One hundred miles northwest of the Four Corners, two buttes rise out of the red dirt and scrubby brush. The buttes, named for their ursine appearance, are known as Bears Ears, but for visitors of this remote corner of Utah, the glowing sandstone and hawks gliding overhead might distract from what the area is becoming: a battleground.

This sprawling 1.9 million-acre parcel of land may soon become a new national monument — a protected space similar to a national park. There are a few ways for a place to obtain that status, but in the case of Bears Ears, all eyes are currently trained on President Obama, who can declare a national monument with the wave of his pen.

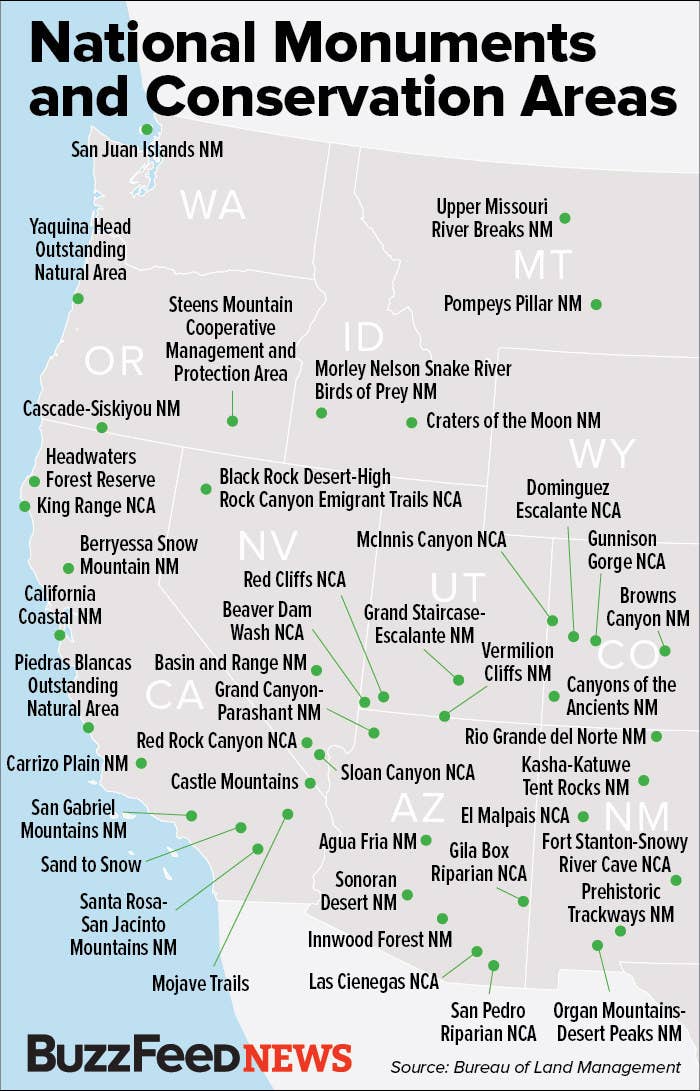

The president just created three new national monuments in California. Together with existing conservation areas in the region, the national monuments create the second largest desert preserve in the world. Last year, the president created a 704,000-acre national monument called Basin and Range in Nevada, as well as others in California and Texas. In 2013, Obama designated a handful of new monuments, including several in western states.

In each of these cases, Obama cited the Antiquities Act, a relatively obscure law dating back to 1906 that's designed to protect things like archeological sites. The law gives a president wide-ranging discretion to set aside public lands, and it has been used by chief executives of both political parties. Bill Clinton, for example, famously and controversially used to it create the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. George W. Bush used the law to set aside the vast Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii.

But Obama has been more aggressive; according to the White House, the president "has protected more acres of public lands and water than any administration in American history."

Advocates of conserving these spaces often see a presidential proclamation as an advantage, a way to bypass the byzantine process that usually comes with getting things done in government.

But critics say these kind of proclamations subvert the democratic process and undermine local interests.

Battles over the federal government's ownership of large stretches of land in the West go way back. The 1970s and 80s saw the rise of the "Sagebrush Rebellion," and the Bundy-led standoffs in Nevada and Oregon were the latest iteration of that still-simmering conflict. Across the West people are still arguing, and occasionally fighting, over who should control the land.

And there's no place where that's more true than Bears Ears. A coalition of Native Americans wants the large stretch of land to become a national monument — but a special kind where they share control.

"It’s more than simply saying that it's an important piece of land"

The push to turn Bears Ears into a national monument took off last fall. Though there had been talk of protecting the site before, a group of Native American tribes calling themselves the Bears Ears Coalition submitted a 66-page proposal for the site in October.

The group says the site is peppered with more than 100,000 Native American sites, some of which date back hundreds and thousands of years, and "we have been here the longest."

"Our ancestors variously inhabited, crossed, hunted, gathered, prayed, and built civilizations on these lands," it says. "Their presence is manifested in migration routes, ancient roads, great houses, villages, granaries, hogans, wikiups, sweat lodges, corrals, petroglyphs and pictographs, tipi rings, and shade houses."

Eric Descheenie, a coalition co-chair and senior advisor to the president of the Navajo Nation, said that Native Americans in the region see the land as something more than just a place of biological and geological interest. It's a sacred space, he said, that has "personhood and agency" and where ceremonies have "been practiced verbatim since time immemorial."

"It’s more than simply saying that it's an important piece of land, it actually harbors our ability to heal," Descheenie added.

