KIGALI, Rwanda — At first glance, Seraphine Mukakinani’s life seems unremarkable. She didn’t finish school, so she sells clothes or fruits or whatever's around at a small market, which doesn’t bring in much. Usually, she wraps herself in kitenge, that brightly colored “African cloth,” and in secondhand T-shirts. A single bulb lights half of her two-room house, on a road that rings Nyamirambo, a busy, crowded neighborhood in Rwanda's capital city of Kigali. For water or cooking or the toilet, she goes outside.

Nothing about this is exceptional, so you’d be forgiven for not realizing that Seraphine is one of the most influential women in the world.

“Recently, a police officer came into the house to check for drugs,” she said. The officer was conducting a routine spot-check, and he took an interest in a small bundle on a shelf in Seraphine’s bedroom. “‘What is that?’” she remembers him saying. “‘Bring that here.’”

“I opened it, and he got surprised,” Seraphine said. “There’s a picture of me and the president!”

Seraphine rocked with laughter when she remembered the look on his face.

“He said, ‘Umukecuru! Where did you meet our mzee?” Old woman! Where did you meet Big Man?

Seraphine had met him at the screening of a film that tells her complicated, painful story: She survived the 1994 genocide, when an estimated 800,000 people of Rwanda's Tutsi minority group were killed by people in the majority Hutu group. The genocide spread from the capital of Kigali across the country in only 100 days, but the killings happened in waves, at different times and for different durations in different places.

In Taba, a village about an hour's drive from Kigali, the killings came quickly, and with them, a kind of crime long considered unspeakable: Hundreds of women there — and possibly hundreds of thousands across the country — were raped by members of the interahamwe, the youth militia of a Hutu political party, which did much of the killing.

The genocide ended in July 1994. Approximately two years later, lawyers for an international court set up to try high-level perpetrators came to Taba and gathered evidence. Seraphine and dozens of other women — including her sister, Victoire Mukambanda, and a young woman called Cecile Mukarugwiza — told them about being raped.

That part of the story didn’t initially interest the court, which was narrowly focused on connecting local and national leaders to the killings. But eventually, Seraphine, Victoire, and Cecile found themselves at the center of what became one of the most important human rights cases in the world: Their stories would help convict a man for rape as a crime against humanity for the first time in history.

“They told us we had strong testimonies, but they didn't really ever tell us why us,” Seraphine said, referring to the five women who testified at the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania, in 1997. (Two have since died.) “We were five women from Taba commune. We didn't know much about laws; we weren't educated enough. We were only supported by the truth.”

