A year after my parents divorced, my mother’s postcards began to arrive in the mail.

She had only ever taken two big international trips before then: When she moved to America from South Korea in 1976, and when she and I visited Madrid in 1998. For the latter, my sister Laurie was studying abroad and we stayed with her over Christmas — a miserable two weeks consisting mostly of our mother’s endless grousing, due to the absence of kimchi in Spain. Nearly a decade had passed since then when, to my surprise, my mother started traveling the world alone. I discovered her whereabouts solely through the notes she sent, from Buenos Aires, Amsterdam, Beijing, Paris. After visiting the enormous soapstone statue of Cristo Redentor in Rio, she proclaimed via email: “You can spread my ash on the Corcovado.”

Meanwhile, I lived on the smelliest block in Manhattan. No hyperbole here; New York magazine officially crowned my old block the stinkiest stretch in the city. But back when I was 21, roosting on the border of Chinatown and the Lower East Side, my neighbors and I did not need outside confirmation. We were all too familiar with “the Stench”: a rancid mélange that smelled like cat urine and raw sewage mixed with expired poultry. The source of the Stench could be traced a few doors down from my apartment building, to a trading company whose generic warehouse appearance obscured what existed, putridly, out of view.

When you’re young and broke in New York, making certain concessions for a steal seems appropriate, if not savvy. I’d scored a rent-stabilized lease in a tenement building downtown, so I accepted the apartment’s rank location, and in my mind, rebranded the many other glaring shortcomings as “quirks.” Like the fact that management stored open trash bins in the dank lobby, where posted signs read in English and Cantonese: No Spitting (bilingual friendly!). My elderly neighbor Agnes, who spent her days in a wheelchair, kept her door propped open with a long metal charley bar. This allowed the sharp scent of urine, overlaid with bleach, to waft down our shared hallway (wacky New York character!). My bedroom window faced a brick wall (privacy!). The foot-long gap between the wall and my window also functioned as an attractive thoroughfare for chatty stray cats, pigeons, and rats.

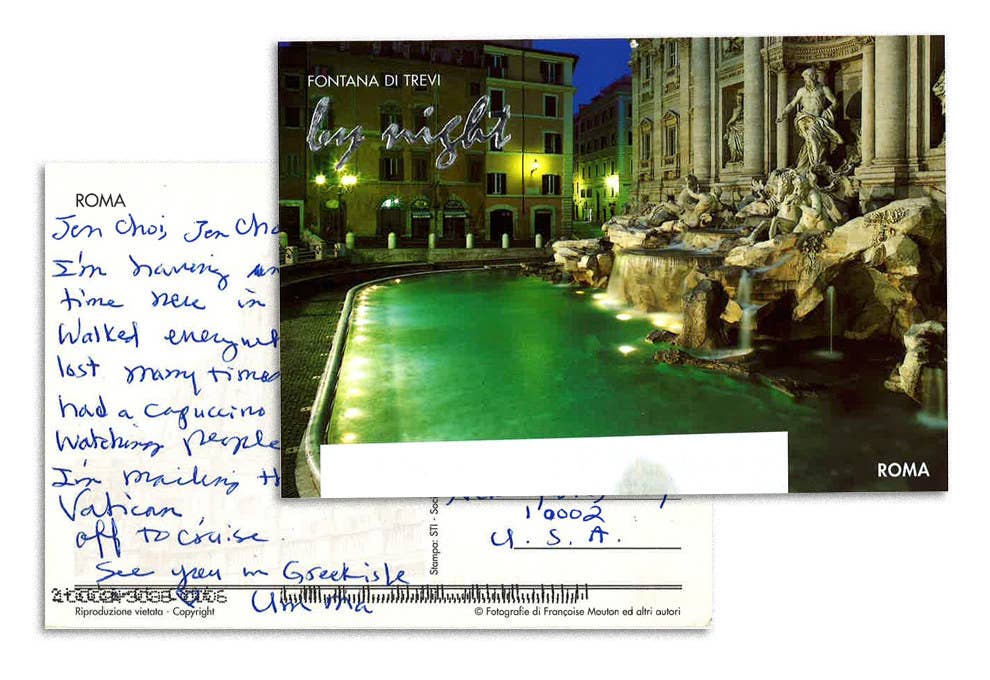

I unearthed the first postcard one rainy afternoon. To get to my mailbox, I’d dodged empty milk cartons and Table Talk miniature fruit pie boxes Agnes had chucked down the hall. A picture of the Fontana di Trevi practically glowed between Con Ed bills and junk mail, its fluorescent green water dappled with spotlights. On the back, my mother had written from the Vatican: “Walked everywhere, got lost many times & all…had capuccino on street.”

