BALTIMORE — One of six Baltimore police officers charged in the death of Freddie Gray took the stand Wednesday in his own defense, painting himself as a well-intentioned recruit hoping to restore trust in law enforcement in the same poverty-stricken neighborhoods where he grew up.

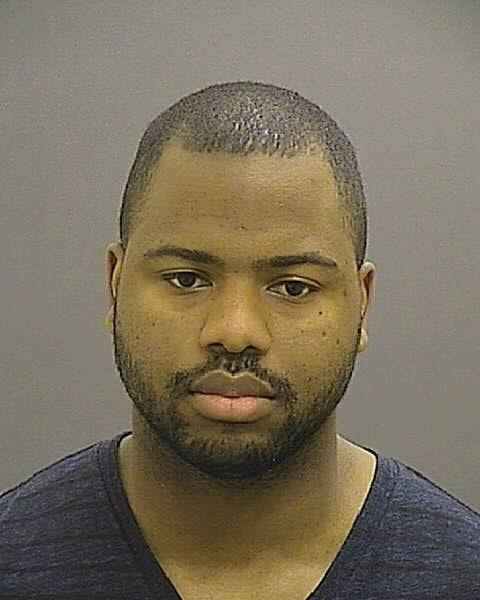

William G. Porter faces charges of involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, misconduct in office, and reckless endangerment in connection with Gray’s death, which occurred April 12 after he suffered spinal injuries in police custody.

Gray’s death set off protests and, ultimately, rioting in West Baltimore thrusting the 25-year-old’s name into a national movement concerned with police violence against young black people, including Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Sandra Bland.

On the sixth day of his trial, Porter, 26, took the witness stand a little before 11 a.m. Wednesday wearing a charcoal-colored suit with a gray shirt and a dark blue tie. He spoke in a clear and confident tone, and looked directly at jurors while under questioning from his attorney, Gary Proctor.

His testimony was the highlight of the longest, most-dramatic day of the trial, which also featured the forcible removal of an elderly black man from the courtroom by three deputies. It wasn't immediately clear why the man, who was sitting a row behind Gray's relatives and could be heard saying, "I'm a member of the family," was taken out of the court — deputies carried him by his head and feet out into the hallway.

Porter portrayed himself as a well-intentioned, empathetic police officer who was hoping to restore trust in law enforcement after being rejected from the Air Force because of color-blindness. He testified that he'd never once fired his gun, or used mace or his Taser since becoming an officer in 2012.

“People had negative views of police,” Porter said. “I wanted to give people a different view to police…I was always fair.”

Porter said would come to know Gray pretty well in his two-and-a-half years patrolling the neighborhood on foot.

“If he wasn’t dirty,” Porter said, a reference to possession of drugs, “he’d come over and talk to me."

"Freddie Gray and I weren't friends," he explained later. "I had a job to do and he did things. But we built a respect for each other."

But Gray also had a reputation among officers as someone who would resist arrest, Porter said. A colleague told him Gray had recently tried to kick out the windows of his patrol car during an unrelated arrest, Porter added.

“He’d actively resist,” Porter said.

“He’d yell?” asked Proctor.

“Yes, he would yell,” Porter responded.

On the morning of April 12, Porter said he was responding to the scene where a man had been arrested after running away from an officer. He could hear yelling in the back of a police van.

After a couple more stops in the neighborhood, Porter approached the rear of the van and noticed Gray was inside, his wrists handcuffed behind his back, his feet shackled, while laying on the floor.

“What’s up?” Porter recalled asking Gray.

“Help,” he said Gray told him.

“How can I help you?” Porter said.

“Help me up,” Gray asked him, according to Porter’s testimony.

Porter then demonstrated for the jury, with an assist from his two defense attorneys, how he lifted Gray off the floor and sat him on the bench in the van’s compartment. He said Gray couldn’t tell him exactly what was wrong with him.

It was then Porter explained that often people under arrest attempt to fake injury or health injuries to avoid going to jail. “Jailitis,” he said they call it. Porter said he didn’t notice any major injuries to Gray, and didn’t read Gray’s increasingly unresponsive demeanor as anything unusual for someone under arrest.

But Porter said he told Officer Caesar Goodson, the driver of the van and one of the six officers facing charges in Gray’s death, that Gray would need medical attention.

“It’s the wagon driver’s responsibility to get him … from Point A to Point B,” Porter testified.

Porter said he didn’t put Gray into a seatbelt, per department policy, because he’d never seen an officer — over more than 150 arrests involving a van in his career — do that before. It simply wasn’t something that was usually done, Porter said.

Throughout the trial, prosecutors have argued that Porter’s failure to place Gray in a seatbelt or promptly seek medical attention means that he bears significant responsibility for Gray’s death. Porter’s attorneys have maintained that he acted to help Gray, implicitly shifting the responsibility for his death to the other officers charged in the case.

Another officer, Zachary James Novak, testified that it would have been the driver's responsibility to call for medical attention or take an injured or ailing passenger to the hospital.

"It's on the guy driving the wagon," said Novak, who was part of Gray's arrest and found him unresponsive with Porter but was given state's immunity to testify.

Porter said he suggested to Goodson that Gray would need medical attention but didn't know Gray was seriously injured. He also said he didn't insist Goodson call for a medic or take Gray to the hospital because they're equals and "I can't tell Goodson to do anything."

Novak, Porter, and defense attorneys also portrayed Baltimore's police department as an agency struggling with limited resources, old equipment, and uneven training and guidelines. As an example, Porter said his time at the police academy in 2012 had actually been interrupted for several months because one of the trainers accidentally shot one of the officers during a training exercise.

But during one of the most-pointed exchanges of the day, Porter became defensive when one of the prosecutors asked him if the police department had a culture of "stop snitching" similar to one that he suggested prevailed in the streets he patrolled.

"It's not," Porter said. "I'm actually offended you would say something like that."