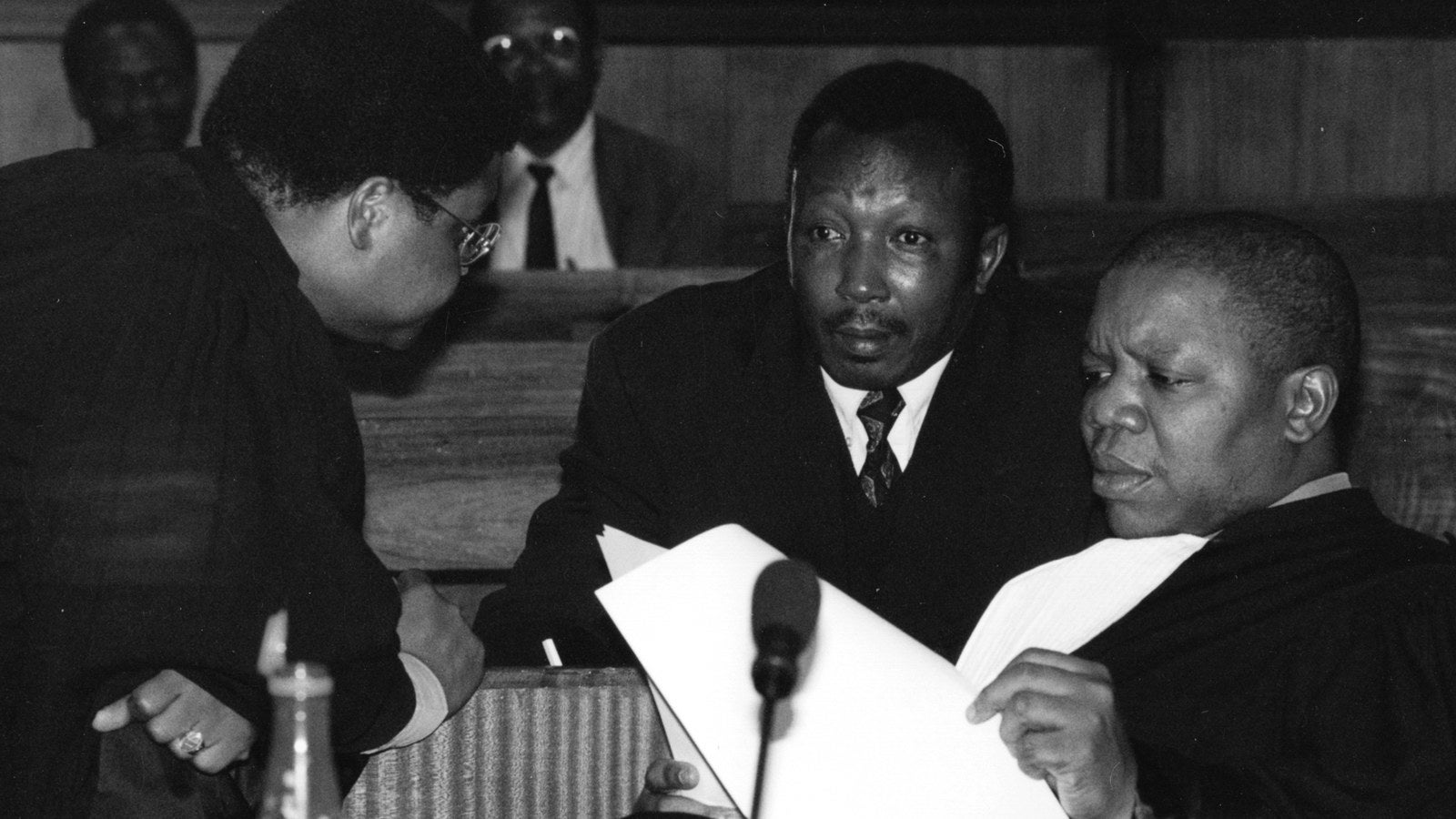

A new documentary called The Uncondemned explores the trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the mayor of Taba. On the strength of testimony from Seraphine and the four other women, Akayesu was convicted of two charges of sexual violence, along with nine other genocide-related charges.

The conviction was groundbreaking. For millennia, sexual violence had been considered unfortunate but not uncommon — a “thing men do” in war. In a ruling that recognized that sexual assault is about power, not about sexual gratification, the ICTR established rape as a crime against humanity and — in possibly its most powerful legacy — as a form of genocide.

But when filmmaker Michele Mitchell delved into the details, she realized that the Akayesu case wasn't a straightforward victory for women's rights. That story took an even more surprising turn earlier this year, when a UN judge tried to block Mitchell’s film, in the name of protecting the witnesses who appeared in it.

Twenty years after one of its biggest victories, the UN court was still fighting about the same thing that nearly derailed the case in the first place: Who gets to decide when women are allowed to tell their own stories?

None of the witnesses ever imagined, in the months after the genocide, that judges and lawyers at an international court would be interested in what happened to them. None of them could imagine telling the story of being raped — so many times, often in front of their neighbors and families — or finding words to explain it to someone who hadn’t been there.

Actually, in those early days after the genocide, in late 1994 and 1995, the women who would become witnesses couldn’t imagine ever talking again at all.