A few weeks later, I found a new postcard, depicting a lush coastal town bordered with cheery red flowers. “Mt. Etna was visible with smoke coming up,” she’d scribbled in Sicily. “After a day at sea, next stop is French Riviera.”

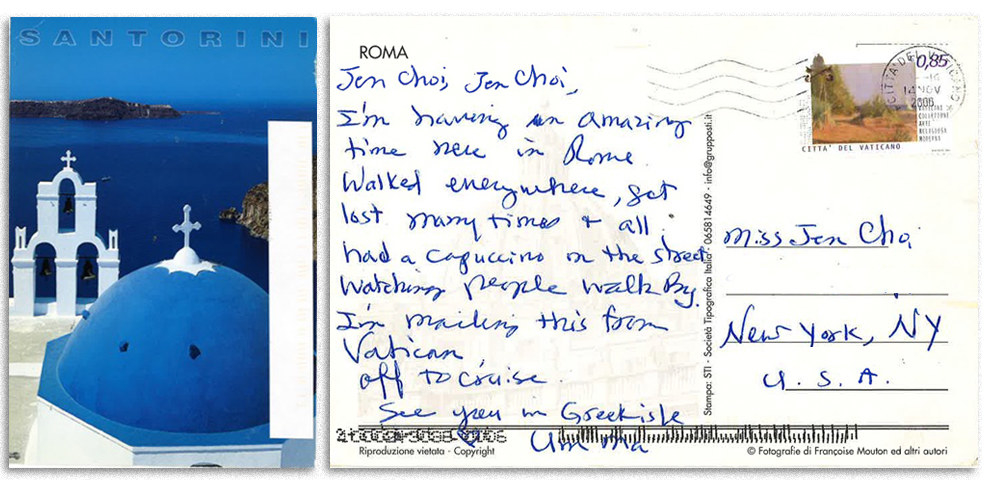

She dispatched the most curious message from Santorini, Greece: “I came down on a donkey. It was tough. By the time I got to the bottom of the steps, I was able to enjoy & had to get off the donkey. I sang & called you & your sister’s name over & over. Can you imagine?”

I couldn’t. What would possess a woman to scream our names across the Mediterranean while riding sidesaddle on a donkey? In my sunless apartment, I examined the postcard’s photo: the elegant masonry of a whitewashed plaster church, its crosses emboldened against a cobalt sea. Then I stashed my wine key in my pocket and headed for work at a nearby German biergarten, where I poured comically oversized steins of lager to petulant day traders well into the wee hours of the night before returning home — to the Stench, and the trash, and Agnes, and my scenic view of a brick wall, still wondering if what my mother wrote was true.

My mother hadn’t always been an adventurer. When I was growing up, she presented herself to the world as a woman of unflagging practicality: our breadwinner, taskmaster, and domestic dictator; the open-heart surgery nurse who wore beige sweater sets from a store called Petite Sophisticate, who donned a sensible, chin-length perm she blow-dried straight, who rarely, if ever, smiled.

I suspected a steely sadness to her resolve though, which I’d glimpse whenever she cleaned our shower. The stall was very small, as slim as an airplane lavatory. Every week she locked herself behind the mottled glass door, naked, clutching a squeeze bottle filled with noxious disinfectant. I was about 10 when I stood by the sink one Saturday afternoon to observe her routine. Steam billowed as she sprayed the tiles and scrubbed the grout with manic flourish. I watched the acrid mist swell, pinching my nose shut, horrified and amazed by her compulsion. Now this act strikes me as some private exercise in pain: how much she could take and tolerate, how much she believed she deserved.

Every week she locked herself behind the mottled glass door, naked, clutching a squeeze bottle filled with noxious disinfectant.

