It's mid-morning on a muggy Wednesday in August, and Melissa Rojas and I are careening east through Texas on Interstate 30. The sky is ominous and dark for miles, but we’re making good time, and we’re convinced we'll outrun any storm that’s brewing.

Just outside of Dallas, though, the heavens crack open and we slam into sheets of water. The road becomes a manic, gray blur. Red brake lights pop up ahead. A man’s voice yells over the CB radio: "Where the fuck did the road go?" Twenty yards up, a black sedan has spun out. Rojas, 34, slows our Freightliner Coronado to 55 miles per hour, then 35, then 15 as we glide around the accident.

Throughout this meteorological emergency, Rojas has kept her French-manicured hands resting calmly on the steering wheel. As we drive past the breakdown, she eases the 13-speed gearshift into sixth. "This is actually no more dangerous than being in a car," she says casually, reaching up to adjust her rearview mirror. "That car spun out ’cause it was really light.”

"But," she adds, turning her eyes back to the road, "if I hydroplane, we're flipping over."

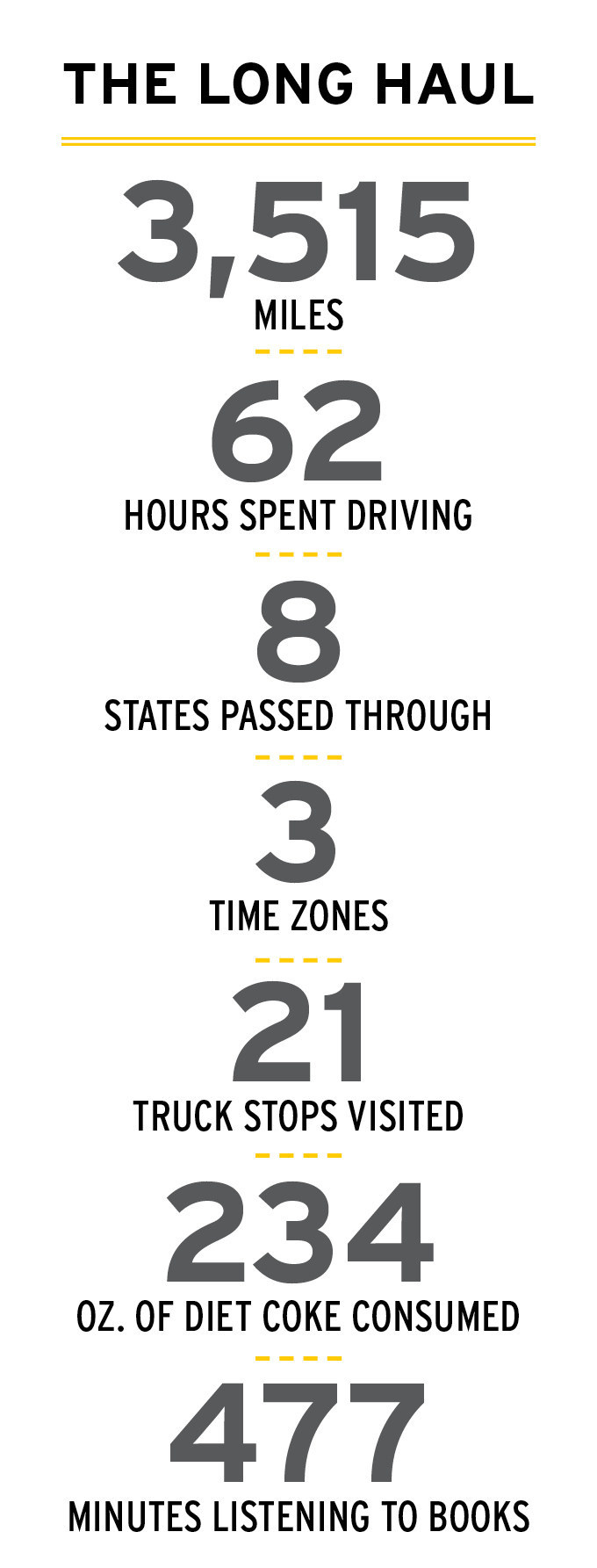

I'm trying not to panic, but I will later be told that my knuckles turned white during what seemed to be a close brush with death. But for Rojas, a third-generation truck driver, this moment could not be more ordinary. The Michigan-based mom has been behind the wheel of long-haul trucks for three and a half years and currently runs a route that takes her from Michigan to New Mexico and back again — a six-day, 3,500-mile round trip that she makes every single week.

By the time we hit the rain, we're five days in. We've dined in the truck, slept in the truck, and considered the possibility of urinating in the truck. We have answered to no one and, with the exception of getting the cargo at the right time, have made our own schedule, determined our own route, and stopped whenever nature called.

This isn’t to say that the open road is totally lawless. There are rules — regulations, even! — that govern the behavior of the men and women who commandeer 18-wheelers. But trucking is one of the last American industries in which those seeking to start over can create themselves anew on the country's highways. Training programs are open to anyone and everyone, and many see it as a path to salvation in exchange for little more than putting life, limb, and sanity on the line and staring down the very nothingness of the turnpike in the name of American commerce.

