There are new global figures on female genital mutilation — also known as female genital cutting, or FGM — and at first glance, they're cause for concern.

Numbers are a tricky business. UNICEF's new estimates include data from 30 countries where FGM is practiced, and the numbers are only included if they're good enough to be considered nationally representative. So this is basically a scientifically-backed really, really good guess.

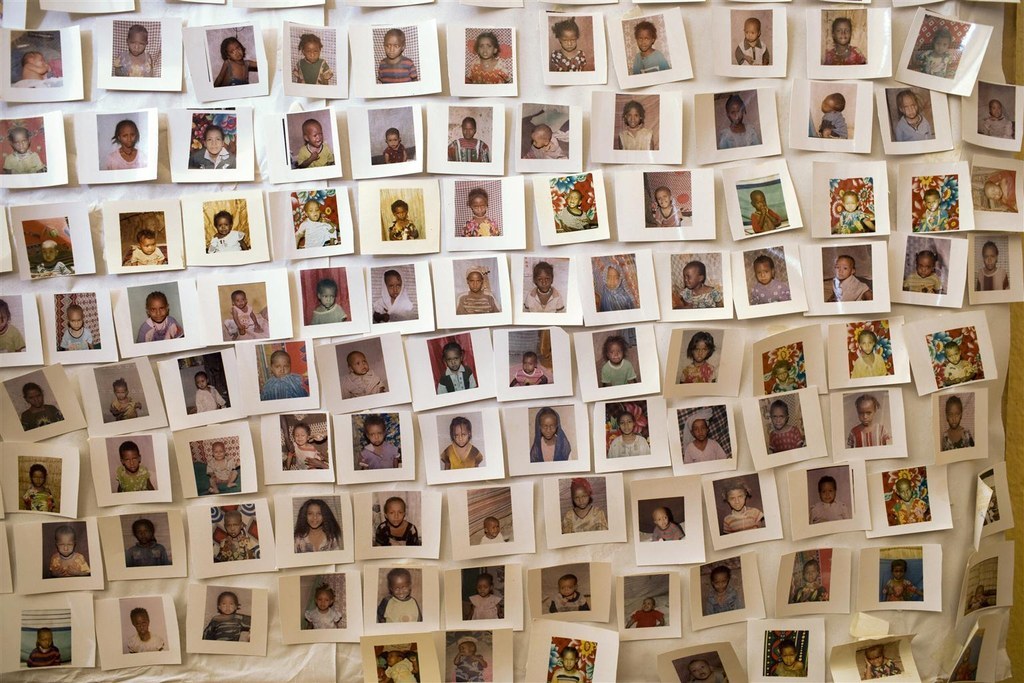

UNICEF's new figures, released today, say that 200 million women and girls have been cut worldwide. That's almost 70 million more than last year's figures.

Those are national figures from various sources, and they don't include estimates by countries like the United Kingdom or the United States. A new report from Plan UK said British doctors reported finding more than 2,000 previously unrecorded cases of FGM among their patients in a five-month period last year.

A half-million girls in the U.S. are at risk for FGM, according to figures released last year, even though it's illegal — especially if their families want to take them back to their home countries to be cut.

And let's be clear about one thing up front: Many of the countries where FGM is practiced have large or majority Muslim populations, but FGM is not a religious practice, and nothing in the Qu'ran sanctions the cutting.

But it's a little more complicated than it sounds. The figure went up so much this year because Indonesia is included for the first time.

The country only started collecting data on FGM in 2013. Tanya Sukhija, a program officer who works on Indonesia for the international advocacy group Equality Now, said the data collection was in response to increasing international scrutiny, including from United Nations human rights bodies.

"Getting that data... is a great step forward," she said, "but it's not enough. That medical professionals are still performing so much of it is really detrimental [and risks] legitimizing the practice there and elsewhere."

More than half of the procedures performed in Indonesia are done by doctors or other medical professionals, according to UNICEF's figures.

In 2010, the World Health Organization, in conjunction with 13 other key global players, issued a strategy to stop health workers from assisting in FGM. But in Indonesia, the government explicitly encourages parents who want their daughters cut to go to doctors, Sukhija said.

