In California, April really is the cruelest month.

At a time when the Golden State's reservoirs should be brimming and the snowpack deep, much of California is instead parched and dry. Gov. Jerry Brown has announced historic mandatory water restrictions on urban areas, and some are wondering if people and business are about to start fleeing.

But understanding the true severity of California's drought is harder to pin down and depends a lot on how it's defined, according to scientists who spoke with BuzzFeed News. To understand what's going on it's easiest to break the drought down into two very general categories: First, how much water California has in an absolute sense, and second, how much California needs for all of its people.

California has very little water right now.

You may have heard that the current drought is California's worst in 1,200 years. That oft-cited figure comes from a paper by Daniel Griffin, of the University of Minnesota, and Kevin Anchukaitis, of the Woods Hole Oceanic Institution.

In conversations with BuzzFeed News, both researchers explained that they came to that conclusion after studying tree ring samples, as well as using what's known as the Palmer Drought Severity Index, or PDSI. Basically the PDSI measures soil moisture as it compares to what is "normal" for a particular place.

What Anchukaitis and Griffin ultimately found is that the soil moisture in central and southern California has fallen to its lowest level for any three year period on record. Other droughts may have been longer or drier, but they were punctuated by rainy years.

But that isn't the end of the story. Griffin and Anchukaitis were looking only at one type of data, and both said there are other ways to evaluate the drought.

"There's no one definition of drought," Anchukaitis explained.

By other more narrow measures, the current drought looks more complicated — and in some cases not quite so bad.

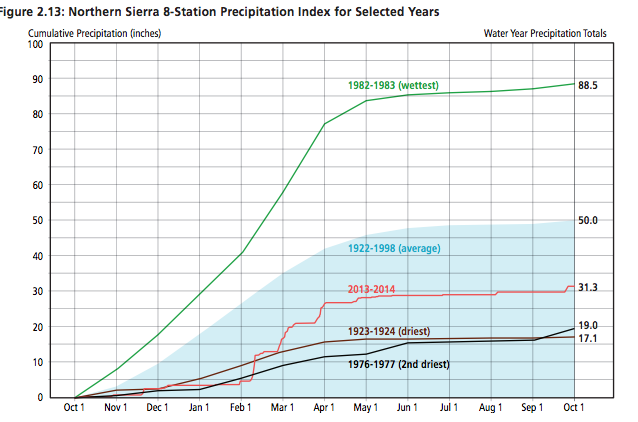

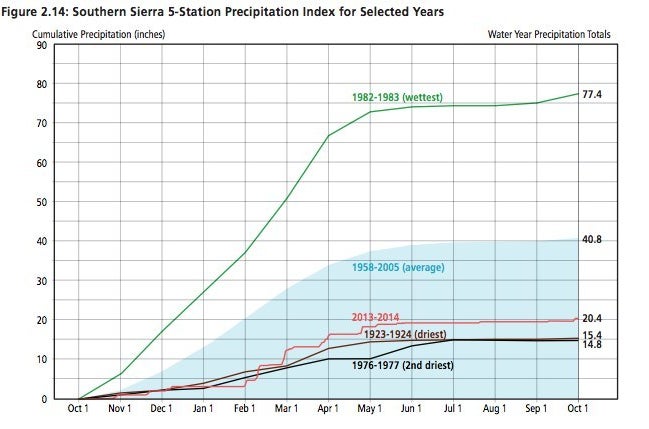

A recent report from the California Department of Water Resources called the last three years the driest "in terms of statewide precipitation."

But the report goes on to note that there were other, shorter periods during the 1970s and the 1920s when California received even less rain.