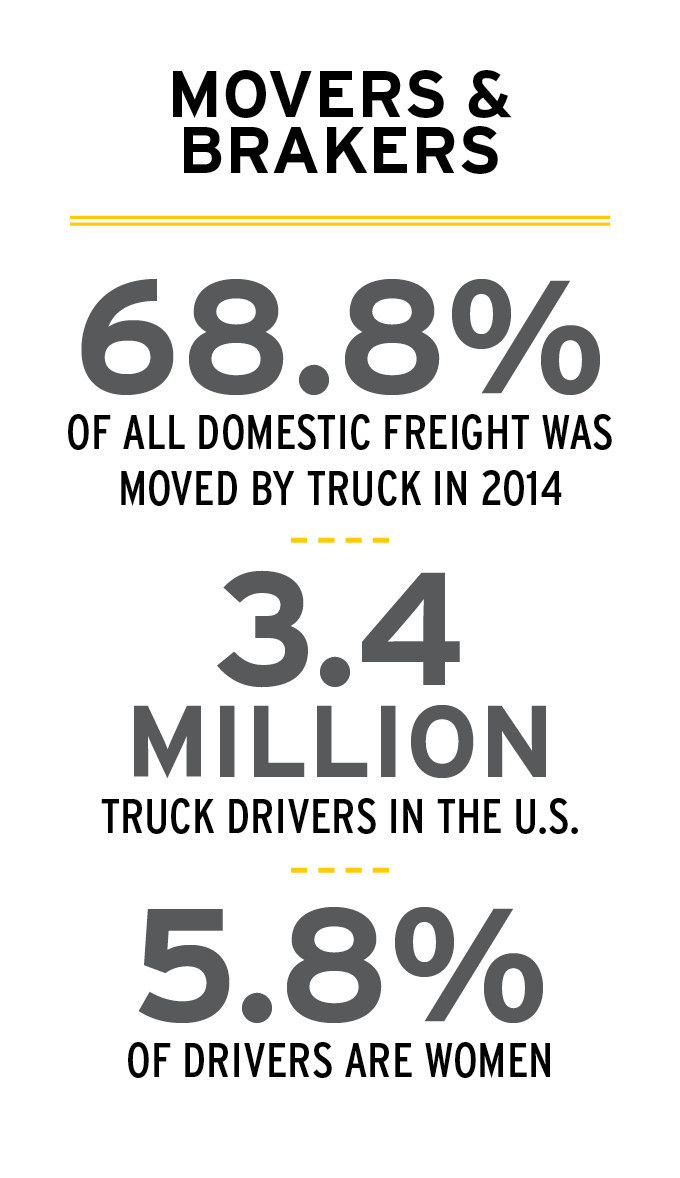

Melissa Rojas is one of very few women who do this job. In 2014, 3.4 million truck drivers were on the road, and only 5.8% of them were women. It's a dangerous job all around; in 2013, 3,858 drivers were involved in fatal accidents. There are also constant, unexpected hazards: One of Rojas's male friends would later tell me about encountering alligators at a loading dock lot in Louisiana bayou country. But for female drivers, the danger goes much further. Reports of rape and sexual harassment on the road are rampant, often at the hands of other drivers. And trucking is riddled with an outdated boys club mentality; last year, lawsuits were filed against at least two major trucking companies, claiming that female employees were routinely harassed or assaulted, and that supervisors did nothing about it.

Driving a truck keeps Rojas away from her children and puts aches and pains in her body. The road can be tiresome, and the hours of solitude sometimes become heartbreakingly lonely. But she's propelled by her desire to take care of her kids by any means necessary, and the job’s isolation is balanced by the constant promise of freedom over the horizon.

“What other job, besides construction, do you get to be outside all day long?" she says. "What other job can you set your own schedule? I thought about doing something else. Dispatching or something. ... But this is the best job I ever had.”

