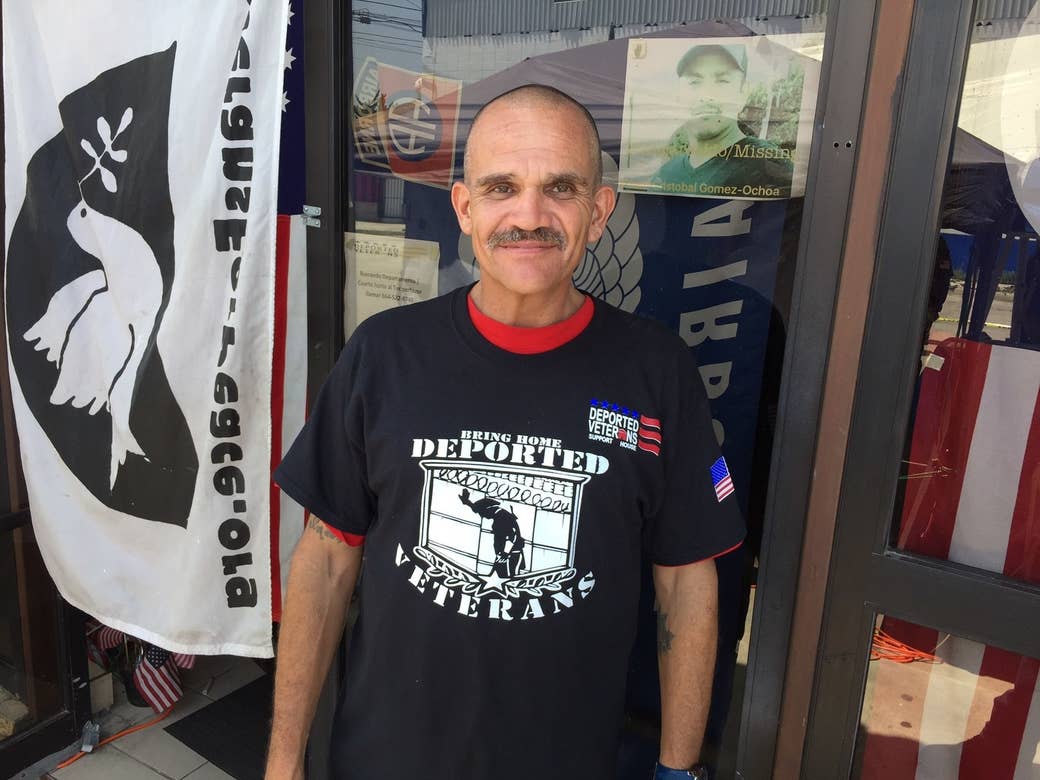

TIJUANA, Mexico — Alejandro Gomez stepped forward from between his brothers in arms. Huddled under a white party tent with nearly two dozen other men, Gomez glanced around nervously, taking in the television cameras, reporters, and the seven members of the United States Congress that had come to meet them — US military vets deported after serving the only country they’d known.

With no mic, he raised his voice to make sure the lawmakers heard his simple message.

“This deportation is unjust,” the 50-year-old ex-Marine said. “It has cost me my marriage, separation from my kids, and my health.”

It was an emotional and surprising moment for Gomez who, after two deportations, had given up on the idea that he’d ever see his family again. And now, seven years after he’d arrived in Tijuana, a delegation from the Congressional Hispanic Caucus was standing here promising to fight for him.

“The fact that seven congressmen and congresswomen made it up here is phenomenal to me,” Gomez said later. “It lifts up my hope. Just talking about it I get goosebumps. Because there’s hope now. You get deported, dude? You lose hope,” Gomez said, his voice cracking.

Gomez and the other men who met with the CHC lawmakers — all border state Democrats from California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas — represent just a handful of the veterans who have been deported over the last 20 years, swept up in raids targeting felons or those who repeatedly cross borders illegally.

“It’s a travesty. We believe anyone who was willing to risk their life for the United States should not be subject to deportation,” Texas Democratic Rep. Joaquin Castro said after the meeting.

“We believe anyone who was willing to risk their life for the United States should not be subject to deportation.”

