There are plenty of things to dislike about Michael Bloomberg's presidential campaign, and most of them got a vigorous hearing during the last couple of Democratic debates: the way he’s seeking to win the nomination through the sheer force of money alone, or the racist injustice of his signature "stop and frisk" policy while he was mayor of New York City.

But there’s another aspect to his campaign that deserves more scorn, if we’re ever to take him seriously at all: the truly pathetic lack of vision and ambition on display from someone who should be most familiar with the importance of both.

If you pay attention to what he’s actually saying in his stump speeches and his firehose of TV commercials, as I unfortunately have been recently, what jumps out is the lack of any idea big enough to match the moment we're living in. His ads, more than half a billion dollars’ worth so far, are banal and generic. There’s nothing there.

A snippet from one of his early ads: "He could’ve just been the middle-class kid who made good, but Mike Bloomberg became the guy who did good." Another included a gem about Mike’s desire to “restore faith in the dream that defines us,” where “the wealthy will pay more in taxes and the middle-class get their fair share.”

We’re not in the presence of a maestro here.

Consider his promise to untangle the health care morass with a solution only a next-level thinker could come up with: “Everyone without health insurance can get it, and everyone who likes theirs, keep it.”

Now compare Bloomberg’s TV spot to Lyndon Johnson when he launched his War on Poverty. “Our aim is not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it," Johnson said. Sure, it was just a line in a speech. But the war on poverty included the passage of Medicare, which changed our country for good and ultimately gave tens of millions of seniors a lifeline.

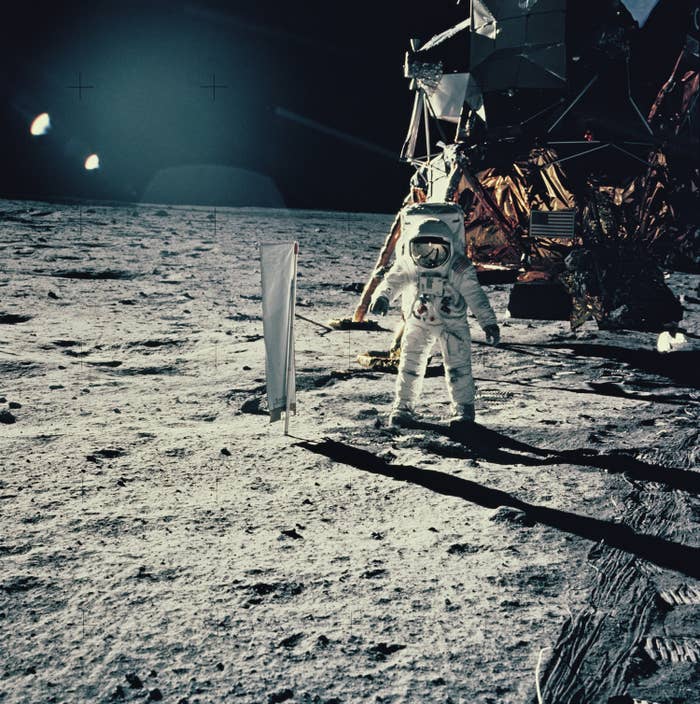

John F. Kennedy knew how important the space race was in 1961 when he asked Congress for a trainload full of money to get to the moon "before this decade is out," which we did. He framed it as a way to checkmate the Russians militarily. Dwight Eisenhower got Congress to increase gasoline taxes (try to imagine that now) to start construction on the interstate highway system, which he sold, in part, as a national defense project. It changed the country and the electoral map forever, and the Transcontinental Railroad finally connected the nation from coast to coast.

Michael Bloomberg has shown no sign he believes we can do big things again. Perhaps his most ambitious plan is simply managing to win an election. “Defeating Donald Trump — and rebuilding America — is the most urgent and important fight of our lives,” he’s said.