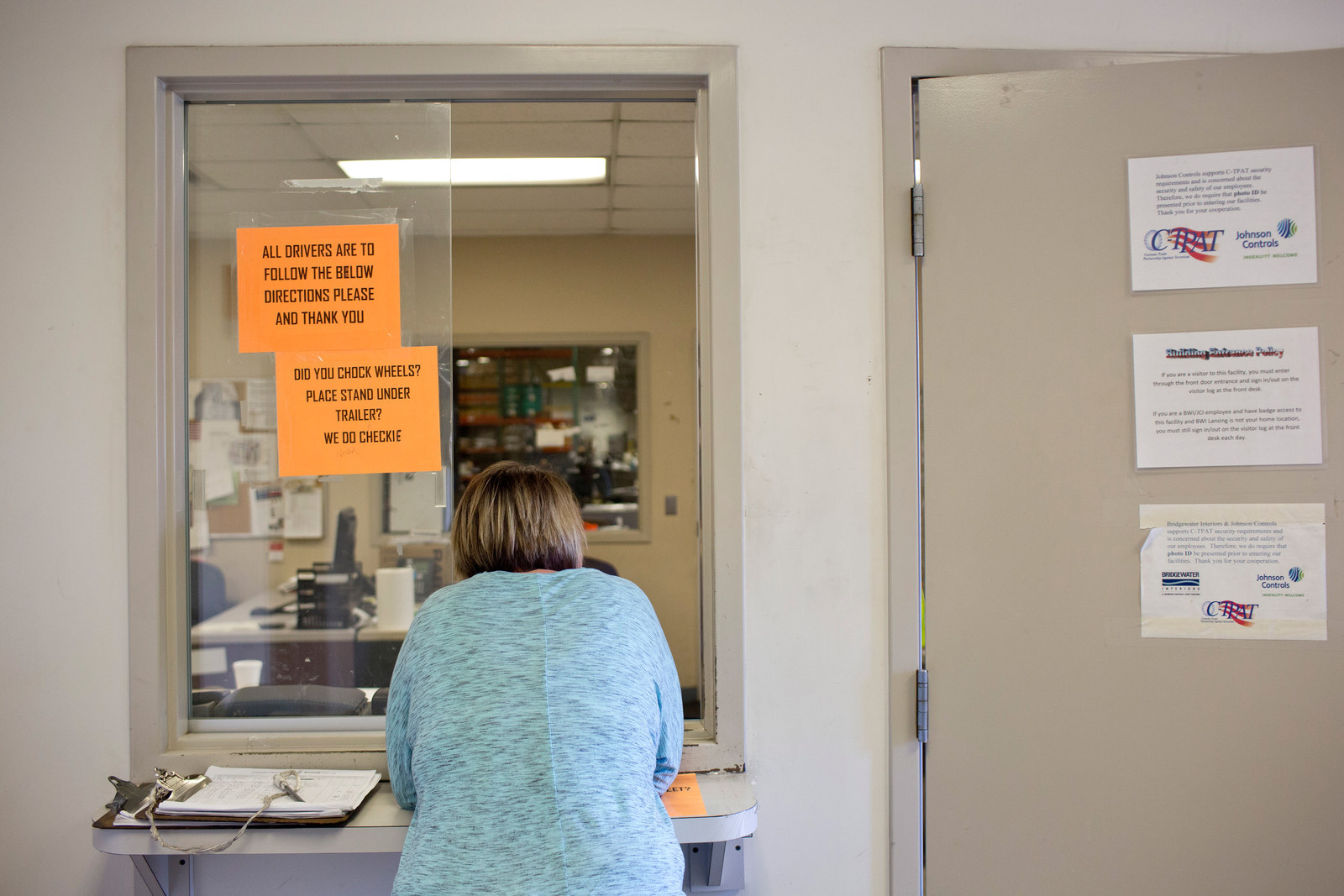

Our trip begins on a pristine Saturday afternoon at Rojas’s two-bedroom home in Coldwater, Michigan, on the banks of Cemetery Lake. After picking up her truck’s cab from its parking spot down the street, we take a 45-minute southwesterly drive to Kautex's warehouse in Avilla, Indiana, where we’ll retrieve a truckful of empty racks. An international automotive supplier that makes and distributes car parts, Kautex manufactures the smog-checking devices that we’ll be transporting back from New Mexico. Inside the warehouse, Rojas picks up paperwork from a matronly, bespectacled receptionist dressed in a highlighter-yellow safety vest, then returns back to the truck.

"The only trucker code that's out there now — but it's dying — is you help your brother."

Before every trip that they take, drivers are required by federal law to conduct a vehicle inspection. They check their brakes, steering mechanisms, lighting reflectors, tires, horn, wheels, and emergency equipment to make sure they’re functioning properly. These inspections are done again every morning before getting on the road, and once again at night before going to sleep. Drivers don’t always adhere to the rules, but Rojas — like many other women who get behind the wheel — is a stickler for precision.

“If you don't pre-trip your cab,” she says, “you’re an idiot.”

The truck Rojas and I will be living in for the next six days is notably enormous; imagine four grown elephants walking in tandem, trunk to tail. There’s a good 3 feet between the bottom of the truck and the pavement, into which Rojas, at 5'2", crouches easily to examine the brake lines, brake pads, tire pressure, and landing gear. She then climbs up between the cab and the truck — an area called the fifth wheel — to inspect air and electricity hoses.

It’s worth noting here that Rojas doesn’t allow the grit of the job to preclude any feminine beauty practices. Her asymmetric bob is freshly blown out and highlighted with pale streaks of baby blue and My Little Pony purple. Her acrylics glisten, rhinestone-pocketed jeans accent her physique, and her makeup is painted on with a deft hand — all of which proves a striking contrast to the greasy, oily gray of the machinery.

As she takes me on a tour of the machine, I point to the empty truck that will eventually house our cargo.

“What is this called?” I say.

Rojas looks down at me incredulously.

“The trailer?” she says. “Trailer” — she points again to the large compartment — “tractor” — she points to the cab. “Tractor-trailer. I have never been around anyone who is literally that clueless.”

"I have to realize," she will tell me later, "that there are people out there like you."

The brisk blue Indiana horizon is punctuated with cherry-red barns and cobalt tractors and golden rows of corn. Over the course of two hours, the two-lane farm road intersects Route 3, which eventually merges with Interstate 69.

The country's roads are almost part of Rojas's genetic makeup. Her mother and stepfather both operated long-haul commercial vehicles, as did her maternal grandfather. As a teenager, she was often left alone while they were on the road, and she swore up and down and on everything holy that she would never follow in their footsteps.

But in 2012, she was working three part-time jobs — bartending, cashiering at McDonald’s, and selling shoes — and still struggling to support herself and her children. One day, she was scrolling through Monster.com and an ad kept popping up. “‘Get your commercial driver's license! Make $60,000 a year!’” she remembers. “I did it because I needed money."

C1 Truck Driver Training, the school that ran the ads, put Rojas up in a hotel in Fort Wayne, Indiana, for four weeks of training. True to her genes, she was a natural.

"I took to it like a fish to water," she says. "It was not necessarily conducive to the home life I wanted to have, but it paid the bills — more than working at McDonald's for the rest of my life."

Rojas went on to work for three companies: USA Trucks and Schneider National — both of which are among the largest trucking companies in the U.S. — and her current employer, a mom-and-pop operation owned by Michigan-based Therese and Larry McComb.

The trucking industry has changed tremendously since Rojas’s parents were on the road; in the past 30 years, capitalist competition has erased the once-courteous relations between companies. According to the IRS, after the industry was partially deregulated in 1980, “the formerly gentlemanly manner in which the big players dealt with each other became a battle to the death.”

In the U.S., the largest trucking companies — including J.B. Hunt, C.R. England, and Swift Transportation — operate tens of thousands of vehicles each. Drivers are at the mercy of anonymous dispatchers, and can be on the road for months at a time.

