The giant El Niño that fueled flooding rains in Texas this year but failed to make a big dent in California's extreme drought, was declared dead Thursday, opening the door to a La Niña and extended period of dryness in the West.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced the latest El Niño event had come to an end, saying "we're sticking a fork in this El Niño and calling it done." According to NOAA forecasters, the unusually warm pool of water in the equatorial Pacific Ocean had "mostly returned to normal by the end of May."

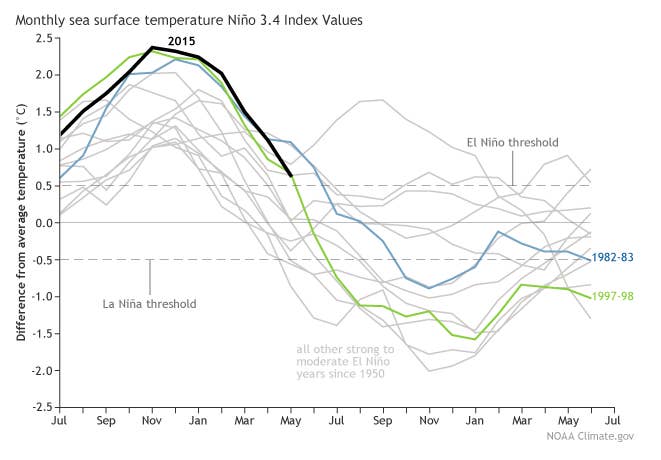

The El Niño was born in 2014, NASA climatologist Bill Patzert told BuzzFeed News. Patzert, who coined the nickname "Godzilla El Niño," said it "came early, it was immense, and it was quite long lasting."

Droughts in India and Africa, recent flooding in Texas, and an earlier-than-usual tornado season in the Plains states were among the significant effects of the El Niño, he said.

The warming of the Pacific also contributed to massive coral bleaching events, NOAA coral reef watch coordinator Mark Eakin told the Associated Press.

The question now is if sea surface temperatures will swing back in the other direction and become cooler than normal, leading to a La Niña. According to NOAA, there is now a 65% chance of a La Niña by July, and a 75% chance by the fall.

Patzert agreed that a La Niña event was likely, but with warm water still lingering in the Pacific, suggested it was still too early to be certain what would happen.

"At this point this El Niño is leaving us reluctantly," he said. "Our future is a little up in the air here."

Data from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory bears out how up in the air the next few months actually are; though water temperatures in the equatorial Pacific have indeed dropped, a large mass of warm water remains. That's in contrast to the last major El Niño in the 1990s, represented on the left, when the warm water had all but dissipated by spring of 1998.

During a La Niña year, the southern tier of the U.S. tends to be cooler and drier, while the north is wetter and stormier. That's in contrast to El Niño years, when the Southwest and California tend to receive more precipitation that usual.

A drier year would be bad news for much of the West, which Patzert said has been grappling with a drought that effectively began after the last big El Niño in the late 1990s.

"The real story is the Godzilla drought, not the Godzilla El Niño," Patzert said, pointing to record low levels in Nevada's Lake Mead as an example.

California is now in its fifth consecutive drought year, and according to the U.S. Drought Monitor more than 95% of the state is currently experiencing some level of abnormal dryness or drought.

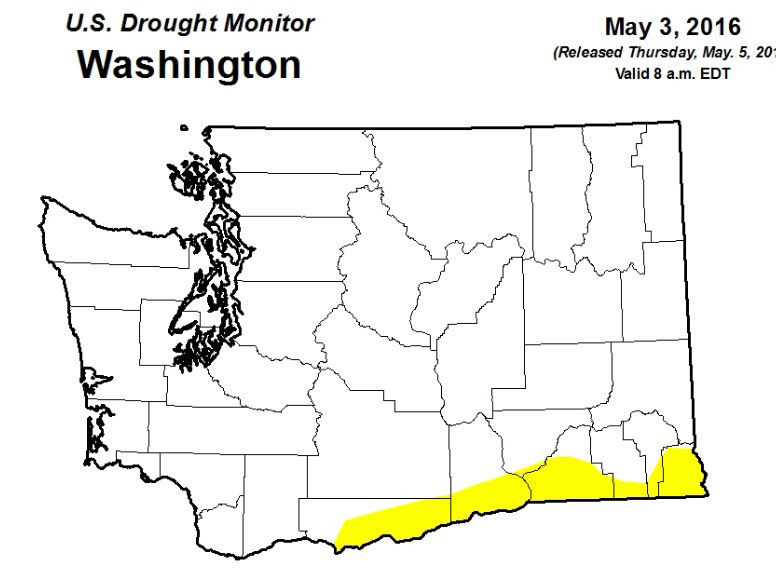

Abnormal dryness also affects nearly 60% of the West, as comprised by the 11 contiguous western states. States such as Oregon and Washington are beginning to experiencing large increases in dryness as summer begins.

But La Niña or not, the West — and California in particular — could be in for hard times. Many in the region had hoped that a powerful El Niño in 2015 and 2016 would end, or at least, put a major dent in the drought. And while the past six months have been wetter than the same period in 2014 and 2015, snowpack levels are still far below normal and the latest drought numbers show conditions once again getting worse.

"We are in a drought forever," Patzert said. "I can't think of any scenario where we would have six wet El Niño years in a row, which would top out all the reservoirs and the ground water supply."