Danielle Bennett, a spokesperson for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, told BuzzFeed News in a statement that while the agency “respects the service and sacrifice of those in military service, and is very deliberate in its review of cases involving veterans … applicable law requires ICE to mandatorily detain and process for removal individuals who have been convicted of aggravated felonies as defined under the Immigration and Nationality Act.”

And while Donald Trump’s hardline approach to immigration seemingly makes him an unlikely ally, the CHC members believe he’s the exact man to do what President Barack Obama didn’t — stop deporting veterans and bring back those whom previous administrations forcibly removed.

“We’ve got a new president. Everything is going so wrong. Everything is going so badly. This is a chance for him to do something positive,” said California Democratic Rep. Juan Vargas. "Unfortunately, the previous president was not that interested in this issue." Vargas has taken the lead on legislation that would end deportations of veterans, allow for veterans to return to the United States, and provide access to health care for deported veterans living abroad.

“You’re talking about veterans. You’re saying you want to help them. How are you gonna fix the VA? How are you gonna do all this stuff?” Vargas said. “Help these guys. It’s easy — the whole country will applaud you.”

Nobody knows for sure how many veterans have been deported, though as part of a 2016 study, the American Civil Liberties Union was able to identify 239 foreign-born veterans who had been removed from the United States. But those numbers are low. Nearly all of the veterans were identified by aid groups like the Tijuana-based Deported Veterans Support House, where the lawmakers’ meeting occurred Saturday. Activists said they routinely find former service members in Tijuana and other border towns where the US deports thousands of Mexicans each day. In fact, Gomez was one of several men who’d only heard of the Support House, which vets call the “bunker,” last week. Run by Hector Barajas, a 40-year-old Army veteran who was deported in 2010, the bunker provides deported vets with temporary shelter, assistance in accessing pensions and other benefits, and help getting on their feet in Tijuana. It told the lawmakers it confirms the military background of each individual who come there for help.

They include ex-soldiers who served in wars spanning Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan, and most say they came to the United States as children and got green cards before enlisting. Many allege that recruiters either made false promises that they’d receive expedited citizenship or that it would be bestowed upon them when they swore their oath to the military.

In 2002, President Bush signed an executive order that expedited the citizenship process for foreign-born active-duty members; two years later, changes to immigration law allowed naturalization services to occur on military bases outside of the US. But for vets like Gomez who left the service before 2002, or who never took advantage of the expedited process while serving, the process of getting permanent citizenship remains the same as for any other green card holder.

They also all had brushes with the law that led to their deportation. But while it may make them seemingly less sympathetic, all of them served out jail time or probation and believe that given their service, they should get another chance.

“During the Vietnam War, thousands of draftees chose to flee the country to other parts of the world rather than serve their country. They got amnesty,” Luis Vargas, a former Marine, told the lawmakers during their meeting. But in the decades that followed, he continued, “we voluntarily signed and enlisted. We unfortunately broke the law.” Vargas, who said he enlisted in the 1980s, said deported veterans want a chance to “prove to the United States that we can become pillars of society.”

Deported veterans want a chance to “prove to the United States that we can become pillars of society.”

Luis Puentes, 37, came with his parents to the San Fernando Valley area of California when he was 12 years old. Originally from Jalisco, Mexico, Puentes joined the Army after high school and served as a paratrooper.

After a bar fight in which he badly injured a man, Puentes was sentenced to 13 years in prison, where he earned a college degree, worked as part of a volunteer firefighting unit, and, he said, became a changed man. “I did make a mistake when I was younger. But since then, I’ve changed a lot as a person. I’ve gotten a college diploma, like I said, I spent four years voluntarily risking my neck doing wildlands firefighting,” Puentes said.

Puentes was set to be released from prison in January 2017 and had been taking part in a work-release program. One day a few months before his release date, immigration agents came to his work site and took him to a Texas detention facility. Because he wasn’t a citizen and had been convicted of a violent felony, he would be deported.

Puentes was put on a plane to Mexico City on Jan. 18, two days before Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th president of the United States. “I’m just trying to get used to it. Yeah, it’s hard,” he said. “Over here it’s a totally different system, ya know? The laws are different, it’s a different culture, it’s hard, I mean it’s crazy.”