“I was so destroyed. I couldn't even speak. Every time I tried to speak, it felt like my heart was going to break,” Cecile, now 37, said at her home outside Kigali. “I don't know if I can explain it. It's like everything was damaged in the brain. Your mind is tied up, and your voice is stuck inside.”

Victoire, the oldest of the women to testify, said that after the genocide, she felt broken. She had been raped repeatedly, with her baby next to her; the baby was later killed. So was her husband. When it all ended, she had nothing left — no reason at all, she remembers, to speak.

“I would sit and just break into tears without anyone beating me, no one harming me in any way, just tears. I couldn't cook for myself. I would forget to eat. I would just sit, silent, crying all the time. That thing ruined our hearts, our bodies, even our intelligence, our ability to think,” she said.

The court recognized sexual violence is about power, not about gratification.

Victoire didn't say a word for months. Then she attended a meeting organized by a woman called Godeliève Mukasarasi. Mukasarasi, who’d worked as a social worker before the genocide, set up an organization for survivors in Taba, called Sevota. Its support groups became well-known near the capital, and government officials and other important people would come to visit with the survivors. Sometimes, they'd bring them a chicken or a goat, a small but crucial gesture of support.

It was a goat that brought Victoire her voice back. “If you have a goat, you have something. You can take it outside to eat. You can talk to it. You can shout at it. Even if you're shouting and chasing it [as it's running away], at least you're opening your mouth.”

Not long after the women found their voices again, the court investigators found the women. The ICTR was opened in November 1994, and its job was to try high-level perpetrators — government officials, journalists, members of the military — for the genocide. But many Rwandans — lower-level perpetrators, genocide sympathizers, or others afraid of what punishments might come down on them or their families — didn’t want the court to succeed. It quickly became dangerous for people to collaborate with court investigators. By September 1996, at least 10 witnesses had been killed before they could testify in Arusha, presumably to stop their truth from coming out.

One of those killed was Mukasarasi’s husband, who was murdered in Taba just before Christmas 1996. In January 1997, a Hutu woman from Taba was murdered after she came back from testifying against Akayesu; her husband, her four children, and three other kids who happened to be at her house were also killed.

But Seraphine, Victoire, and Cecile overcame their fear and testified because they believed it was important; they believed God would protect them if they told the truth; and they believed, at that moment in their lives, only two years after the genocide, that they probably weren’t going to live much longer anyway.

“For a long time, I had that sickness of being so hopeless,” said Cecile, who was only 15 during the genocide. “I thought, I might die now, or in a few hours, or maybe tomorrow. At any time, something can go wrong, and I’ll die. That was my life every day.”

Originally, Akayesu wasn't even charged with rape. Not because there wasn’t evidence that mass rape had happened, but because, as Mitchell’s film shows, at the beginning investigators didn’t — wouldn’t — spend time building up that evidence for trial.

“If you look back on it, rape had been very well-documented at that point. There was no lack of information that rape was a very big issue,” Jessica Neuwirth, who worked as a special expert on sexual violence for the ICTR and drafted the Akayesu judgment, told BuzzFeed News. “The fact that it wasn’t in any of those [original] indictments was very problematic.”

Early on, sexual violence wasn’t seen as an issue big enough to win the attention or other resources of a financially strapped, overworked team of investigators, prosecutors, and other court officials. Mitchell’s film tells the story, from the prosecutors’ point of view, of how Akayesu was eventually charged with sexual violence.

Akayesu was the mayor of Taba (today called Kamonyi). Mayors are powerful and revered figures in Rwanda, and when the killings in Taba began, Tutsis ran to Akayesu’s office, called the bureau communal, hoping for safety. But they were chased out of the bureau communal by militias who, after a few days, began raping women and girls.

Cecile was one of those girls. “Imagine, I was only 15 — I didn't even have my period yet — [and] being raped by that many men,” she recalled recently at her home, north of Kigali. “And it's in public, in front of people you know.