The McCombs, on the other hand, operate five trucks. Larry McComb and Rojas talk on the phone daily, and he deeply understands the importance of getting her home to see her kids; the McCombs' daughter was killed by her husband in 2010, and they now run a nonprofit, The Venus Foundation, for victims of domestic abuse. Rojas’s bosses also allow her to bring her children on the truck if need be; they’ve come along over school vacations and long weekends, and Rojas briefly experimented with home-schooling them from the road.

For the McCombs to care so much about their employees is a breath of fresh air in an industry that’s plagued with problems. In addition to drivers being run into the ground with unrelenting routes, their pay has been tumbling for decades, many are beset with health issues, and sexual harassment is common enough that one major U.S. trucking company has faced multiple lawsuits in the past decade.

That company is Iowa-based CRST Expedited, which employs over 3,500 drivers and sends them on the road in teams. Often, women are paired with men for one-on-one, hands-on training. In 2007, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed suit on behalf of 270 female CRST Expedited employees or former employees who had allegedly been sexually assaulted by fellow drivers or trainers.

The allegations were shocking. In one instance, a female employee said that her trainer raped her on his truck after she turned down his bribery and advances. “He said, ‘Well, you give me a piece of your ass, and I will grade you and will pass you,’” she stated in her testimony. When she said no, “he force[d] me to have sex with him.” In another instance, a male trainer allegedly told his female trainee that he and his friends wanted to tie her up and “do things to her.” When she repeatedly turned down his requests for sex, he pulled out a knife, placed it on the dashboard, and refused to let her off the truck.

After reporting him to several of her supervisors, the trainee went up the chain to a member of CRST Expedited’s nearly all-male senior management team. “What are you going to do when they [harassing male drivers] kill one of these women?” she asked. The manager replied, “We'll deal with that when it happens.”

Though CRST ultimately settled with the lead plaintiff, the class-action suit was dismissed by a federal judge because the EEOC hadn’t met certain requirements before bringing the claims to court. (The EEOC and CRST Expedited have since been in a protracted legal battle over whether the commission should pay the company’s court fees, a case that is scheduled to be heard by the Supreme Court later this month.) In 2011, CRST was ordered in a separate case to pay $1.5 million to another former driver who alleged her trainer had raped her.

Most recently, in May 2015, another lawsuit was filed against CRST Expedited by three female drivers on behalf of an estimated group of over 100 women. It alleges that nothing has changed in the past several years, and that some women resorted to sleeping with knives and tasers under their pillows to ward off any attacks. CRST has since earned a nickname: Constantly Raping Student Truckers. (The company declined BuzzFeed News’ request for comment).

Desiree Wood, 51, founded the advocacy group REAL Women in Trucking in 2010 after constantly hearing stories about female drivers suffering sexual harassment and assault — herself included — and then being ignored by their superiors. “What I found was, [harassment and assault] wasn't just happening where I was working,” she says. And brushing off womens' reports "seemed to be the way they dealt with drivers. The easiest way to deal with a woman who’s complaining about sexual assault or sexual misconduct is to say she can’t drive, or she’s crazy, and make her go away.”

Rojas knows all of this quite well; at one of her old companies (she declines to say which one), she was sexually harassed by a colleague. She called her supervisor and insisted that the other driver be reprimanded. He was, but as far as Rojas knows, he was not fired. “I had asked that he be reprimanded instead of fired if it had been his first report,” she says. “I hate to see someone lose their job [but] I wanted him to be aware, women in our field will not tolerate such behavior.”

A general lack of attention to female employees’ safety exists despite the fact that the industry is desperate for more drivers; according to the American Truckers Associations, the trucker shortage in the U.S. was near an all-time high as of 2014, at 38,000 vacancies and counting. The group notes that the lack of women drivers is part of the reason for the shortage, and that they represent a "large, untapped portion of the population"

Efforts have recently been made to fix the problem, but trucking still poses major safety risks for women. Overnight rest areas are not overseen by security personnel, nor are showers or truck stops. (Driving equipment for women is even hard to come by; at a truck stop in Indiana, Rojas has to buy men's working gloves, which dangle off her fingers like a kid’s hand-me-downs.) With all this in mind, Rojas takes no chances. "If I ever have to stop at night where I don't feel comfortable," she says, "I will get out, and I will take my tire thumper with me."

"Guys will joke when I walk by, like, 'I didn't do it, I swear!' I'm like, 'Yeah,'" she says, hoisting her eyebrows, “'Keep it that way. ’Cause I'm not afraid to start swinging, buddy. If I catch you in the nuts, I don't care.’”

After leaving Avilla behind, we drive through Fort Wayne and Indianapolis, past idyllic churches and pastures and farmland. Before the trip, we exchanged a series of emails and texts in which Rojas let me know what to bring (clothes, toiletries, and snacks) and how much money I’d need (about $200). After learning that I drink upwards of four cups of coffee a day, she also told me that we’d go out of our way to hit the best coffee spot on the whole trip: Caribou Coffee, at the Joplin 44, a legendary truck stop in Joplin, Missouri.

We rumble southwest on Interstate 70 for seven hours, passing the time by swapping stories and a shared soft spot for country music, until the sun drops behind the western horizon. It’s 9:30 p.m. when we finally ease the truck into the Pilot Travel Center in East St. Louis, our first overnight stop. There are over 650 Pilots across the country, complete with gravel lots in which drivers can park and sleep, showers, lounge areas, and amenities. These are where we’ll spend most nights on the road.

Drivers are required by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) to take a certain number of breaks: Each day, they can drive for up to 11 hours within a 14-hour time period. During those 11 hours, they must stop for at least 30 minutes after eight hours of consecutive driving. After 11 hours have been completed or 14 hours have passed, they’re required to take a 10-hour break.

We circle the Pilot's sparsely lit lot, past trucks that are sardined together in rows, until we locate a free spot. I descend from the passenger side to guide Rojas in, not noticing at first the man standing about 30 feet away. He glances at Rojas, then calls out to me.