The closest I remember being to my mother happened around the same age, during our preening rituals. My small hands would part her hair this way and that. By her request, when I’d find a white patch, I’d pluck out all the offending strands, which looked like woven silver beneath the lamplight. Or I’d lie down and she’d gingerly clean my ears with a tiny wooden scoop. We groomed each other as monkeys do, building a quiet closeness. In these moments, she dropped her impenetrable veneer and let me in.

Rarely did she allow her inner anguish to roil to the surface. But I do recall several nighttime car rides together, when Patsy Cline’s “Crazy” played on the radio. She’d crank the volume and sing along, bawling: “Crazy, I’m crazy for feeling so lonely. I’m crazy for feeling so blue…” Each time I wanted to ask what was wrong. But her gaze remained fixed on some unknown distance, and I knew not to disturb her. Once the song ended, she’d zip up her misery, and we drove on.

Patsy’s song was about heartbreak. And yet, not once had I witnessed my parents kiss or hold hands. I’d wondered if this was a Korean thing. Both my mother and father had been born and raised in Seoul, a place as familiar to me as Mars. Laurie and I grew up in a sleepy, Southern California suburb. Half an hour east from us, in Hollywood, studios cranked out rom-coms by the dozen. My parents’ affectionless marriage, in comparison, seemed at best a lesson in mergers and acquisitions. It appeared as if for them, there hadn’t been any love to lose.

Ten years after those car rides, my father had an affair with a secretary at church, my mother’s single social space outside of work. To be betrayed in public is a particular kind of humiliation. But what I hadn’t realized as a child was this: When she sobbed to “Crazy,” my mother wasn’t mourning a loss of love, anyway — what she so achingly longed for hadn’t transpired in the first place.

Once my parents officially split, my mother stopped eating and dropped to a skeletal 90 pounds. She subsisted solely on boxed Franzia merlot for months. Whatever chilly fortitude she’d clung to sloughed away, leaving her shivering and raw, her whole being an open wound. I called her from New York. She wept feverishly for weeks, and I listened.

In 2005, shortly after the divorce, my mother relocated to a gated city called Canyon Lake, two hours southeast of Los Angeles. Unlike gated communities, gated cities (of which five exist in California) boast their own city halls, chambers of commerce, country clubs, and grocery stores, which are all locked behind town boom barriers, monitored by 24-hour community patrol.

When she sobbed to “Crazy,” my mother wasn’t mourning a loss of love, — what she so achingly longed for hadn’t transpired in the first place.

My mother chose Canyon Lake because she said she wanted to see beauty every day. She enjoyed the idea of passing picturesque shoreline views on her commute to work, like some morning meditation. Never mind that pumpkin-colored men blasted Limp Bizkit on their boats while skittering by the mini lighthouse on the man-made lake. Or that residents preferred cruising the streets in flame-painted golf carts instead of their regular cars. Or that beyond the guarded gates a grim and parched expanse, speckled with dead grass and half-built model homes, extended beneath a scorching sun in every direction.

When I visited my mother in Canyon Lake for the first time, she’d finally stopped crying. She’d also dyed her black hair orange, teased and pinned it aloft with glitter-spangled butterflies. She’d swapped her sweater sets for sequined baby-tees that proclaimed Cutie Pie, and wore a pair of flared blue jeans adorned with appliquéd houses, purchased from the children’s age 10–11 sale rack. “They only $7.99!” she bragged. “How can you beat that?”

She smiled deliriously, as if to distract me from something. And then I saw it, in her eyes: the same look I’d seen from Agnes, my old neighbor across the hall. Besides the army of young roaches that streamed out of her home, Agnes lived alone. Whenever I stopped by, which was far less often than she requested, Agnes held my hand and pulled me close with an urgent grip. Cataracts may have eclipsed her pupils with a gray fog, but the way her eyes quivered resembled my mother’s then — they shared the same barely tamped, quaking desperation.