“They start maybe two, then maybe tomorrow there's 10. One leaves, and the other is there — it's like they are all the same — and the last one says, ‘Instead of getting my penis dirty, I would rather use a tree,’” she remembered.

“There were kids around who started throwing small rocks … so everyone left,” she said. Ironically, if the rape hadn't been public, Cecile might not have been saved. “I remember one lady, she was raped until she died,” Cecile said.

Cecile’s story is similar to so many others from Taba. In 1996, a landmark Human Rights Watch report documented many stories of sexual violence — and spurred the ICTR to review its own work. The tribunal sent a gender consultant named Lisa Pruitt to investigate whether witness statements could support sexual violence charges against Akayesu.

Pruitt, whose story is a key part of Mitchell’s film, came away convinced that court investigators had largely dismissed the issue, discrediting survivors for spurious reasons and focusing narrowly on genocide, which they thought was the more important crime. “Many of the investigators said, ‘Well, we can’t be concerned about some women who got raped. We can’t divert resources to investigate those crimes. We had a genocide down here,’” Pruitt recalls in the film.

She presented her findings to the Office of the Prosecutor in The Hague, the headquarters for the tribunal, but she was told there was no interest in pursuing rape charges after all. Pruitt’s work was essentially buried.

As the film tells it, as far as the prosecutors preparing the case in Rwanda knew, there was nothing linking Akayesu specifically to the sexual violence generally committed in Taba. “[It] wasn’t enough to say, ‘Women were raped in Taba, therefore Akayesu should be prosecuted.’ It’s not that simple,” Pierre-Richard Prosper, one of the prosecutors, says in the film. “We had to prove Akayesu knew, allowed it to happen, did it himself or whatever it may be, and therefore should be prosecuted.”

But in the middle of the trial, in March 1997, one witness testified about the sexual violence she saw at the compound where Akayesu was in charge — testimony that made it possible to connect the man on trial to the rape crimes everyone knew had happened.

“She said, ‘Then I saw the women being dragged to the back of the bureau communal, and I saw them being raped,’” Prosper recalls in the film. “Whoa, hold on. You saw this? She said, ‘Yes. I saw women being raped.’”

“This was potentially a game changer,” Sara Darehshori, also a prosecutor on the case, recalls in the film. “That was always the missing link: Rapes at the bureau communal would have been something that Akayesu couldn’t have missed.”

Eventually the prosecution team uncovered Pruitt’s memo, and that helped lead them to Cecile, Seraphine, and Victoire — until the film known only to the world by their court pseudonyms as OO, NN, and JJ. In June 1997, prosecutors added sexual violence charges to Akayesu’s indictment and prepared to prove that even though Akayesu hadn’t raped anyone himself, he’d known that the militias were dragging Tutsi women away to assault them — and he’d had the power to stop them.

Mitchell’s film focuses on the prosecutors’ memories, but experts who worked at the tribunal say the court’s lone female judge was also influential.

“If a female judge experienced in women's issues had not been sitting on the bench in this case, there would have been no gender crimes prosecuted, as they weren't included in the original indictment,” said Kelly Askin, co-editor of Women and International Human Rights Law and a former legal adviser to the ICTR. “[She] invited the prosecution to consider amending the indictment to include sex crimes.”

That judge was Navanethem Pillay, a South African jurist and the first nonwhite woman appointed to South Africa’s High Court. Pillay left the High Court to join the ICTR, where she was the only female judge for four years. Court transcripts from March 1997 show that Pillay zeroed in on a witness’s disclosure about sexual violence to interrogate possible links to Akayesu.

“There’s a key moment in the transcript, [after] that heavy information gets dropped … and nobody says a thing about it until Pillay raised a question,” said Neuwirth, who wrote the verdict. “What you see right there is that the judges picked it up, not the prosecutors ... If [Pillay] hadn't asked those questions, I don’t think anything further would have happened.”