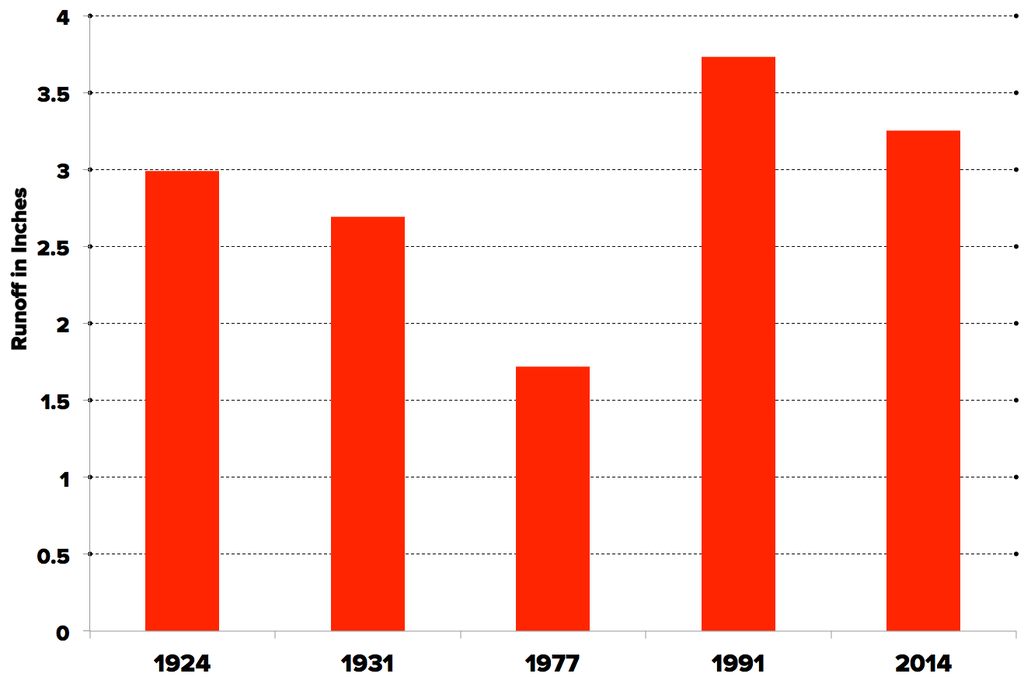

Runoff during the current drought has been terrible, but not the worst.

After it rains or snows, some water evaporates, some absorbs into the ground, and some is soaked up by plants. Whatever remains flows into streams and rivers — and in some cases eventually down to people — and is called runoff.

The graph above compares average statewide water runoff for California's five worst years since 1901. During that period, 1977 was by far the worst, with a mere 1.72 inches of runoff. By comparison, the best year, 1983, had 22.7 inches of runoff.

It's worth noting that 2012 and 2013 — the first years of the current drought — rank as having the 26th and 19th least amount of runoff, respectively.

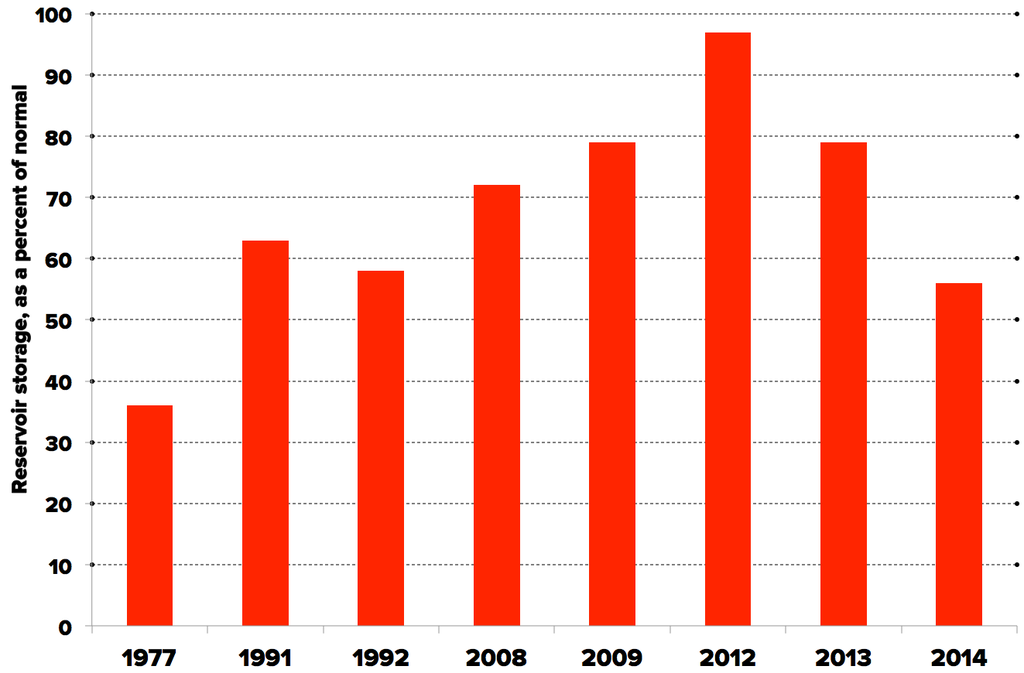

California's reservoir levels have fallen during the current drought, but are not at historic lows.