"It can be nerve-wracking,” he says, referring to her backing the truck up.

"She's a pro," I say.

He starts walking toward me, taking long hauls from a cigarette, until he's so close that I can smell the nicotine on his breath.

"Need a flashlight?" he says.

"No."

This does not dissuade him from keeping me company. When I give Rojas the signal to stop, he corrects me.

"She's got lots of room." Clamping down on the cigarette, he sticks his right arm out and twitches two fingers back and forth, motioning her forward until she's safely in.

After he walks away, I categorically insist that I had the situation under complete control. "Aw," says Rojas, "he was just trying to help."

Still, by the time we climb back into the truck after a quick bedtime routine conducted in the Pilot bathroom, Rojas has a final reminder before switching off the lights. "Please lock your door," she says, turning over in her twin-size lower bunk. "I don't want any...unwanted visitors."

Our alarms jolt us awake at 6 a.m. Between the bunk beds and the driver’s and passenger’s seats, we have just enough room to swing our legs over the edge of the beds and yank our pajama pants on — a cramped endeavor, but one made private by a brown pleather curtain that blocks the front and side windows. Rojas hauls out a behemoth gym bag full of supplies and clothing as I daintily procure my toiletry bag, a small floral number stuffed with beauty products, most of which remain untouched for the duration of the trip. We head toward the Pilot to shower.

We’re not the only ones awake; two men with trucker hats pulled low over their eyes shift from foot to foot, hands shoved in their pockets, waiting for free showers. A middle-aged woman with puffy eyes, rubber flip-flops, and neon-green rollers in her hair stands in line for the register, clutching an extra-large coffee. We shuffle to the front of the line, pay $13 each for showers and are given PIN codes that will open the doors to two shower rooms once they become available.

Five minutes later, a very pleasant woman’s voice comes over the loudspeaker: “Shower customers two and three, your showers are now ready.”

Down a long, white cinder block hallway that smells like chlorine, the showers are located behind brown wooden doors that look like they belong to elementary school classrooms. They’re surprisingly spacious inside, the floors tiled and spotless. Fluffy, chocolate-brown towels are neatly folded on a low ledge. The shower itself is Vegas-spa roomy, with filled shampoo, conditioner, and soap dispensers affixed to the wall beneath the showerhead.

It’s not until I finish my 10-minute wash, step out, and begin toweling off that I realize I haven’t brought a change of clothes and, as a result, will be walking back through the store still slightly wet, in my pajamas, with no bra.

If you’ve never walked around braless and freshly showered in public, it’s a tough sensation to describe, but it’s one with which Rojas is acutely familiar. It’s the same way she feels just getting out of her truck at rest stops. "It's like you're an ant under a microscope," she says. That’s why, she adds, when most female drivers stop somewhere, “we go in, we do what we have to do, and we get back in the truck, and we don’t get out. It’s not even about safety; we don't like the feeling we get out there.”

The bull's-eye of the United States is bisected, in part, by Interstate 44. Starting in St. Louis and ending near Dallas, the highway cuts a southwesterly trail through Missouri and Oklahoma.

God's country this is not. Indistinguishable warehouses border the interstate like gray Monopoly hotels. Thin, black telephone wires slice through the sky. It would be easy, as a driver, to drift into reverie here, to set the truck on autopilot and let the mind wander. Instead, Rojas takes these roads seriously. Three hours after we depart East St. Louis, another truck swerves into our lane. She doesn't hesitate. "I'm reporting his ass," she says, voice-dialing the local police. "Naw, dude. That shit don't work."

Later, we see a truck pulled over on the side of the road. "See, this drives me crazy," she mumbles. "Turn your damn flashers on to let somebody know you ain't moving!"

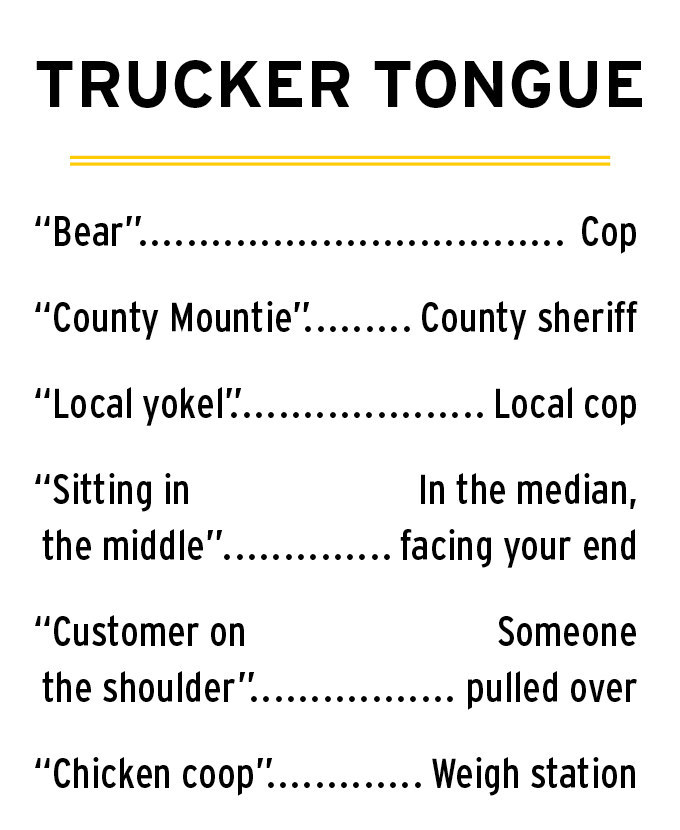

We lumber down 44 this way all afternoon, through Rolla and Springfield in Missouri, passing blown tires (known as "road gators" in trucker lingo), soggy cardboard boxes, and all the other disconcerting lumps that comprise our country’s highway debris. Rojas makes few stops, until finally, just past 2 p.m., we arrive at the Petro Stopping Center in Joplin, Missouri.