He is counting on his lack of vision to carry the day, with the help of as much of his fortune he can spend. Ross Perot thought his wealth would give him an upset in 1992 when he ran against Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush — his favorite talking points were about "looking under the hood" of a car and fixing everything, including — drumroll — “waste in government.” He received 19% of the vote and soon disappeared from the national stage.

There’s nothing new to this Bloombergian smallness of vision. Last year, when asked about the Green New Deal that is supported by so many leading progressives, Bloomberg said he was “a little bit tired of listening to things that are pie in the sky, that are never going to pass, and we’re never going to afford."

“I think it’s just disingenuous to promote those things,” he said.

This brand of cynical, insidious advice to Americans — to stop dreaming big, to keep counting their pennies, and stay mired in a sense of hopelessness — has been rightly abandoned by the people currently leading the Democratic primary race. And a man who owes his fortune and political prominence to the greatness of New York City should know better.

The wonder that is New York exists thanks in large part to the kind of pie-in-the-sky projects — impossibly ambitious, realized despite the objections of naysayers and budget curmudgeons — that Bloomberg now dismisses. The state’s sixth governor, DeWitt Clinton, proposed building a canal that would run from the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. His opponents called it “Clinton’s Folly” and “Clinton’s Ditch,” and predicted all manner of doom. When the Erie Canal was completed in 1825, it made New York the economic powerhouse it still is today.