As of April 14, Lake Oroville is at 65% of its historical average level, according to DWR data. Lake Shasta is at 72% of average. Other reservoirs in the state range from 85% of historic capacity to 16%.

California also had "mega-droughts" during the medieval period that lasted far longer than the current drought.

The New York Times recently reported on a pair of mega-droughts that gripped the region after the year 800 and, collectively, lasted until around 1300.

Griffin told BuzzFeed News that he and Anchukaitis saw evidence of mega-droughts in their study of California's tree rings. What made those droughts different, however, was that like other more recent dry periods, they were broken up by rainy years.

"In a way it kind of matters how you define drought," he added.

Another way to look at droughts in the distant past is to look at their local impacts. The DWR reports, for example, that in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers — which now supply much of the state's water supply — 1580 was the driest year. At that time, only about half as much water was flowing as in 1924, the driest year since modern record keeping began.

There was also a drought in the 1860s that was so severe it killed off California's cattle rancho system because there was no grass for livestock to eat, according to DWR.

The loss of cattle was fearful. The plains were strewn with their carcasses. In marshy places and around the cienegas, where there was a vestige of green, the ground was covered with their skeletons, and the traveler for years afterward was often startled by coming suddenly on a veritable Golgotha – a place of skulls – the long horns standing out in defiant attitude, as if protecting the fleshless bones.

In another case, during a drought in the late 1920s, the water in Lake Tahoe got so low that scientists discovered tree stumps normally submerged in water and realized there had been previous very dry periods.

These examples are very specific and tied to certain locations, effects, or conditions, but show that extreme drought conditions are not new in California.

So what are the factors making this drought so severe? For one thing, the heat.

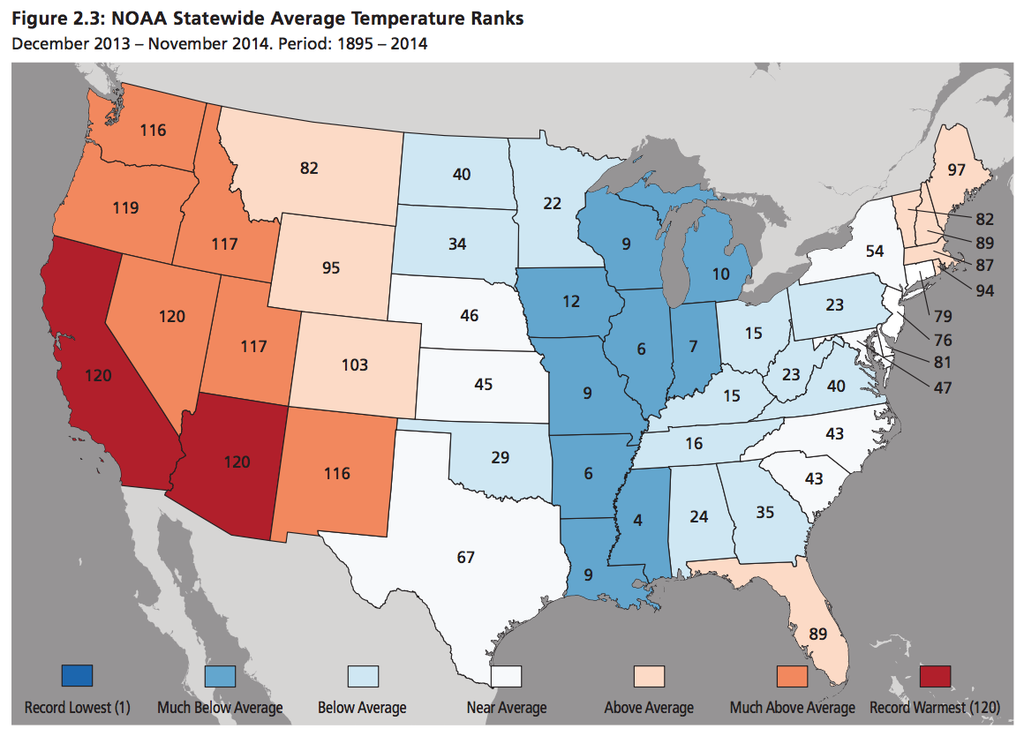

Last year, California experienced its warmest year on record since the 19th century, and government agencies also determined that 2014 was Earth's overall warmest year since 1880.

