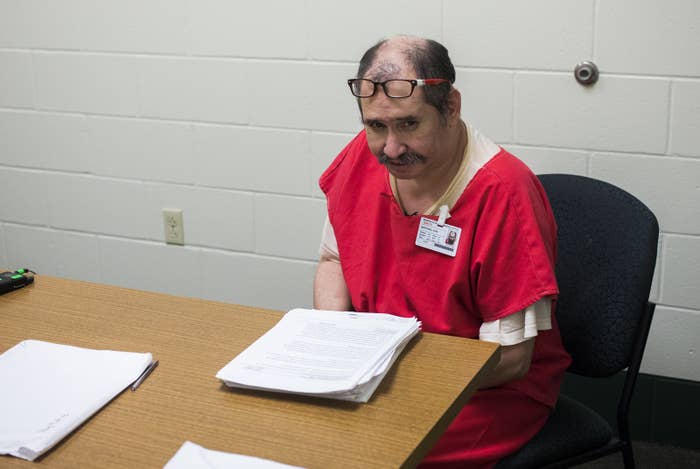

OCALA, Florida — The confessed drug cartel hit man Jose Manuel Martinez had already been sentenced to 10 life terms in prison by the time he was sent to Florida to face charges on two murders here.

But Florida prosecutors thought they could do something that California and Alabama prosecutors could not: They thought they could get a death sentence.

After all, he had told multiple police detectives from multiple states about how he had killed three dozen people, many of them on behalf of drug cartels, over a 30-year run of impunity.

If the death penalty wasn’t appropriate for someone like Martinez, who sometimes laughed as he described the damage his bullets did, prosecutors asked the jury, then who was it right for?

But prosecutors hadn’t counted on the impact on the jury of hearing from more than a dozen members of Martinez’s family, who testified, often through tears, about how he had sacrificed himself to protect his siblings during a brutal childhood in California’s Central Valley and how he took his children and grandchildren to Disneyland and on swimming adventures.

At the end of the three-week trial, after less than two hours of deliberations, a jury of seven women and five men decided late last week to spare Martinez’s life. For the 2006 murders of Javier Huerta and Gustavo Olivares-Rivas, whose bullet-riddled bodies were left to rot inside a Titan truck parked at the edge of Florida’s swampy Ocala National Forest, he was instead sentenced to two more life terms.

Martinez said that he executed the two men because Huerta had stolen 10 kilos of cocaine from Martinez’s employers. In the course of the killing, Martinez recovered $210,000 in cash, some of which he gave to his mother, and some of which he spent on a quinceañera party for one of his daughters.

One of Martinez’s lawyers, John Spivey, said the case came down to two opposing visions of his client: “the cold killer executing people for payment for over 30 years” versus “a truly dedicated father, uncle, grandfather.”

“The human side outweighed the monster side, in the end,” he said.

After the jury gave its verdict, one of the defendant’s daughters, Joanna Martinez, cried in the courtroom. “I know it was in God’s hands,” she said. She added that she was “sorry to every single person that my dad has caused suffering. I’m sorry on his behalf. I hope they can find peace.”

Jose Martinez, whose reign of killing was chronicled in a BuzzFeed News investigation last year, was born in California’s Central Valley. He committed his first murders before he was 18 — to avenge, he said, the murder of a beloved sister.

His first murder-for-hire came shortly after his 18th birthday. He continued to kill with near impunity for more than three decades. By his own account, Martinez committed murders in Washington, Idaho, Oklahoma, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, and Colorado. But the worst of his violence was inflicted in the community where he was born and raised: the sunbaked flatlands of California’s San Joaquin Valley. Police there suspected him in numerous murders but never charged him.

As to how he got away with it, Martinez simply said he was “so damn good.” He left little evidence and few witnesses. But a key element of his success was that he understood the stark injustice of American law enforcement: Kill people who don’t matter — who are poor, who are immigrants, who may be criminals themselves and don’t have anyone to speak for them — and you can get away with it.

In the end, Martinez gave himself up to save his family.

It started in 2013, when police began investigating a murder in Alabama. Martinez had killed the man, an acquaintance of his daughter’s, as revenge for his calling her a bad mother. But in Mexico, where Martinez was safely out of reach of US law enforcement, he heard that police were planning to call his young granddaughter in for questioning. That he could not abide.

He came back to the United States and confessed to the murder. And then he kept going.

When T.J. Watts, a Florida detective investigating the 2006 cold case murder of Huerta and Olivares-Rivas, came calling, Martinez confessed to murdering them, too. Martinez also told Watts that it was “time for me to pay for all the things I’ve done in my life.”

Martinez insisted that unlike other contract killers, he lived by a moral code. He tried to kill only the intended target, not their family members. And he killed men, or so he at least claimed, who had hurt women or children.

Martinez pleaded guilty to one murder in Alabama and nine more in California, receiving multiple life terms. Then he was extradited to Florida.

It took jurors less than 30 minutes to decide that Martinez had murdered Huerta and Olivares-Rivas in cold blood. Then prosecutor Amy Berndt made the state’s case that he should be put to death.

She acted out some of the other murders for which he had been convicted, holding up her fingers in the shape of a gun. Current and retired detectives from around the country showed videos of Martinez confessing.

The jury also heard from the wife of Martinez’s first murder-for-hire, Cecilia Camacho. She told the jury what it was like, as a 21-year-old mother on her way to a day of work in the olive fields, when someone sped up beside them and shot her beloved husband in the head.

For three decades, until Martinez confessed, she never knew who had killed him or why.

Then it was the defense’s turn.

Throughout his long run of killing, Martinez had been lucky. Police had made mistakes, overlooking evidence that was sometimes right in front of their eyes. Even when Martinez had been a suspect, police had not charged him.

Now, with his life on the line, he got lucky again.

He got a public defender who was a seasoned trial lawyer in capital cases, working for an office that was prepared to spend money on experts and cross-country trips to interview witnesses.

Martinez’s lawyers brought in medical experts to argue that his brain was irreparably damaged from a head injury he’d suffered as a young man. He was a product of incest, they noted. His mother had been raped by her own uncle. They called in trauma experts to talk about his childhood amid violent drug traffickers and how it had given him a “skewed moral code.”

And finally, they flew in nearly 20 members of his family to testify about how much they loved him.

Daughters, sons, nieces, grandchildren — all told the jury a version of the same thing: He has done bad things, but he is always there for us, the one who takes us to the hospital, who makes us laugh away our tears, and who comes up with the money for doctors and funerals and other expenses.

Patricia Martinez, the defendant’s younger sister, told the jury the lengths to which her brother had gone, even as a child, to protect her. “He’s been more than a brother. He’s my guardian,” she said. “I’m alive because of him. He took beatings for us. He fed us. He saved me.”

The jury was out for two hours before coming back to say: No death penalty. Judge Anthony Tatti sentenced Martinez and offered him the chance to say something, but Martinez declined.

But afterward, Martinez said the testimony from his family saved his life.

Prosecutors declined to comment.

Cecilia Camacho was back home in California when the verdict was announced. She had remarried and had more children with her second husband. She worked picking oranges for decades to help send those children to college, and on to successful careers. The family was shocked that the jury had not voted for death, a relative said.

Camacho was philosophical: No matter what punishment they gave Martinez, her husband was still gone forever.