The biggest fear for a projectionist at a movie theater used to be loading reels out of order, or tearing the print. Now, it's deleting the film.

Which is exactly what happened just before a late April press screening for The Avengers. The Twitter dam burst with the flood of 35mm purists snarking about how it's impossible to delete a 35mm print. This is very true; if a physical film print breaks, it snaps or bursts into flames. It's also impossible to create another pristine 35mm print on the spot, which is what the theater staff did for The Avengers — they downloaded another perfect copy in minutes.

Digital conversion and projection is already common in chain theaters across the country, with 27,000 screens in the U.S. (over two thirds) converted to digital. The switch started in earnest last year after major studios like 20th Century Fox privately notified theater owners in December 2011 of the coming new world order. And at CinemaCon this year, Fox's master plan was announced: all digital, no film by 2013.

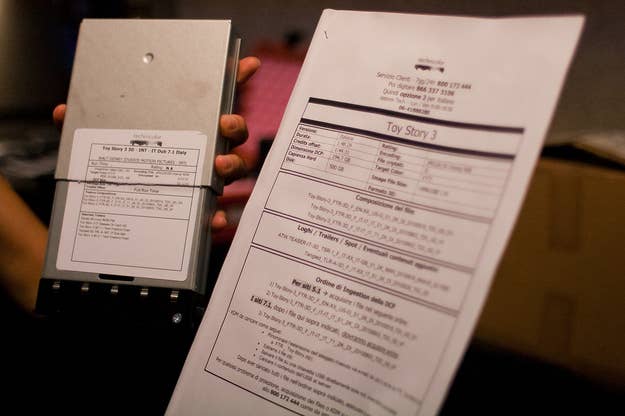

The studios are completely phasing out 35mm prints for Digital Cinema Packages, which are the standard in multiplexes now. Instead of bulky film reels, DCP are essentially encrypted hard drives with audio, video and data that are hooked up to a camera. If you've seen any film in the last three months at a multiplex — especially 3D — you've seen a film in DCP. Major chains, like Regal and AMC, have recently added “D” on certain listings to reveal you've been watching DCP all along.

Cue the downsizing of venerable film processing companies like Technicolor and Deluxe.

There are a few reasons for you, non-projectionist moviegoer, to care about this. The refusal by studios to send out prints will cripple independent theaters or groups that refuse to purchase DCP. Most smaller theaters can't afford the DCP, and soon they won't have prints to screen, either. It’s already happening: If you've been to a midnight screening of Serenity recently, you watched a disc. The fate of the prints is one of quiet assimilation, as they'll likely be digitized and converted into DCP-friendly formats over the next year. As terrifying as this sounds, it promotes a unified quality across the board. Which means what you see in a theater really won't seem that different when it's put onto a Blu-Ray or shown on basic cable.

There's an easy way to figure out if you're watching a restored print on film or DCP. If the transfer isn't handled properly, it'll show up in the final product. The DCP difference can be made clear when blacks are so solidly black that the ghosting effect that plagues HD programming can happen in the theater. Still, regular folks who happily pay $20 for a 3D IMAX ticket don't care about the quality, just the scale — most probably can't even tell the difference between a fake IMAX and a real IMAX theater.

Still, it's a problem for 35mm enthusiasts. "When you go to a movie theater, it should be in a format you can't show in your house," says Julia Marchese, an employee of the New Beverly Theater in Los Angeles and founder of Petition for 35mm. "Why would I pay to see that? I'm going to pay because there's a projectionist making this print perfect for me to see."

Marchese has spent the last year gathering online support through her Twitter and a petition to allow 35mm to remain in circulation. She's even planning a documentary to explore why 35mm is needed.

"Because we've been with 35mm for over a hundred years, it's a reliable format. Digital changes so fast we have no idea where it's going to be in five or ten years. The cost of digital is so much, we're going to lose a lot of little theaters because of that. And if we have to constantly upgrade, it's just going to cost us in the long run," she says.

The same way that some films never made it to VHS and from VHS to DVD, it's a given that some won't make it to DCP restoration and will remain locked in studio vaults. "I think studios, if they had their way, would've done this very sneaky changeover. There were some studios that started to destroy prints," says Marchese.

Still, studios are making the point clear: change or die, Mom and Pop. Bruce Goldstein, director of repertory programming for New York Film Forum says, "Unless you have DCP, there are certain titles you won't be able to show. That's a big problem — for us too! Film itself is going to feel very precious. We're not able to get as many [film] prints as we used to get."

The LA Weekly ran the first rallying cry about the end of film when it discovered that “by 2015, used in a paltry 17 percent of global cinemas, venerable old 35 mm film will be mostly gone." Will DCP truly end the world and be powered by sacrificing puppies and baby sloths? Again, not exactly.

In March, FilmForum ran "This is DCP," a 13 film series curated by Goldstein, to "experiment" with the medium.

"I knew it was inevitable that we'd have to introduce DCP, but I didn't want to just start showing [it] without an explanation or something that would inform the audience what it was," said Goldstein. The series was an overall success for the theater, with Goldstein navigating the differences and expectations of digital projection. But upon finding out that every DCP didn't always conform to a certain standard, he says, "Not every film restoration turns out what we'd like it to be. [On the other hand] some of them are spectacular and can achieve things that would be very difficult to achieve photochemically."

In fact, the conversion process "brings you closer to what the cinematographer" saw, as the original camera negative is scanned, says Goldstein, rather than a print made from a copied negative. It adds depth to the image if done properly — although purists would argue it creates a flattening effect.

Also, the reality is that prints weren't designed to last forever, and they can only be touched up so many times before their age shows or an employee mishandles a print into a $14,000 accident. "We did this to prepare for the future," Goldstein explains. "We have not abandoned film at all. We have a hundred 35mm prints on our summer calendar, mostly archival." The problem lies in the physicality of the prints. Travel, storage and wear and tear wear down the prints until they look like the opening credits of The Wonder Years.

So the irony that purists often ignore when it comes to restored films re-released for theaters is that they are actually performed digitally. (Remember when E.T. was released and Spielberg turned the government agents' guns into walkie talkies?) Regardless, the advent of DCPs are "a huge quantum leap in quality" for multiplexes, says Goldstein. It automates the the job of projectionist and removes most human error from the process. (Though when Take Shelter was released in Australia via DCP, the distributor sent the wrong key codes to “unlock” the film and forced the screenings to be canceled until new ones were issued.)

There's also a last, key point to make here: DCP is impossible without a print to work from. Some directors, like Wes Anderson and Nolan, make conscious decisions to use film in their work. Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom, which opened at Cannes yesterday, was shot on 16mm and will be shown in 35mm. But it's an expensive point to keep making, especially when splicing and editing physical film is being phased out when shooting an entire film on a Canon 7D, like Lena Dunham's Tiny Furniture, is possible. It may be the format everyone has grown up with for the last hundred years, and it maybe that it's being replaced as if nothing happened in between.

But we've been digital for a while now. It's time we accepted it.