Moreover, the decade between 2001 and 2010 was the warmest since the turn of the 20th Century, according to DWR. The period since 1950 has been the warmest in the last 600 years.

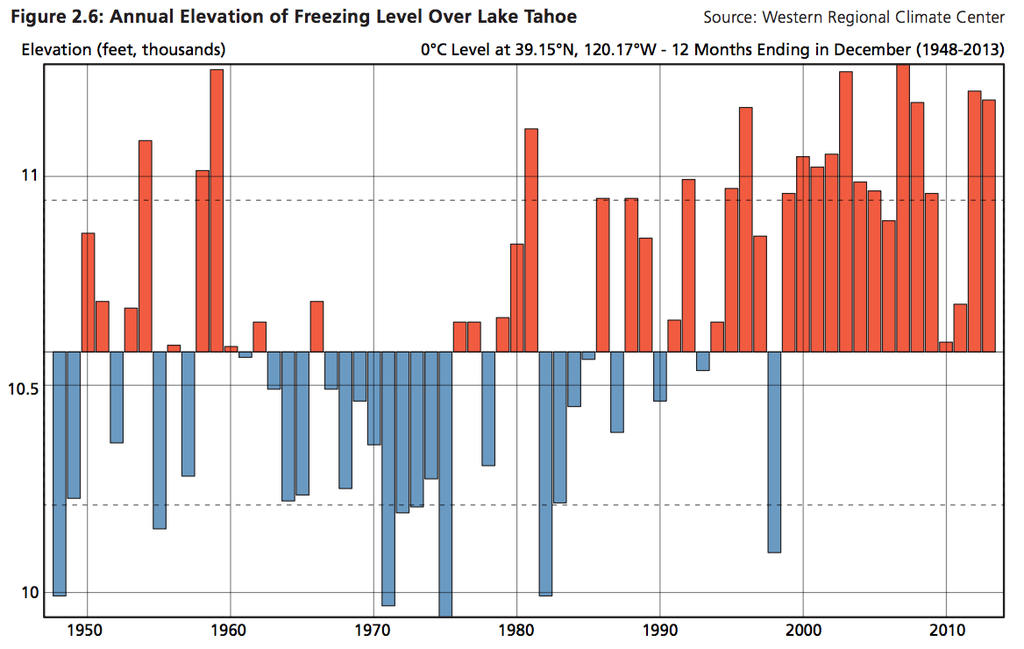

The warmer temperatures make the drought worse by pushing the elevation at which water freezes higher and higher into the mountains. As that happens, more water falls as rain than snow, meaning less water gets stored on mountain slopes for future use.

The combination of very little precipitation and warm temperatures has led to a reduced snowpack.

Snowpack may be the most apocalyptic data point in the current drought. It made headlines April 1 when Gov. Brown announced mandatory water restrictions from a grassy meadow that should have been covered in snow. At the time, California's snowpack was only 5% of normal.

A storm subsequently bumped those numbers back up as high as 8%, but they later fell even further to 4% of normal.

Another problem with heat is that it means more water loss to evaporation and vegetation.

In addition to the current drought severity, the state's rising population requires more of an ever-dwindling water supply.

While scientists will debate the severity of hydrologic or meteorological droughts, one one of the most basic ways to define a drought is by how it affects people.

"In the purest sense, drought might be kind of a social construct, if we have less moisture than we need," Griffin said.

And there's a lot more people in California than there used to be. In 1930, the entire population of California was 5.6 million, or just slightly more than the current populations of Los Angeles and San Diego. Today, the state's population is more than 38 million, which is more than New York and Pennsylvania combined.

Peter Gleick, a climate scientist and president of the Pacific Institute, called the current situation a "supply drought and a demand drought" because there is both very little water and great need. He contrasted today's conditions with past droughts of the Dust Bowl era, which he characterized as stemming more singularly from supply issues. Gleick also pointed out there are much drier places than California, but if they have small or no populations, droughts don't have much impact.