A multi-level, 23,000 square foot complex, the Joplin 44 is something like the Saks Fifth Avenue of truck paraphernalia. A lime-green truck with purple flame details greets visitors in the lobby. Chrome speakers, headlights, and taillights are displayed on the far wall, which is adorned with shiny black felt. State-of-the-art CB radios are exhibited behind glass cases.

On a mission for food and coffee, we pass through the truck goods shop and skip up a couple of steps, only to hit a bloated, XXL roadside gift shop. Our path to coffee heaven is now blocked by Jesus paraphernalia, Beanie Babies, snow globes, greeting cards, ceramic animals, bobbleheads, shot glasses, keychains, and whimsical wall hangings with cliché sayings such as There's Always Time for a Glass of Wine!. We bob and weave, trying not to get distracted, until we finally come out to a food court. Lines have formed loosely in front of our five options — Dairy Queen, Taco Bell, Pizza Hut, Caribou Coffee, and Orange Julius — and once we've secured our lunch, we sit down and enter what can only be described as a fast-food black hole. Time loses all meaning. Space takes on warped dimensions. Flavors blend into a kaleidoscope of salt and cheese and then, blissfully, sugar. When we come to, we are two chili cheese dogs, two burritos, one ice cream, and two frozen coffees down.

Rojas was right about the coffee. I put away a 24-ounce Mint Condition Mocha Cooler before we stagger back outside — already sweating out our lunch — shield our eyes from the sun, and lumber back into the truck.

An hour later, we pass a Walmart superstore with dozens of trucks parked in the lot. Walmart, Rojas explains, has a unique business model when it comes to transporting goods: They hire their own fleet of drivers, meaning that drivers don’t have to deal with getting lost in an outside corporation's fleet of employees. Most other retail companies contract out with one of the major trucking companies, and employ an intermediary to warehouse goods that drivers pick up. It’s a standard business model that Rojas and her peers believe, probably rightly, that the majority of Americans are ignorant about.

"Most people don't think a lot about how they get the fruit juice or paper towels on the shelves, " she says. "If it weren't for us, you wouldn't have food. You wouldn't have clothes, toilet paper to wipe your ass with. How do you get steaks? A cattle farmer sells the cattle, a butcher chops it up, we bring it to you." She’s right: In 2014, trucks moved 9.96 billion tons of goods in America, accounting for 68.8% of all domestic cargo.

And yet, myths and truths about the industry abound, so I take this opportunity to ask Rojas some questions that have been on my mind since before we met.

"If it weren't for us, you wouldn't have food. You wouldn't have clothes."

“When you’re driving on a two-lane road and two trucks block you in, are they doing that on purpose?”

“No,” Rojas says, not a single beat missed. A lot of trucks are rigged to stay below 61 or 62 miles per hour, she explains, meaning that if they’re trying to pass each other, it takes a long time. “They're going at a snail's speed. They're not doing it on purpose.”

“Are there drivers who take pills to stay awake on the road?”

“I imagine there are,” she says. “I imagine there are. [But] you do any of that, you get busted, you lose your license. You lose your livelihood. So why anyone would take that risk, I do not understand.” Drivers she knows are more likely to hit the caffeine to stay awake, she says, or to smoke, just to have “something to do with their hands.”

The bigger problem — at least among drivers Rojas knows — is the physical toll of the job. Long-haul truck drivers are at risk for spinal problems, hip and knee problems, and high levels of anxiety and depression. According to the CDC, they’re also twice as likely as the general population to be obese or morbidly obese, to smoke cigarettes, and to have diabetes. “These guys have serious health issues,” says Rojas. “I recently saw a 400-pound dude squeezed between the steering wheel, with two bags of McDonald’s and two bags of Subway.”

These types of health problems were likely always there for the men and women who drove trucks. But most popular fast-food chains weren’t established until the 1950s. And isolation was less of an issue; drivers used the CB radio to make small talk with one another, and developed a sense of community. The romantic feeling that truckers once had about their jobs — whether real or imagined — led to a mythical American trucker code, in which drivers helped one another at any cost, assumed their best intentions, and understood their gypsy souls in a singular way.

But all that's changing, as the government has begun to implement regulations that drivers don't agree with. In 2013, the FMCSA instituted several rules, including one staunchly opposed by the trucking unions that would have dictated what time of day drivers must take their breaks (the rule was subsequently suspended in 2014). In December, the FMCSA also mandated that within the next two years, all truck drivers must have electronic logging devices in their vehicles, a system many bigger trucking companies already use. With arrival times reported to their companies to the second, drivers can feel like there’s zero room for error. Plus, says Rojas, “it takes the [work] out of actually doing the math — so it puts a lot of dumb drivers on the road.”

Those making these changes are mostly legislators and corporate CEOs, says Rojas. "It's people who have no idea what it's like to do this every freaking day, for years on end," she says. "They're coming down on us."

Because of the industry’s growing corporatization, the once-sacred code is getting lost. Formerly a small, proud, and tight-knit community, trucking is becoming a last resort for people with nowhere else to turn, she says. "People come into this business because they are at rock bottom," says Rojas. “There’s a lot of money to be made. The only trucker code that's out there now — but it's dying — is you help your brother. You see someone broken down, you pull over and help them.”

Thanks to the lack of accountability that comes hand in hand with the lack of community, Rojas doesn’t always feel comfortable inserting herself into that brotherhood. “I wish I was part of that,” she says. “But honestly, for my own safety ... honestly, I can't."