My mother needed me in Canyon Lake, but rather than rest by her side as I’d done as a child, I turned away. Perhaps cruel, but I couldn’t parse which version of her she might summon next: the starved and drunk mother, electric with grief, or the inscrutable one hiding behind our shower’s mottled glass door. I’d suffered a loss too, anyway — one I’d yet to fully comprehend. In comforting my mother, whatever threadbare relation I’d maintained with my father over the years disintegrated for good. He did not reach out to me on my visit, or for that matter ever again. I felt hollow in Canyon Lake, like a conch gutted clean. So I flew back to New York, leaving my mother behind the walls of her desert mirage.

I don’t know how I procured her vacation photos, or why they appeared in my apartment one day. Whatever the case, they document a particularly mysterious period of my mother’s life: the year after I left her in Canyon Lake, when she decided to up and ditch her gated town in favor of jet-setting around the world. My mother has moved many times since then, so it’s possible I’d gained the pictures for safekeeping.

At 28, I no longer lived on the smelliest block in Manhattan. I’d relocated to a sunny second-floor walk-up in Brooklyn, though saddled with a new gloom. I was still bartending, now in a speakeasy whose gypsy jazz soundtracks snapped my own life’s anachronisms into focus; the rift with my father, the stagnant writing career I’d claimed to pursue for years, both frozen in time.

It is a strange thing to stumble upon someone else’s private memories. Dozens of unflattering, low-angle shots my mother had taken of herself (in a pre-selfie era) filled the rolls, with landmarks or her face accidentally cropped out of the frame. The leaning lower half of Pisa, for example. My mother’s chin aboard a London double-decker bus. Her orange hair wind-socking into a Roy Orbison–esque pompadour off Copacabana Beach. In most of these pictures, she’s showing teeth but failing to forge a candid smile. It looks as if she doesn’t know how.

In most of these pictures, she’s showing teeth but failing to forge a candid smile. It looks as if she doesn’t know how.

Then there was Costa Rica. Another slew of unrecognizable photos: brown fuzz (a monkey?) tightroping a phone line, a hazy zigzag (boa constrictor?) nestled in a pile of leaves. But also a set of clear, earnest self-portraits. She’s left her hair undone in them, her perm curly and wild. Wide jungle fronds splay at her shoulders. You can see her giving in to the moment, the soft corners of her mouth upturned. Finally, inside her bungalow, where the peach-painted walls warm her skin and the room, she beams a sincere, toothy smile.

I have nearly identical, unremarkable photos from Costa Rica. Monkeys (hairy blurs) carousing in sky-high vines, an eyelash viper (a cloudy coil) hidden on a tree trunk. I’d flown to Costa Rica on my 29th birthday. A week prior, a patron at work drunkenly spilled a craft beer all over my butt. I caught myself glaring at her, looking positively homicidal. At home, I came unhinged, and howl-wept, pausing between gasps for sips of wine. What was I doing with my life?

On a whim, I decided to escape the States for as long as I could afford (four days). I remember arriving to Costa Rica’s Caribbean coastline at midnight, driving through velvet darkness to my beachside bungalow. I fell asleep to the trill of a million little living things secreted by shadows. I hoped I’d wake up an improved person, bequeathed overnight with instant, magic clarity.

I don’t have pictures of the dismal moments, like when my jungle guide’s feral dog chased me and I fell face-first onto his gravel driveway. Or when the cocoa farmer’s apprentice insulted me in Spanish while toasting my beans. I did relish a few moments of peace, while lying in a hammock outside my bungalow where I took many of my own unsuccessful self-portraits. I returned to New York sun-kissed but, to my dismay, otherwise unaltered.

Real change is neither instant nor magic, but a long process, a kind of honest work. Then one day you reach a point of stillness, when you can look, maybe only briefly, with clear eyes, and simply let go. My mother knows this. She has yelled my name in many far-flung places, at the top of peaks and cliffs, over frozen lakes, or while riding Greek donkeys. I asked her once why she called out our names, and she answered: “Just to say something.”

I understood when I began yelling her name too, first while standing on a towering peak in the Icelandic highlands, then again while perched on the white cliffs near Cochiti Pueblo in New Mexico. It soothed me to see how the terracotta mesas pleated into an opulent skyline, or how miles of slick deltas wove through black sand and vanished into the horizon. I sang and called her name over and over. Can you imagine? Each time I shouted, she echoed back.