"The simplest way to think about a drought is the difference between how much water we have and how much water we want," Gleick told BuzzFeed News. "In California right now there is a gross miss match between supply and demand."

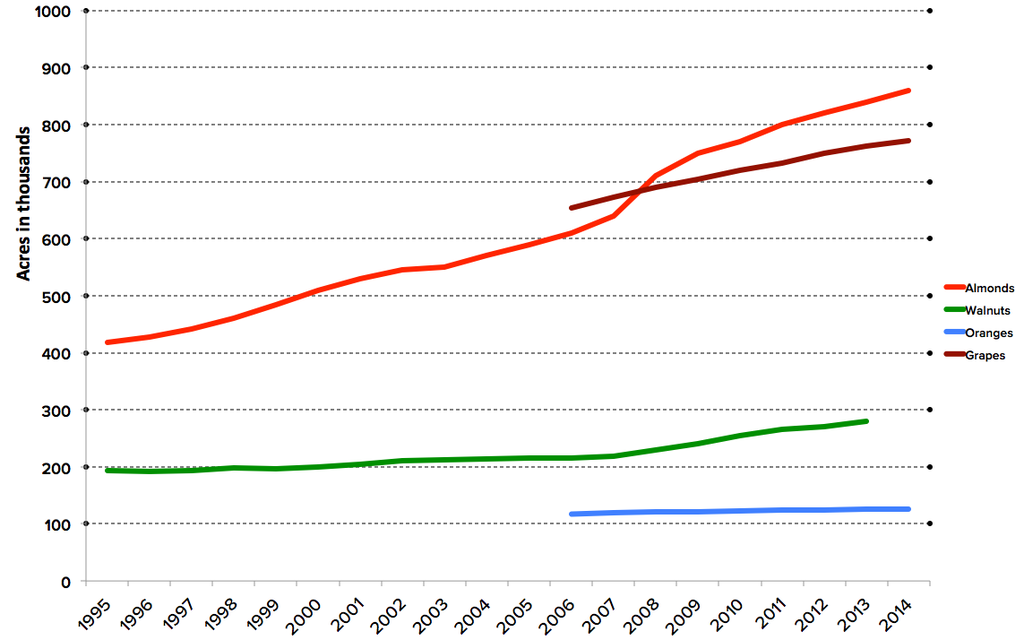

In addition to population growth, California also has far more farmland than it did in the past.

In 1929, California had 6.5 million acres devoted to growing and harvesting crops. By 2010, the state had 31.5 million acres of agricultural land.

In some cases, California has seen an uptick in agricultural production even in recent years.

Environmental factors such as heat also exacerbate supply and demand problems by driving up the water requirements for crops.

The role and responsibility of farmers in reducing water consumption is a contentious topic in California, and it's clear that there is more farmland in California today than there was 100 years ago. And that means more demand.

Gleick pointed out that farmers have already experienced significant cuts in the amount of water they can access and cautioned against intense focus on a single crop such as almonds — which have garnered significant media attention this year. Still, he said that in general California needs to have a stronger sense of urgency when it comes to managing water use.

"The fact that we still have lawns means we're still not taking this seriously," he said. "The fact that we're not having a lively debate about what crops we're growing and what irrigation techniques we're using means were not taking this seriously."

In this context, it's easy to see Gov. Brown's mandatory water restrictions, which are still being developed, as an attempt to deal with the drought by reducing demand. And emergency declarations — which have been more widespread during this drought — are a way for communities to access resources that will help them cope with supply shortfalls.

So is this drought really the worst?

The exact severity of California's situation ultimately depends on how you slice it. Precipitation, soil moisture, runoff, reservoir levels, and other metrics all offer different views of the drought, and many of them are quite gloomy.

"By all integrated measures," Gleick said, "this is the worst drought on record."

What's clear, though, is that the real struggle for California's water is now just beginning, as cities struggle with making major cuts. Some of those communities in particular are not pleased about what they're being asked to cut, and in parts of the state significant shortfalls are only now trickling down to cities.

The scientists who spoke with BuzzFeed News also said that California, and the West in general, may face longer, drier periods going forward as the climate changes. And that, they argued, means people are going to have to seriously grapple with ways to cut back on how much water they use.

"I think we're moving in the right direction," Gleick said, "but not quickly enough."