BATON ROUGE — Local black community leaders and activists said they are angered and even alarmed by what they view as law enforcement authorities’ conflation of peaceful and legitimate protests with a gunman’s cold-blooded ambush that killed three officers and wounded three others.

Their comments — and the authorities denial of any such conflation — come in the wake of a wrenching two weeks that included a pair of high-profile police killings of black men followed by the assassination of eight police officers here and in Dallas. They show that the long-running discord between the police and the black community in this deeply divided Southern city is unlikely to end anytime soon.

Activists were responding mainly to comments made at Monday’s emotional press conference, in which Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards and top law enforcement authorities laid out how Gavin Eugene Long, a 29-year-old Marine from Kansas City, methodically carried out his murderous attack.

Baton Rouge Police Chief Carl Dabadie Jr. took the opportunity to defend his use of officers in riot gear, some carrying military-style rifles, during recent protests sparked by the July 5 police killing here of Alton Sterling. A videotape of the 37-year-old black man being fatally shot while pinned to the ground by two white Baton Rouge Police Department officers went viral, and authorities pleaded for peace and calm as law enforcement agencies met — and sometimes clashed — with protesters in the streets. But for six days before Long killed the officers, there had been few demonstrations and zero arrests.

At the Monday press conference Dabadie said: “We've been questioned for the last three or four weeks about our militarized tactics and our militarized law enforcement. This is why, because we are up against a force that is not playing by the rules. They haven't played by the rules. They didn't play by the rules in Dallas and they didn't play by the rules here.”

“I took issue with his attempt to excuse the militarized approach of the Baton Rouge Police Department,” said Dawn Collins, an East Baton Rouge Parish School Board member. “That type of language is disappointing. Sunday’s tragedy is being exploited to continue doing business as usual," she added, saying the governor at least made clear that most protests in town had been peaceful.

The Baton Rouge Police Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Local authorities have said they don’t know if Long was inspired by Sterling’s death, or another gunman’s deadly attack two weeks ago that left five police officers dead in Dallas, or something else entirely. In an online video posted two days before the shooting, Long said, "I just wanted to let y'all know, don't affiliate me with nothing. I thought my own stuff; I made my own decisions.”

In Edwards’ opening address at the press conference, he called Long’s attack “diabolical” but then said something that disturbed many activists: “that is not what justice looks like. It's not justice for Alton Sterling or anything else that's ever happened in this state or anywhere else. It's not justice for anybody. It's certainly not constructive. It's just pure unadulterated evil."

In those comments — as in Dabadie’s talk of “a force” and “they” — activists heard a conflation of protesters with the two assassins. “They’re trying to tag [Micah Johnson] and Gavin Long with the black community,” said Crystal Williams, who founded an organization named North Baton Rouge Matters in the wake of Sterling’s death. “I definitely feel like they’re trying to use this narrative so they can silence our voices.”

“We object to any community leaders who would say that," the governor’s spokesman, Richard Carbo, said, flatly rejecting any suggestion that Edwards has tied protestors to the police shooter. “The governor and I believe a lot of folks have been extremely complimentary of the manner protests have been conducted here.”

But black leaders here said they haven’t heard authorities say that loudly or clearly enough. They're calling for an unequivocal distinction between demonstrators exercising their free-speech rights and murderous madmen such as Long and Johnson.