The indictment was amended in June 1997, six months after the trial began, and three charges of sexual violence, including rape, were added to Akayesu’s indictment for genocide. “One thing Judge Pillay always says is that he was most upset about the [rape] charge,” Neuwirth remembered.

On the strength of testimony from Seraphine, Victoire, and Cecile, as well as two other women whose names remain undisclosed, the court found Akayesu guilty of rape as a crime against humanity — the first time that had ever happened. The court also determined that rape itself could be an act of genocide, a finding that had immediate influence in another international court for war crimes in the Balkans.

It would be hard to overstate the meaning — and continued relevance — of the Akayesu verdict. “Before Akayesu, there was debate about whether rape was even a war crime or merely an inevitable consequence or side effect of armed conflict,” said Askin, “After Akayesu, rape and other forms of sexual violence were taken far more seriously.”

The case has had reverberations in courtrooms large and small around the world, Askin said. International war crimes courts for Sierra Leone and the former Yugoslavia, and cases at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, have all cited the Akayesu conviction. “I was in a very remote village in eastern [Democratic Republic of] Congo, at a mobile court trial, when a judge cited Akayesu,” Askin recalled.

But some of the challenges the Rwanda court faced 20 years ago repeat themselves today, in other war crimes investigations. Neuwirth, today the director of Donor Direct Action, where Pillay is on the board, has since consulted on sexual violence matters for other international courts and said it’s still common for prosecutors to overlook rape and other forms of gender violence.

“I’ve seen this happen again and again in criminal tribunals, where they have to amend the indictment,” she said. “A very common problem is that the evidence isn’t there. In fairness to prosecutors, if you don’t make this special effort, you won’t get it. It’s hard to talk about it. If you’re insensitive to that, if you’re sending male investigators, if it’s not part of their mission — you’re probably not going to get [the evidence].”

Testifying, it turned out, also began a local transformation — for the women who went to the court, and for Rwanda. The Akayesu case helped women in Rwanda push to get rape taken more seriously by Rwanda’s gacaca courts, the local tribunals that, from 2005 to 2012, tried hundreds of thousands of perpetrators in front of their own communities. Initially, gacaca categorized rape as a lower-level crime, in the same grouping as looting or the destruction of property. But, emboldened in part by the Akayesu conviction, women pushed to make rape a “category one” crime, in the same grouping as murder. They won.

Today, Seraphine, Victoire, and Cecile feel proud of all this. Their once-secret identities as court witnesses have become so integral, over the last two decades, to how they see themselves in everyday life that Seraphine and Victoire, the sisters, often drop their birth names and call each other by their courtroom initials. “We usually use our stage names,” Seraphine said with a laugh.

They also feel proud of how far Rwanda has come — a country they consider, above all, safe — and they were almost giddy in the weeks before The Uncondemned was set to premiere, in mid-October, at the United Nations in New York.

So they were shocked — and angry — when officials from the court where they’d testified 20 years ago tried to gag the film that told their story.

Officially, the court was worried about witness protection, which is always a concern in sensitive cases. In June 2016, Judge Aydin Sefa Akay issued a court order prohibiting any screenings of the film because it disclosed witnesses’ identities without the court’s permission and therefore, in the judge’s view, violated witness protection measures.

This line of logic annoys all three of the women, who believe the court had no idea whether they’re safe or not.

“Since 1997, no one [from the court] has come back to me,” Victoire said. “I gave them what they wanted, and no one came to my home, nothing. They promised to follow up, to follow our lives, but no one came back. Not until the movie came out.”

It’s been so long, in fact, that the court doesn’t even exist anymore: The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda formally shut down last year. It’s been replaced by a smaller office, the Mechanism for the International Criminal Tribunals, known colloquially as “the Mechanism,” which oversees any ongoing tribunal business.

“I didn't like the way they treated us. It's like you're a commodity — like you're something they can get whenever they want.”