Sukhija said there's no evidence that medically performed FGM is any safer; many of the complications from FGM show up later in a woman's life. But any perception of "safer" FGM also misses the point, she said: "Even when medical professional is performing it, it's still a human rights violation."

Also, the figures are going up because the overall population in the countries being measured is going up.

But if you take the long view, there's also some good news. Globally, FGM has gone down 14% since 1985. In some countries, like Kenya, the drop has been even more dramatic.

The Kenyan parliament outlawed the practice in 2011, and national and local leaders have followed up with ground-level initiatives, including prosecutions, that seem tob e making a difference.

"You know none of all this is going to work unless we see the sledge hammer o fjustice that goes after people who do it," said Siddharth Chatterjee, representative of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) in Kenya. "I think what Kenya has demonstrated is political will, and I think that's a major driver of the shift.

UNFPA has led a series of initiatives to reduce FGM, including educational and awareness programs and "alternative rites of passage," which offer communities options other than circumcision for marking a transition from youth to adulthood.

The figures even bring good news from places where the headlines are almost never good — like the Central African Republic.

Embroiled by fighting since a coup in 2012, and one of the world's poorest countries even before that, the Central African Republic has had a notable decline in prevalence, said Claudia Cappa, the lead researcher on the new UNICEF report.

Unfortunately, though, it's not because of any notable intervention. "Our hypothesis is it's linked to conflict," Cappa. "It's known that in conflict, social ties tend to loosen up as a consequence of movement or destruction, and FGM is part of a social norm."

The same thing may account for some the 41% drop, since 1985, in FGM in Liberia, which went through almost constant conflict from 1989-2003, she said.

There's also a warning: UNICEF says it's possible that the gains made in the last three decades could be wiped out as global population increases.

Right now, 1 in 5 girls are in an FGM-prevalent country, Cappa said. By 2050, that number could hit 1 in 3. And most of the countries in question aren't experiencing a rate of decline in FGM that can keep up with that rapid growth, even by the most optimistic estimates.

One of the worst-case scenarios is Mali, in West Africa. "Mali has one of the fastest-growing populations in Africa," Cappa said, and when you take all the factors into consideration, "the number [of women and girls who are cut] is destined to practically double."

Unless, of course, there's more effort to stop the practice. Ending FGM by 2030 is one of the Sustainable Development Goals, the UN's new blueprint for global progress.

According to UNICEF, five countries have criminalized FGM since 2008. That's an important step — but it's also no guarantee that things will change.

In Egypt, nearly 90% of women and girls over age 15 have been cut. Egypt criminalized FGM in 2008, but it's only prosecuted one person, a doctor, who was initially acquitted of the crime.

Molly Melching, who has been working on FGM issues in Senegal since 1997, said community engagement is even more important than laws or national political will.

Melching founded Tostan, which engages community members, religious leaders, and village chiefs and elders in discussion about impact of FGM on the health and well-being of women and their families and marriages. In nearly 20 years of grassroots engagement, just under 6000 communities have publicly pledged to end the practice. (An independent UNICEF evaluation found 70% adherence to those pledges, she said.)

"[T]he law in itself cannot really end the practice. What can really help is when there has been this education and people understand, and then they can use the law to support their efforts to reach out and help others to understand why abandonment is so important," she said.

Laws can also lead to a false sense of decline. "Researches come and say, 'Have you cut your girls?' and people are afraid to say they have, because they are worried they might be arrested or that there might be [other] consequences," Melching said.

Cappa, of UNICEF, said that problem can even influence big surveys like the ones behind the latest report. "At end of day, women are influenced by what they hear around them, particularly in countries with severe punishment," she said. (UNICEF in the past has explained in its reports where it suspects this bias may influence data, she added.)

Dr. Abdul Giama, a Somali gynecologist working in Galkayo, told BuzzFeed News last year that national international efforts, especially those that prioritize legal norms, can miss the point.

"We've spent a hell of a lot of money, time, resources on FGM but…the real problem is [the] taboo," he said.