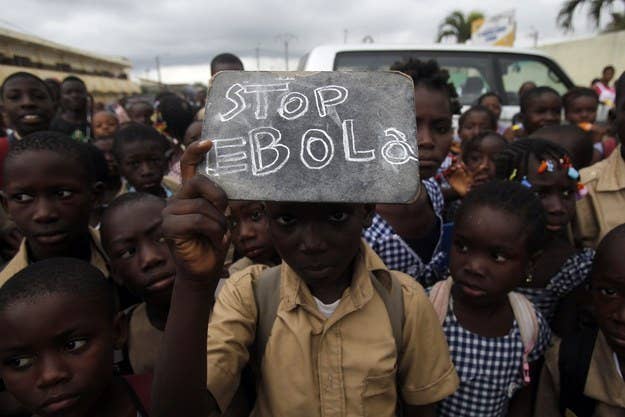

NAIROBI — When the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released its first scientific report on the ongoing Ebola outbreak in West Africa, one — massive — number caught everyone's attention.

If nothing changes, and if the CDC is right that there are more Ebola cases than the regular reports are counting, then West Africa could have 1.4 million cases of Ebola by Jan. 20, the government health body said.

It's a staggering number, far bigger than anything the health authorities in three countries at the center of the outbreak — Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea — had been preparing for, bigger even than the biggest warnings late last month, and again on Tuesday, from the World Health Organization (WHO).

So where does the number come from, and how did it get so high?

The CDC was trying to estimate what public health officials call underreporting, a common phenomenon in which any given disease or health ailment affects more people than actually seek treatment for — or "report" — the ailment.

Health officials inside and outside West Africa have long understood that Ebola is being underreported. The numbers everyone knows — which right now stand at more than 6,000 infected and nearly 3,000 dead — come from the WHO, which relies on cases reported to them by the national ministries of health.

But not every Ebola case is recorded by the health ministries. In Liberia, for example, Ebola patients are turned away from clinics that don't have the right equipment or isolation facilities to care for them, and the country has never had enough beds in its specialized Ebola treatment anyway. Its labs, too, have had too little capacity to confirm cases as rapidly as they appear, making the Health Ministry's figures lag behind, even though they are updated daily.

The disease itself, meanwhile, sparks fear among the family and neighbors of the sick. Ebola is a quick and almost-certain killer — a new WHO study puts the mortality rate of this outbreak at 70%, far higher than earlier figures — and treatment protocols require patients to be isolated from family and cared for by nurses in plastic body suits. It's been common for some families care for or bury their dead in secret, rather than subject themselves to emotionally painful and psychologically frightening treatment protocols.

These are just some of the reasons scientists suspect that the official figures are too low. But as the speed of the outbreak has intensified in the last few weeks, estimating just how low the official figures are has become crucial — not just for understanding the scale of the medical response, but also for galvanizing a political response.

The CDC began work on this study in late August, after a CDC staffer in West Africa asked a research team at the center's Atlanta headquarters to come up with estimates "so that we can help the [local] ministry of health think about urgency but also have a story to tell the international community about why they needed, at that time, more resources," Dr. Martin Meltzer, the lead author of the study, told BuzzFeed News by telephone from Atlanta.

Meltzer and his team built a model that estimates how many new cases the region might see, depending on when certain levels of intervention are offered. The model is based on data from up to late August — before American and British military aid was pledged, and before new Ebola treatment units opened in Liberia — and like any projection, it offers a range, not a single number.

On the low end, the study said, the region would see 550,000 more Ebola cases if nothing changed. On the highest side of the high end, it estimated 1.4 million.

But even Meltzer says actually reaching 1.4 million cases is unlikely — and not just because the dismally slow global response is finally starting to speed up.

"We're getting hints of data, though it's not been confirmed, that people are changing their behavior toward less risk of onward transmission," Meltzer said.

The study, like all such studies, outlines its assumptions and limitations. "We clearly state, 'Beware, we've used this, but it might not be correct,'" Meltzer said.

Researchers outline their assumptions because data is not perfect, and in cases like this Ebola outbreak, it can even be difficult to get. In some cases, a research team has to approximate unavailable information with information that's similar — imperfect, perhaps, but available.

And that's how the CDC came up with 1.4 million.

Meltzer knew that the best way to find out how many cases of Ebola aren't reported would be a house-to-house survey, but that's not possible right now, nor would it be the best use of resources.

So he decided the best way to estimate underreporting would be to think about the number of beds actually in use in the region on a given day, and to compare that with the number of beds needed. He couldn't get reliable figures for beds in use in Sierra Leone, so he relied on an estimate by colleagues in Liberia about the number of beds that had patients in them on a single day in late August.

Meltzer found that the number of beds in use was 2.5 times lower than the number of beds his model said Liberia needed (and his model's estimate of how many beds are needed is also, of course, subject to assumptions and possible error).

And that meant to Meltzer that his basic projection — 550,000 cases by Jan. 20 if nothing changes — was likely to be 2.5 times too low. So he multiplied his first projection by 2.5 — he did what scientists call "correcting for underreporting" — and he got 1.4 million (after a little bit of rounding).

And, like any good numbers guy, Meltzer is the first to concede the worst-case estimate for both Sierra Leone and Liberia might be wrong.

"We want[ed] to alert people to the fact that there was underreporting. People state it, but I don't think anybody had written down a number. This is a first go at it ... The intention was to start the conversation about what the ground-truth number really is," Melzter said. "We're not insistent in any way that this is the number fixed in time and place forever. This is not about pinpoint accuracy. It's more about the concept."

There are lots of technical reasons any estimate may be wrong, but there are some on-the-ground reasons that Meltzer's proxy — how many beds are in use standing in for how many cases aren't reported — may be problematic.

Liberia has never had enough beds for its sick patients, but that doesn't mean all the sick patients without beds aren't being counted in official estimates. Meanwhile, Sierra Leone received most of the international assistance, in terms of international staff and treatment facilities, in July.

For instance, there were 550 staff from Doctors Without Borders in Sierra Leone that month, and they were running a 100-bed treatment facility in one rural county. In Liberia, the only international response team was preparing to pull out after its staff caught Ebola, and health officials were warning that contagious patients with Ebola symptoms were sitting outside the only treatment ward in the capital, which had just 25 beds.

So bed availability has been uneven across the two countries, and in Liberia in particular, there has always been more demand for beds than there is supply.

Couldn't these circumstances affect the accuracy of the estimate?

"Absolutely," Meltzer said.

But even if the estimate that grabbed headlines was always unlikely, Meltzer said the number served its purpose.

"The bigger number … showed the world, particularly the international community, why we need to focus and provide more resources," he said.