The Uncondemned isn’t the first time these women have spoken with journalists, but it is the first time they’ve ever used their real names or shown their faces on camera. Michele Mitchell, the filmmaker, told the judge she had written permission from the women to disclose their identities, and that she also had videotaped verbal permission. But the Mechanism hadn’t given permission to anyone to disclose the women’s identities – including the women themselves — so it launched its own investigation.

In late May, witness protection officers interviewed the women in Kigali, in an experience all three women recall as an interrogation.

“They took us by surprise. They just called us suddenly. When we went [to meet them], they separated us and started asking us questions — the whole day,” Seraphine said. “It was like we were vulnerable. We felt helpless.”

After six or seven hours of questioning, the women were asked to sign a paper. They experienced the request as an ultimatum: Revoke your participation in the film, they said they were told, or rescind your witness protection.

In practice, the women say, that protection isn’t tangible — “They don't even know where we live,” Seraphine said with a shrug — but the witnesses prefer being protected, even in theory, to being formally abandoned. “We refused to sign that our security gets removed,” Seraphine said. “Who can sign that?”

So the women chose what they felt was their only option: pulling their identities from the film. Or at least, that's what they think happened. The paper they were given to sign was written in English, which none of them read. “I didn’t understand anything written there,” Victoire said. None of them did, they say, and they were not offered copies. (The MICT declined to comment.)

Mitchell, the filmmaker, had some sympathy for the Mechanism’s concerns. “If all the judge has in front of him are statements saying, ‘We don’t want to do this,’ I imagine he would be alarmed,” she said. But she doesn’t actually know what the judge had: Her lawyers were denied access to the records, for witness protection reasons.

Mitchell said she gave the Mechanism years’ worth of emails detailing collaboration between herself and the tribunal, as well as copies of the written and verbal permission of the witnesses. These did not resolve the matter, but Mitchell proceeded with her film. So in July, the Mechanism also began investigating her, for contempt of court.

Ousman Njikam, spokesperson for the Mechanism, said the proceedings against Mitchell and her film sought to resolve a conflict between freedom of expression and protection.

“There’s a balance that has to be found. Obviously no one wants to deprive anyone of their rights to express themselves freely, but it becomes a challenge … when the Mechanism has an obligation to protect you,” Njikam told BuzzFeed News by telephone. “It’s not an obligation you can defer to someone else. If something goes wrong, we can’t just say, ‘Well, they decided to expose themselves … tough luck.’”

By November, though, that’s exactly what the Mechanism would do.

The fight between Mitchell, the Mechanism, and the women continued through the summer of 2016. The Mechanism argued that it was only trying to act in the best interest of the witnesses. “I’ll give you an example of a kid you have to take care of,” Njikam said, “and the kid who wants to cross the road, but you see an oncoming car. Even if the kid doesn’t appreciate that you want to stop him or her from crossing [in their] own interest — you see the point I am trying to make?”

But the women saw it differently. They felt harassed by Mechanism officials’ repeated calls and requests to meet again. Cecile pretended to be sick; Victoire simply stopped answering their calls.

“[They] treated us like we'd done a huge crime,” Cecile said. “It really, really annoyed me, so much … Also, I didn't like the way they treated us. It's like you are material, a commodity — like you're something they can get whenever they want, ask you questions whenever they want.”

Cecile was also annoyed because the Mechanism’s concern seemed false to her. It never acknowledged that simply participating in the trial all those years ago had already exposed the witnesses, at a far more dangerous time in the country’s history. All of the women described living in close quarters in refugee camps 20 years ago, when ICTR staff interviewed them. “People knew who they are. [ICTR staff] had been coming to talk to us,” Cecile remembered. “[Neighbors] knew we were going to testify.”

The women were also frustrated that the Mechanism didn’t seem to notice how Rwanda had changed. Today, Rwanda is peaceful, and it's common for survivors to speak publicly about what happened to them during the genocide. “These are things we've been talking about for a long time. Not only at the ICTR — we talked about it in gacaca, and everywhere else,” Cecile said.