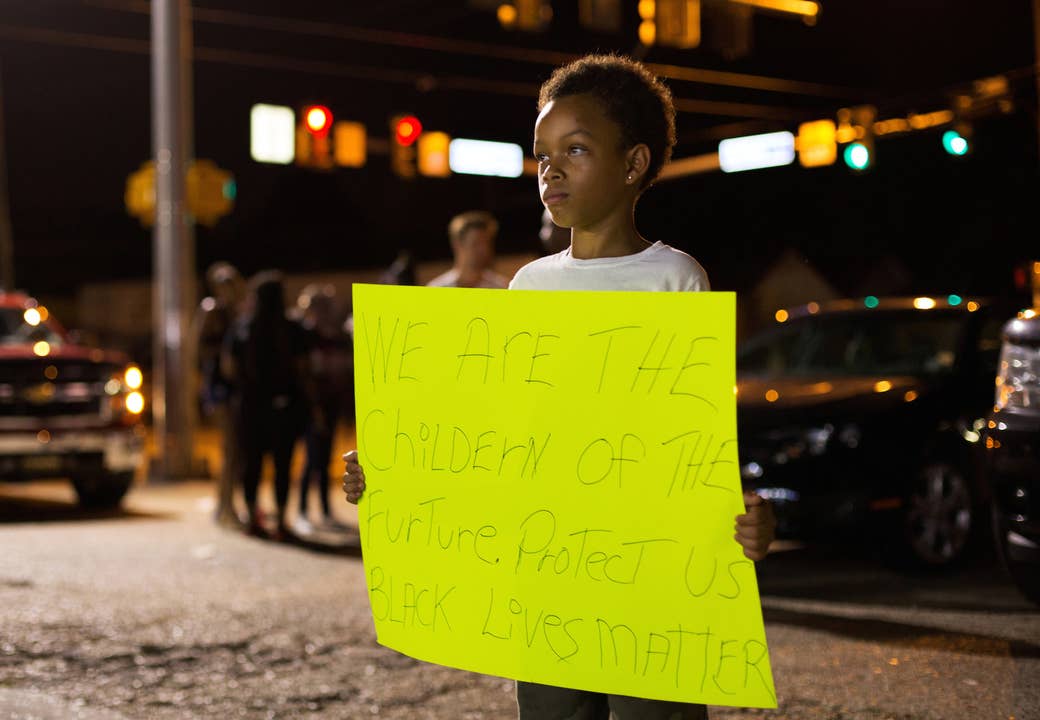

“There’s a difference there that needs to be drawn and publicized,” said Michael “A.V.” Mitchell, who helped organize a recent demonstration for local children. “Protesters are after peace and equality,” he continued. “People who are going to protest don’t go out with a sign and then decide to pick up assault rifle and become expert marksmen.If you’re going to go shoot people, why protest?”

Some activists even said that by not stressing the difference between demonstrators and the police shooters, authorities could be placing protesters in danger from those who might see them as a lethal threat to officers.

“There are already groups out there that are upset with us,” said Williams, the anti-police brutality activist. “And that definitely adds to that agenda on why we should be targeted in the black community.”

In Baton Rouge, public sentiment about the police has swung from accusations of brutality after Sterling’s killing to a surge in support for police, demonstrated by flags still flying at half-mast and “Cops Lives Matter” signs springing up around town. In a Facebook post shortly before he died, one of the officers killed in Long’s attack, Montrell Jackson, gave voice to the divide that still splits this city: the police department’s defensive posture and the racism that many ordinary black men feel.

“I swear to God I love this city but I wonder if this city loves me,” Jackson wrote. “In uniform I get nasty hateful looks and out of uniform some consider me a threat.”

“The community is grieving for the officers that were killed on Sunday too,” Williams said. “In fact the black community can relate. The same fear officers fear everyday because of the danger of their job, the black community feels it everyday from the other end of the spectrum.

At the moment, activists pushing for police reform find themselves in the uncomfortable position of challenging a grieving agency while also shielding themselves from accusations that their anti-police brutality rhetoric has incited deadly violence against police.

Erika Green, a member of the East Baton Rouge Parish Metro Council, suggested organizers put a hold on the protests and wait to hold more substantial conversations with the police.

“If there’s a protest next week, how do you handle that?,” Green asked. “If a protest led by pastors or people who are going to be as nonviolent as possible, will [police] stand by them in military gear?”

She said, “You’re going to have to wait until everybody calms down.”

But Williams promised that that protests won’t stop.

“We are not responsible for” Long, she said. “We are not going to be distracted.”