“I understand making a mistake, but I served 12 years. As a result of my mistake I lost my career, I lost the opportunity to be with my kids who I haven’t met. I’ve lost everything. And now I’m here in a different country. I was born here, but I’m an American,” Puentes said.

When immigration officials came for Gomez in 2005, getting deported was the furthest thing from his mind. A truck driver for a southern California tropical plant wholesale company, he was married with four children, living a normal life in San Diego.

But a 1996 crack cocaine charge — for which Gomez had been given no jail time — eventually caught up with him. Although he said his 1996 plea deal included a provision that the felony not be used to deport him, it didn’t apply in federal court. And so Gomez, who’d lived in the San Diego area since he was 6 months old, found himself in Tijuana with no job, no money, and no prospects.

“You get here and you realize the deplorable conditions you’re going to have to live in: Oh my god, this is going to be me for the rest of my life? Are you kidding me?" he said of the experience.

“I was working legit. I was paying taxes.” Now “I live like a scumbag and I make a horrible wage.”

He quickly made his way back to the US and settled back into his life until May 15, 2010. “ICE shows up at my house one morning and dragged me from my bed,” Gomez said. “I was working legit. I was paying taxes. I think that’s maybe how they caught on to me.” It was his wedding anniversary, and it was the last time he’d wake up in the United States.

Two days after arriving in Tijuana, Gomez was arrested in one of the police’s routine sweeps of areas with large populations of homeless deportees. He spent 36 hours in jail.

Now, working as a security guard for 1,400 pesos a week — about $85 — he ekes out a basic existence. “I live like a scumbag and I make a horrible wage. The standard of living is terrible. I mean, just look around,” he said, shaking his head.

Although his wife spent two years traveling to Tijuana to see him, the couple eventually divorced. His adult children won’t bring their families to visit because they fear drug cartels and the area’s perceived lawlessness, so he’s never met his 2-month-old granddaughter, Charlotte. “I have Snapchat. I have Instagram. That’s how we communicate,” he said, wiping away tears.

One of the biggest problems facing deported veterans is access to even basic health care. Danielle Horyniak, a researcher at the University of California at San Diego who is studying the health conditions of deported veterans, said it’s particularly hard on older vets like Gomez, who have chronic physical and mental health problems. Gomez, for example, said he can’t get a better paying factory job because of a chronic back problem that has gone untreated.

“These people fought for the US, put their lives on the line, which causes mental and physical issues. Add that to the issues of deportation, which is very stressful. … So you’ve got all these health issues being exacerbated,” Horyniak said.

Although the Veterans Administration does provide vets living abroad with help through the Foreign Medical Program, there’s a catch — they first have to undergo a battery of examinations by VA doctors.

“These people fought for the US, put their lives on the line, which causes mental and physical issues. Add that to the issues of deportation.”

For veterans in Tijuana, the doctors are tantalizingly close, just 32 miles up Highway 5 at the VA San Diego Healthcare System. But since the vets can’t cross the border, the facilities might as well be 3,200 miles away.

Although Rep. Vargas has introduced legislation specifically designed to address deported veterans’ health care needs, the CHC members are hoping to work with the Trump administration on at least a temporary fix.

The lack of care “is shocking,” said Rep. Michelle Grisham, the CHC chairperson. Grisham, a New Mexico Democrat, said she’s hopeful the Trump administration will agree to begin sending VA doctors to Tijuana to conduct exams of deported veterans, a move that she said would be a welcome “interim step” while a series of bills introduced since March move through Congress.

Of course, that rests on the notion that the Trump administration will be open to either temporary fixes or the broader legislative changes the CHC is seeking. The Trump administration has yet to show any serious interest in bipartisanship, and given the unpredictable nature of the president, nobody can predict what issue might catch his fancy — or for how long. “I can’t exactly say what the president or Congress will do,” Rep. Castro acknowledged.

Still, Grisham said they’re willing to work with the administration on the issue and believe that for a White House constantly beset by scandal and bad news, ending “one of the most shameful acts America has done to its veterans” could be the sort of headline that could catch Trump’s eye. ●