By August, the issue had become a diplomatic incident. The Mechanism hadn’t notified the Rwandan government that it was meeting with witnesses inside the country, and the government was said to be furious. (The Mechanism declined to comment on the matter.) Its last meeting with the witnesses took place at the Rwandan Supreme Court, overseen by Rwanda’s top prosecutor.

“When we went to testify, no one told us, ‘You don't have the right to tell this story somewhere else.’”

The standoff also became a freedom of the press matter. The June court order prohibited anyone, not just the filmmaker, from “disseminating” information about the witnesses. Two weeks after the order, the Mechanism wrote to American journalists who had reviewed a rough cut of the film, asking them to “comply” with the order.

It's impossible to say exactly why the Mechanism tried to gag the film; it classified the matter as confidential, citing witness protection. Its spokesperson declined to answer questions about the case against Mitchell, citing confidentiality. Mitchell still has no idea why, precisely, the case was opened at all: She said the Mechanism refused requests by her lawyers to share relevant information from its investigation of her — citing, of course, confidentiality.

It’s also impossible to ask Judge Akay, who initiated the court proceedings against the film. Shortly after his injunction, Akay left Arusha, according to UN security personnel at the MICT offices there.

Then things then took an unexpected turn: In September, Akay was jailed as an alleged sympathizer of Fethullah Gülen, widely thought to be behind a coup attempt in Istanbul in July. Turkey’s president has since arrested at least 37,000 people and pushed another 100,000 out of their jobs. Akay remains in prison, although the Mechanism, at the request of the UN secretary-general, is publicly pushing Turkey to recognize Akay’s diplomatic immunity, citing his ongoing work for the court, and to release him; Turkey has refused.

But watching the film suggests the Mechanism may have had another interest in curtailing Mitchell. The ICTR was often criticized for being slow and expensive: Over 20 years, the court tried fewer than 100 cases and spent roughly $2 billion. The Akayesu verdict was universally regarded as one — of few, critics might say — inarguable achievements of the court.

Mitchell's film complicates that triumphant narrative by showing that the conviction was actually an accident of history: A single witness who happened to mention a new detail during the trial sent prosecutors back to a buried memo, and back to their own witnesses, to discover that there was compelling evidence linking Akayesu to sexual violence after all. The film presents a historic — but less heroic — version of events.

Whatever the motive, the Mechanism set out this summer to stop the film — and to do so by stopping the women who changed the course of history from willingly speaking out. It pursued Mitchell right up until the last minute: It was only 48 hours before the film officially debuted at the United Nations — with Seraphine, Victoire, and Cecile, in matching imishanana gowns and pearls, as guests of honor in a regal UN chamber — that the Mechanism dropped the injunction against the film and the investigation of the filmmaker.

That seemed to end the matter. But on Nov. 25, the Mechanism quietly dropped witness protection measures for the three women.

Njikam said it’s not unusual for the court to drop protection measures for a witness whose identity has been exposed, although several experts dispute this. One is Barbara Mulvaney, a prosecutor at the ICTR from 2002 to 2008, who dealt with dozens of witnesses in protection. “I’ve actually never heard of a motion like this, where they formally revoked or terminated a protective order,” she said.

Njikam said in this case, there was no more anonymity to protect. “It is the witnesses themselves who made their identities known to the public,” he said. “As far as the court is aware, there hasn’t been any physical threat to their life.”

But according to the court order, the witnesses haven’t been contacted by the Mechanism since the film was officially released, in October. By Njikam’s admission, it hasn’t even informed them that it suspended their witness protection more than three weeks ago. “[Informing them] is ongoing as we speak,” he said on Dec. 15. “I am unable to tell you now whether it’s been done.”

This is the very “choice” that so angered the women last May, when they were asked to sign a document in English, a language they can’t read, choosing between staying in the film and staying in witness protection.

“It's like we'd gone into a trap,” Seraphine said of dealing with the Mechanism. “When we went to testify, no one told us, 'This is where it ends from. You don't have the right to tell this story somewhere else.’”