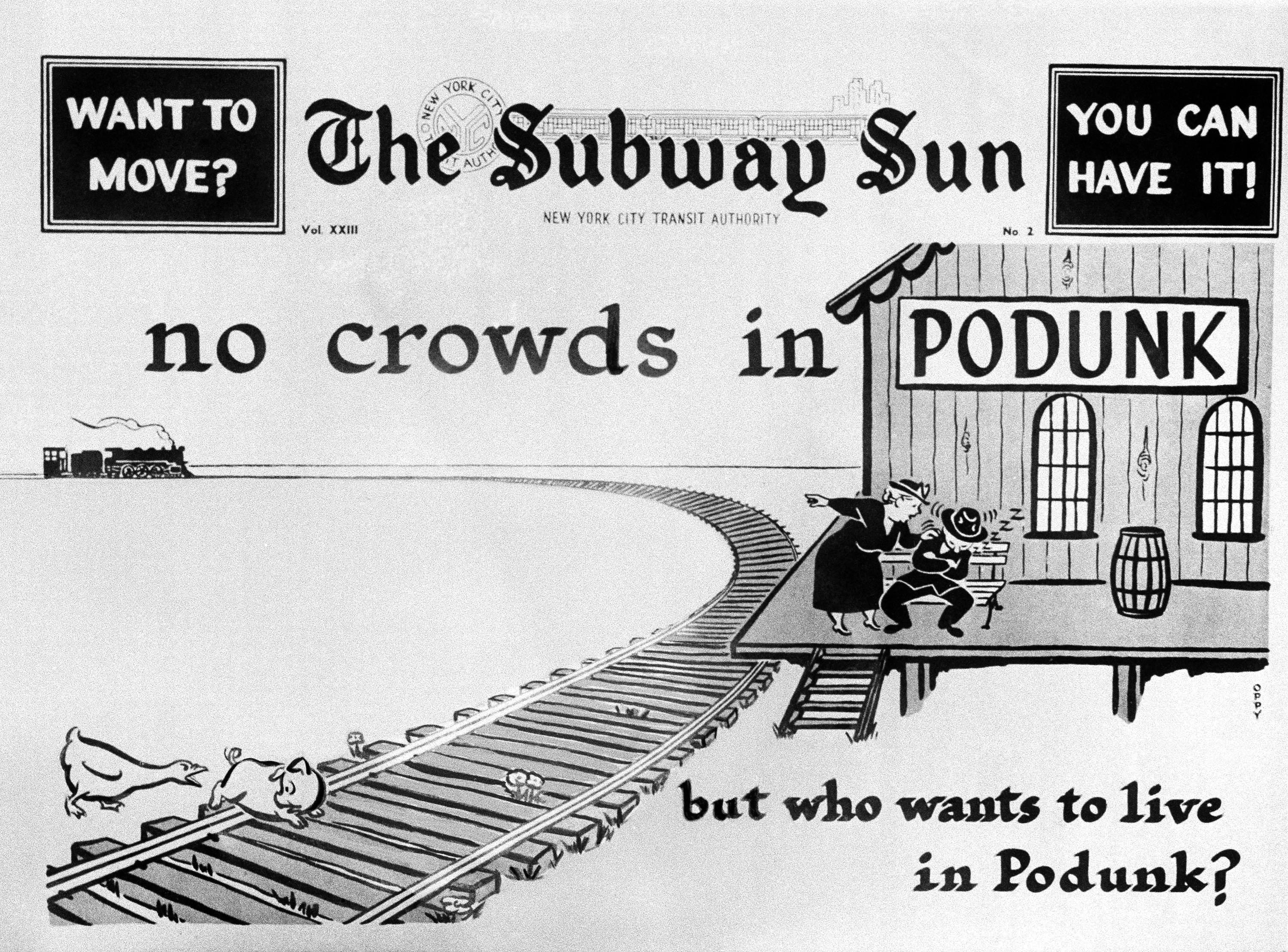

Bloomberg probably would have thought it was similarly unrealistic to propose building the New York City subway system, which carries 6 million people a day. Without it, the city would be a collection of small towns. One can only guess the contempt he’d have for an idea like the State University of New York, strung together by Nelson Rockefeller from a group of small community colleges and transformed into a system that still provides hundreds of thousands of students with an affordable, quality education every year.

In his biography of Nelson Rockefeller, Richard Norton Smith quotes him as saying “there is no problem that can’t be solved.” He never said “we can't afford it.” And there is no record of him bragging on a campaign platform about how rich he was (he really didn't want anyone to know).

Bloomberg’s approach comes from a less visionary tradition, which also has precedents in New York. Before there was President Trump, New York’s Democratic governor Hugh Carey, whose family was in the oil business, announced at his inauguration in 1975 that “the days of wine and roses are over” — an astonishing insult in a state that had elected Al Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the two creators of the New Deal, to the governorship.

Carey wasn’t kidding: Within a year, he and the Democratic mayor of New York, Abe Beame — whose parents were Socialists — ended free tuition at the City University of New York, which had been in effect since 1847.

Bill Clinton went a step further in 1993, proclaiming an end to the “era of big government.” It was the kind of language you expected to hear on Fox News, not from a Democratic president. The result is a country whose philosophy has changed from unbridled optimism to defeated penny-pinching — unless, of course, the vast public outlays are directed to big businesses and billion-dollar sports stadiums owned by billionaires.

When people like Michael Bloomberg say the Green New Deal is unrealistic, remember the half-trillion-dollar TARP program to bail out the financial sector. Just about anything can magically become realistic if it benefits the right people: the General Motors bailout, vast subsidies for giant agricultural corporations, or the zero dollars in real estate taxes paid by the Dolan family, owners of Madison Square Garden, and the $360 million tax break for Donald Trump's Grand Hyatt in New York.

Thankfully, an optimistic spirit is again rearing its head. You’re seeing it in the progressive grassroots, the high school activists — and in the Democratic presidential race, where big ideas for the future are once again in vogue.

Today it’s the people who reflexively say “this can’t be done” who we should be worried about. They’re the ones who’ve lost touch with the best traditions of our politics. You can hear their chorus of concerns every time these big ideas are floated: Medicare for All? Impossible. Free public college? Too expensive. Tax those who can afford it at a higher rate? Never. These people have given up — they should be benched, or sent back to the minor leagues.

Jim Callaghan has been writing about New York as a reporter, editor, columnist, and publisher since 1978.