolaños was well-known not just in El Salvador but in international B-boy circles. His disappearance, which remains unsolved, according to Hidalgo, was the “first in the scene that made people start taking notice of this stuff.”

In 2017, veteran Salvadoran MC Blaze One died in police custody after being arrested for possession of marijuana. Most recently, MC Bacteria, a 29-year-old rapper and activist from San Salvador, disappeared in January.

Nobody knows for sure what’s happened to the members of the hip-hop community. Being “disappeared” has been a particularly pernicious terror in the country since the late 1970s, when the government first began using it as a tactic in its war against insurgents.

Although traditionally not favored by MS-13 and other gangs — which have instead used killings to send public messages to others in the community — in recent years the tactic has become more common.

“Unfortunately, it is kind of the standard way. And not just within the hip-hop community, but the country as a whole,” said Hidalgo, who tears up whenever he talks about his friends, particularly Blaze One.

“He was a great friend of mine, and he’s not with us anymore. And it’s hard. Just listening to— to his music, you know, just to kind of hear his voice again. It’s sad.”