Cecile, Victoire, and Seraphine share one certainty: Telling their stories, and reliving that trauma, was worth it because they won the case. “If we could have lost, it would have felt like a story for nothing,” Seraphine said.

They're proud and comforted to know that the Akayesu verdict is studied in virtually every human rights law class in the world, and that women in Congo and South Sudan and Burundi and beyond might feel brave enough to tell their own stories too, because the Akayesu verdict proves that individual voices can also be evidence, that rape is not just a personal trauma but an international crime, that genocide was and is real.

But not all witnesses’ days in court have been as vindicating. At the tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, 78 defendants have faced sexual violence charges, but only 32 have been convicted. At the International Criminal Court, a permanent war crimes body with near-global jurisdiction, has tried five cases that include sexual violence charges since opening in 2002 — and only earlier this year won its first conviction of sexual violence charges.

Winning isn't always enough. In 2005, nearly 10 years after the Akayesu verdict, Judge Pillay wrote in the foreword to a book about women's experiences in war: “I have now learned that Witness JJ [is] living in conditions far worse than that of the other survivors — a ramshackle hut on bare ground amidst sparse provisions, rejected by and rejecting the society of others ... The international community has responded to only one aspect of the aftermath of the genocide: that of bringing perpetrators to justice,” she wrote, and not the “needs of women to help feed, clothe, house, educate, heal and rebuild.”

Today, it’s another 10 years later, and JJ still doesn't have electricity. Hers is the only home I am not invited to visit, even when I ask — an aberration in a country where making a visit to someone's home is seen as a symbol of appreciation — and my interpreter agrees this is a sign she's probably not much better off today than when Pillay wrote about her. She has no job and virtually no income, and she lives alone, a circumstance that evokes pity in her cultural community.

“When they were raping us, at the same time they would beat us with the machete, with the wide part of the blade,” she explained. “I used to farm, but now, because I'm wounded, I can't hoe. If I try to be normal like others and go to the farm, I feel like my back is falling apart, and everything inside me is going to fall out. If I try for two days, I sleep for a month.” Even fetching water is an ordeal, because the well is far. “I can't even go with my small jerry can,” she said. “There's no life. I live like I'm not living.”

Victoire said she most wants — needs — something to do. “Even if it's like selling things, beans, rice, potatoes, getting them from somewhere and selling them again. Then I can get money to pay someone to dig for me. I could be independent.” If it sounds modest, that's exactly the point: “You start with small things and then it becomes bigger.”

That's what the other two women witnesses do. Seraphine hustles and hawks — “I'm a multitasker,” she said — and Cecile stitches. When they're able, that is. Sometimes, still, the trauma comes back, and the headaches are too much. But Seraphine insists she's a happy woman, known by everyone for her smile, and Cecile said she's universally regarded as the best neighbor where she lives.

Things seem harder for Victoire. The first day we talked, she cautioned against too much triumphalism. It's common, it seems, for people to cast the three women as heroes.

“Don't think it's only the three of us. It was many of us who told our stories, but some died on the way. They had different diseases they got from the rapes, and so many of them died before even seeing what we achieved. You're only seeing us who are still alive,” she said. “I think for all the women who've been through that — we're all dead women standing. It's because we have dignity that we stand up for ourselves, but it's not easy.”

Seraphine said that testifying made coping easier. “It's something that built us,” she said, tears hovering. “Before, we were really hopeless. We didn't think anyone would even want to fight for our rights or bring us justice.”

And Victoire acknowledged that, with time, things get clearer, even if she doesn’t feel that they’re much easier.

“Slowly, we've learned to live with ourselves. We got to the point that we testified at our village, in our commune. Many of those that did that to us, who raped us, they fled. Some we know; others we don't know. The ones who fled, we don't know where they are, but they know us. It's only the will of God that we're still around,” Victoire said. “So we're careful. But we've learned to move on and live with who we became.”