As we drive through Oklahoma City on Sunday evening, the sun is beginning to set in the west, casting a blinding blood-orange hemisphere of light over the city. A state fair slowly rolls into view, all Ferris wheel lights and corn dog booths and rickety roller coasters. Rojas keeps her gaze locked ahead. "I used to date a carnie," she muses. "He had one eye."

Silence for a moment.

"The guy I dated before him had one eye too," she adds. "Nice guy, though."

Weatherford, Texas, is hot and dark just past midnight on Monday. When we pull into the local Pilot, Rojas swings out of the truck, pulls out her phone, and immediately opens Facebook. Social media is “a way to stave off loneliness on the road,” she says. She scrolls through her own photos, photos of friends, and friends' pages as we walk up to the attached Wendy's, populated by a pimply teenager behind the register, a drunk-looking gentleman swaying on his feet, and an exhausted-looking lady slouched into a corner booth. "Look at this," says Rojas, exclaiming over a cat-themed meme.

Facebook not only keeps truckers entertained, but also helps them facilitate communication. “We have groups,” Rojas says. “There’s weather reports, there’s Twisted Truckers, which is more for people wanting to make fun of other drivers, but also again we use it as a learning tool. ‘Here’s a person who had a really bad accident, here’s why’ kind of deal.” One recent image posted to the Twisted Truckers page — which has been liked by over 350,000 people — showed a truck rolled onto its side and wedged against a concrete bridge support, with the caption, “Just pulled over to scratch my forehead.”

Rojas briefly looks up to order food, then returns to her own Facebook page. It’s full of selfies from the road and from home; photos and videos of her two cats, a Siamese kitten and a black-and-white Billicat; links to articles about truck accidents and weather conditions; and inside jokes among her friends. It’s also loaded with lovingly shot pictures of her kids, many of which she took herself.

For the most part, Rojas is upbeat and determined. But she knows what it means to be a trucker’s kid. Her parents — who met after passing each other constantly on I-95 — were gone for long stretches at a time, often leaving her alone at their family home in Geneva, New York, to fend for herself. Her stepbrother checked in on her periodically until she was old enough to drive a car. Then she was on her own.

“It’s a hard life," she says. "My friends were envious; I had no babysitter, just calls from the road, like, 'You alive?' I made it look like I had the best life, but it was a sad existence."

Rojas talks to her kids as often as she can from the road. She tells her ex-husband, who watches the kids while she’s gone, that they can call whenever they want. When she’s stopped, she’ll message them on Facebook or text. But in the late hours of the night, it’s hard for her to forget that her kids might be feeling, on some level, the same things she felt as a child.

"They tell their friends, 'My mom's a truck driver!'" she says. "They're proud of it. But I have had to miss some events due to driving. I missed an awards ceremony this year. [My son] got student of the month.” Technology helps. But it doesn’t always make things better.

“[My daughter] goes in spurts,” she says. “Sometimes she texts, 'Mom, Mom, why aren't you picking up?' 'Honey, Mommy loves you, but I can't text and drive.'”

Texas highways are notorious for their mind-numbing sameness. The side of Interstate 20 is parched and straw-colored for hundreds of miles, and the speed limit is 80 mph, as if to offer a sly nod to the sheer monotony of the 600-mile stretch.

By the time afternoon rolls around, ennui has taken hold. Rojas and I have talked all we can talk. I have conducted every preliminary interview I can think of and then some. She has sportingly put up with it.

It’s been three days.

If Rojas were alone, as she usually is, she would pass the time by calling her kids, her family, or a list of about five friends she talks to daily, one of whom she calls “Preacher.” It’s an appropriate nickname, given their standard topics.

“We love to talk about religion,” she says. “It’s more of a really active discussion about what we disagree about. … I think that we are a millisecond in God’s timeline. We are just a speck of dust on whatever table he’s working with. Everybody tries to humanize him, and his entity is not [human], by any means.”

Pause.

“So, we usually talk about shit like that.”

When she can’t get anyone on the phone, Rojas bulldozes through audiobooks. The last series she fell in love with was The Hangman’s Daughter, a five-parter about an executioner in 1600s Germany. Before that, it was any book by British author Robert R. McCammon. Earlier in the year, she listened to My Sister’s Grave. In the course of four months, she’s played over 15 books.

“I love to read,” she says. “What can I say?”

“I'm not Martha Stewart. I'm not Leave It to Beaver's mom."

Now, about two hours before we arrive in El Paso, she turns on The Atlantis Gene, the first installation in a trilogy that follows a geneticist and a government operative tasked with saving the human race. As the sunburned horizon whips by, our heroes switch sides, lose life-or-death items, get kidnapped and then rescued in the nick of time. This is a rare dabble into science fiction; typically, Rojas listens to historical fiction. “I love hearing the characters,” she says. “The way they speak, the way they carry themselves, the wardrobe, the way times were versus the way they are now.”

Sometimes, Rojas passes the time by thinking about what she’ll do once her kids are out of the house in 10 years. She’ll be 45, and she plans to visit the places she’s heard so much about. Italy is first on her list. “Just to be there, at the Colosseum, at the Parthenon,” she says. “I would love that."

Until then, though, she’ll be running this route. "It's nice knowing that with the paycheck coming in, I can feed my family,” she says. “I don't have to think about what check I'm gonna cut from to buy school clothes or go see a movie."

"There's different ways to take care of your family,” she adds. “I'm not Martha Stewart. I'm not Leave It to Beaver's mom."

Rojas then drops the subject, reaching over to crank up a song by punk-country singer Elle King. The chorus runs: I'm not America's sweetheart / But you love me anyway.