The proposal asks Obama to set aside 1.9 million acres. And with Obama's time in office winding down, along with his interest in monument designation, the coalition is optimistic it'll score a victory.

"Right now the tribes are incredibly hopeful," Descheenie said.

But given the contentious mood surrounding federal lands in the West, the nature of the coalition's proposal is significant.

According to Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, a Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council Member who has worked with the coalition, the tribes are asking not for a traditional declaration, but instead for one that would have them co-managing the site with the feds. It's a novel, and never-before-deployed idea.

"We want to be a part of the solution."

"It's a means of us extending our hands out in partnership rather than asking for a handout," she explained. "We want to be a part of the solution."

Descheenie said this process is an essential part of the coalition's proposal, and would allow the site to evolve according to need. When asked if an ordinary proclamation and monument — in which the federal government retains full control of the site — would be problematic, Descheenie said he believed it would.

"I know it would be a problem," he added.

In other words, the coalition wants an Antiquities Act declaration, but appears reluctant to accept the kind of unilateral authority the typically characterizes national monuments.

But some locals and Utah lawmakers adamantly oppose turning Bears Ears into a national monument at all, and want the federal government completely out of the state.

After the Bears Ears Coalition finished it's proposal last fall, it took it to Utah Representatives Rob Bishop and Jason Chaffetz — Republicans who have been vocal critics of federal land use.

Neither Bishop nor Chaffetz responded to BuzzFeed News' request for comment, but both Descheenie and Lopez-Whiteskunk said reaching out to the lawmakers did not end well.

"There was no substantive engaged," Descheenie said. "They nodded along, they smiled and they were cordial, and at the end of the day that was about it. It was kind of like talking to a wall that just wouldn’t respond."

That may be because the lawmakers have created their own proposal for Utah's public lands.

The Utah Public Lands initiative would set aside some lands for conservation, and is billed as being based on the "belief that conservation and economic development can coexist and make Utah a better place to live, work, and visit." Still, it has been blasted by conservationists and the Bears Ears Coalition, which called it "woefully inadequate."

The public lands initiative is not limited to Bears Ears, but Chaffetz, Bishop, and all of Utah's U.S. representatives and senators sent a letter to Obama in January specifically opposing a national monument. The letter warned of "fierce local opposition" should the president move forward with a "veiled and unilateral" proclamation and argued that decisions should be made "with community involvement and local support."

"We believe the wisest land-use decisions are made with community involvement and local support," it added.

The initiative and accompanying resistance to a national monument spring from widespread angst, and anxiety, in the rural West over the way federal agencies manage land. Those feelings are particularly strong in Utah's San Juan County, the location of Bears Ears and where, according to County Commissioner Phil Lyman, only 8% of the land is privately owned.

Lyman told BuzzFeed News federal policies have slowly chipped away at the economy of his county and "for the most part people don't appreciate a unilateral executive order and I would certainly say that's the case with Bears Ears National Monument."

Many in the area are concerned a decision by Obama would restrict mining and grazing on the land. "If you're relying on those for any part of your economy," Lyman said, "you're just up a creek without a paddle."

Bruce Adams, also a commissioner in San Juan County, agreed with Lyman on the issue.

"For them to create a national monument feels like they're pulling the rug out from under us," Adams said. Both commissioners said some Native Americans in the region also share their concerns.

Sen. Mike Lee — who also opposes a presidential designation of a national monument — has pointed to the Kaayelii band of the Navajo, saying they believe it "would threaten their livelihood and destroy their way of life."

A representative of the Kaayelii did not respond to a BuzzFeed News request for comment.

Conn Carroll, a spokesman for Lee, told BuzzFeed News that when the federal government sets aside land it "puts a monkey wrench in the economic development of these rural counties." Carroll acknowledged that there are differing views on what should happen to Bears Ears, but argued everyone should have some say in what happens, not just the White House.

"The question is, how are we going to decide that?" Carroll added. "Is it going to be done in a democratic way?"

Obama has not said what plans, if any, he has for Bears Ears, and White House officials did not respond to a request for comment. But in the meantime, there is a long list of other potential places in the West that could also become national monuments, and points of conflict.

Observers have pointed to other areas in Utah, as well as New Mexico, Montana, and Idaho. In Nevada, there is a push to designate Gold Butte a national monument.

Located near the Arizona border, Gold Butte is filled with unique geological features and ancient petroglyphs, Annette Magnus, executive director of Battle Born Progress, an advocacy group that has pushed for a monument, told BuzzFeed News.

"It desperately needs to be preserved," she said.

Gold Butte is significant because its part of the region contested during the first Bundy standoff in 2014, when family patriarch Cliven Bundy faced off with federal authorities in southern Nevada over cattle grazing rights.

Following the standoff, the federal government pulled out of the Gold Butte area. There were later reports of shots fired at a survey team, prompting the Bureau of Land Management to warn its staff to stay away from the region.

The area remained hotly contested and largely unmanaged into this year, and the conflicts show how federal land generally, and candidates for monumentalization specifically, remain flash points.

Magnus — who said she had seen cows grazing the range during her visits to the area — pointed to the Bundys as one reason the area needs to be turned into a national monument. But she also explained that in Nevada there are two ways for that to happen: by legislation and presidential proclamation. Advocates for a monument will take either, Magnus said, adding that the legislative option has the benefit of consensus.

"We’d love to have everyone on board," she said.