We arrive in Santa Teresa, New Mexico, just before 7 p.m. on Monday, and the sunset is hypnotic, all blazing purple and crimson red. A woman greets us at the warehouse’s reception desk after Rojas backs into the loading zone, and two men then begin hauling the smog-checking devices onto the truck. We have dinner at a nearby diner while they finish (it takes about two hours), then spend the night in the warehouse parking lot.

It's still pitch black when my phone’s piercing alarm starts chirping in my ear before dawn. I swing my legs over the edge of the top bunk, and Rojas does the same in the bunk below. We grunt greetings to each other, and she rubs her eyes, pours herself some water, and puts a bandana over her hair. She then goes straight to the driver’s seat, and we’re on our way back the same way we came.

Tuesday flies by against the Texas highways from yesterday. By the time we clear the rainstorm into Arkansas on Wednesday afternoon, the road has gone from cracked desert to lush Southern greenery. Rojas clicks the CB radio on to see if anyone has more information about the weather.

"Brake check, boys, they're pulling a car out of the ditch," a man’s voice says.

"Car just cut me off... [inaudible] license out of a Cracker Jack box," adds another.

"As long as you're laughing, that's all that matters, driver," a woman replies.

Alongside Interstate 30 in a small town just outside Little Rock, churches fly by faster than I can count them. A Baptist church on the right. Another one on the left. A Pentecostal church immediately after that. Within 30 minutes, we pass nine more houses of worship — 12 in total — along with a handful of tattoo parlors and liquor stores, a fireworks shop, and a bar called the Electric Cowboy.

Despite her regular conversations with Preacher, Rojas isn’t particularly religious. But she does keep a pink Bible laid out on the dashboard, dog-eared at Proverbs 31. It’s a passage that praises hardworking, independent women: "She seeketh wool, and flax, and worketh willingly with her hands,” it reads. “Let her own works praise her in the gates."

“That,” says Rojas, "is essentially the woman I strive to be."

The gray clouds begin to break up on Wednesday afternoon as we pull into the Petro in North Little Rock, Arkansas, to meet one of Rojas’s driving buddies, Edward Gruszczynski, who’s passing through the same town. The asphalt parking lot is wet from the rain, and the truck stop is full of people who don’t appear to be associated with any trucks, just locals there to pass the day. Gruszczynski is 31, sporting a faded black T-shirt, jeans, and what he calls a "road beard." Like Rojas, he works for a small company, and waxes nostalgic about the old days.

"To the bigger companies, you are just a truck number," he says. "The whole community of being a truck driver is being killed by corporate structure. My boss wants to know everyone by name, and face. It's like a family. This is how trucking used to be."

"Where do truckers go when they go on vacation? Home."

Gruszczynski has two children at home, ages 13 and 5. "I'm out, gone for a week, home for the weekend to see my kids," he says. "My little one, every time I get home, he's like, 'DADDAYYY! I want to go with you!'”

Rojas and Gruszczynski used to talk nearly every day on the phone for up to an hour, but they’ve since fallen out of the habit. Otherwise, he occupies himself by writing short stories. "I got a recorder I dictate them into,” he says. “But it's lonely as shit."

We wrap up our meal and head outside, but before we part ways, Gruszczynski leaves me with a joke. "Where do truckers go when they go on vacation?" he says, stubbing out a menthol cigarette.

"Home."

The Pilot in West Memphis, Arkansas, is almost completely unlit when we coast in at 9:42 on Wednesday night. Off Interstate 40, just after the Interstate 55 split going east, the station sits down the street from Southland Park Gaming and Racing, a casino that’s about three times the size of a typical Vegas betting parlor. At the entrance to the Pilot’s lot, a makeshift stand with a low-slung white banner that reads “METALS” greets visitors. To the left, there’s a margarita bar with a flickering, rainbow-colored neon sign.

The last time Rojas came through this area, her employers insisted on putting her up in a nearby Motel 6. "It's a drug house and a whorehouse," she says of the motel. "But they'd rather have me stay there than in this lot."

The Pilot is known for prostitutes — whom drivers call “lot lizards” — and for an undercover narcotics cop who's worked the area for years, trying to bust truckers over the CB. As if on cue, the radio spits on: "Don't send her over here," says a man's voice, referring to a prostitute on the lot. "I got my old lady and her five sisters."

"The party is in your pants over there," a woman responds.

The man replies back: "Whaddya say the party's in your mouth, and we're all coming."

And then, another man's voice: "Big Dog, Real Deal. Take it to channel eight. Got a lotta what you need, satisfaction guaranteed."

This, of course, is the very narc about whom Rojas warned me. But it seems Real Deal is not going to get very far tonight; as soon as he spins his carefully crafted entrapment, three drivers immediately weigh in: "Yeah, 'Real Deal'; he busted me last year."

"Go to three-three if you wanna get busted by the police."

"The only place you're gonna find a real deal is in jail, mister."

We circle the lot twice more. It’s full of trucks, but no one is outside their vehicle. Finally it becomes clear that there's nothing else to see, unless we hop out and start asking questions, which Rojas does not give me time to ask to do.

"Think you got enough?" she says, already pulling out of the lot. "’Cause we're leaving."

By 6:15 p.m. on Thursday, we're back at Kautex to drop off the load. The lot is empty again, and the process is swift. Rojas backs into a muddy parking spot, unhooks the trailer, and pulls out — no paperwork is involved, no checking in, and after we’ve disengaged the cab, we take off toward her house.

The sky is a pristine cerulean blue on the way home, and we can't drive a half-mile without passing a quaint barn straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting. It’s the kind of place anyone would be itching to get back to. We pass over the St. Joe River, which is so sparkly that Rojas insists I get out and take a picture. As I do, she calls out to me through the window.

"Hurry up!" she says. "I want to go home." ●