A cache of secret documents from former special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and potential attempts by President Donald Trump to obstruct the inquiry was turned over to BuzzFeed News and CNN on Friday in response to Freedom of Information Act lawsuits.

Key Takeaways:

The heavily redacted interview summaries, known within the FBI as 302s, reveal what Trump administration and campaign officials, as well as others close to the president, told investigators about a wide range of issues. In many instances, the witnesses' statements to FBI agents and federal prosecutors were omitted from Mueller’s final report, which was released in April 2019.

Unusual attorney-client conversations

The latest batch of documents shows that during two interviews in late 2017, former White House counsel Don McGahn gave FBI agents mixed signals on Gen. Michael Flynn.

On one hand, McGahn believed that the national security adviser’s “time was up” after lying to Vice President Mike Pence about conversations with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, and that there was “no way Flynn did not know he had talked about sanctions on the calls.”

But McGahn, a critical figure in the Mueller investigation, also recalled a debriefing with Acting Attorney General Sally Yates that made him feel as though Flynn “was not in [redacted] trouble.” McGahn said he asked Yates if the agents had “really pinned him down.” Flynn assured him that the investigation was winding down, according to the FBI summaries.

During a later meeting with the president, McGahn explained the Logan Act, which prohibits unauthorized individuals from negotiating with foreign governments. He also assessed “no clear 1001 violation” — false statements to the FBI — by Flynn. The records are heavily redacted and do not indicate what happened at a subsequent meeting with Yates that McGahn requested.

After Flynn was fired, FBI Director James Comey has previously said the president told him, “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go.” According to the new FBI summaries of McGahn’s interviews, the president denied this to his lawyer — but added that he was “allowed to hope.” Trump did not think he had crossed any lines, McGahn said.

McGahn recalled how the president pressed him to have special counsel Robert Mueller removed and that he was tasked with stopping former Attorney General Jeff Sessions from recusing himself.

The 34 pages of interview summaries show McGahn reflected for agents on other parts of his time in the White House. Early in the administration, McGahn said that he gave the president a primer on how to properly communicate with the Justice Department: Leave it to the White House counsel, McGahn explained.

“Having that framework prevents the White house from ‘nosing in’ on investigations,” McGahn said.

He also recalled speaking to the president about Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort and his role in the Russia investigation. McGahn “sort of talked” with Trump about whether Manafort had any information that was “potentially harmful” to the president.

The rest of this section is redacted, as are many others. Late in one interview, the agents asked McGahn about an obscure message that said, “No comms/serious concerns about obstruction.” McGahn explained that it was his way of expressing concern about the press team saying “crazy things” and that he urged them not to spin it.

On second thought, let's not meet with the Russians

James Jay Carafano, a national security and foreign policy expert at the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation, appeared to bolster former attorney general Jeff Sessions' contention that Sessions pushed back on the suggestion of a Trump-Putin meeting in March 2016.

Carafano recalled that at the meeting, which included Trump and other campaign advisers, George Papadopoulos said he could make a connection between Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Papadopoulos would eventually plead guilty in the Mueller probe to lying to investigators about his efforts to communicate with Russians.

Carafano told investigators that Sessions "voiced his concerns" that such a meeting could violate the Logan Act, which prohibits ordinary citizens from engaging in foreign policy. Sessions testified in Congress in late 2017 that he had forgotten about the meeting and Papadopoulos' offer, but believed he told Papadopoulos he wasn't authorized to represent the campaign with the Russians. Papadopoulos reportedly told a person he met at a Chicago bar in April 2018 that Sessions "encouraged" him at the March 2016 meeting.

Papadopoulos didn't appear to make too much of an impression on Carafano — Carafano recalled "a young man with dark hair" bringing up the Russia connection, and told investigators he didn't know the man "and never saw him again."

Help wanted

On September 13, 2018, FBI agents interviewed a man who told them about the origins of a Delaware non-profit that was created just months before the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting and backed by a group of wealthy Russians. Though the interview summary does not reveal the man’s name, he is identifiable as Robert Arakelian based on his mention of a BuzzFeed reporter who had knocked on his door, as well as other factors.

Robert Arakelian was the listed president of the non-profit, the Human Rights Accountability Global Initiative Foundation. In 2016, the group lobbied US political figures to change the Magnitsky Act, a sanctions law targeting wealthy Russians involved in a $230-million tax fraud.

Angered by the law, the Russian government halted US adoptions of Russian children. The foundation was created with the stated purpose of working to resume the adoptions, but lawmakers have said the group’s focus was largely on Magnitsky.

“There wasn't an indication that this was linked to a Russian government effort,” according to Arakelian’s interview summary, “but they believed that if they could remove the name Magnitsky they could then go to the Russian government which would lift the adoption ban in a quid pro quo scenario.”

In June 2016, two of the foundation’s representatives attended the much-scrutinized meeting at Trump Tower at which senior Trump campaign officials had thought they would receive compromising information on Hillary Clinton. They were frustrated when those two representatives — Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya and Russian-American lobbyist Rinat Akhmetshin — used the opportunity to largely promote the foundation’s cause.

Though Bloomberg, citing unnamed sources, had reported that Mueller was scrutinizing the foundation, the Arakelian interview summary provides the first documentary evidence that the foundation was being probed by the FBI. BuzzFeed News also reported that Mueller had records showing that the foundation’s bank had flagged a half-million dollars in payments from its wealthy backers as suspicious.

Arakelian told FBI agents that Denis Katsyv, a Russian whose company was accused of laundering the proceeds of the Magnitsky fraud, invited him to a meeting to discuss a job. Arakelian told investigators that when he arrived, the participants “were discussing adoption issues” and talking about creating the foundation. Arakelian said the meeting was attended by Katsyv, Veselnitskaya (who worked for Katsyv), Akhmetshin, and a man named Ed Lieberman, a longtime DC attorney and former lobbyist who has worked closely with Akhmetshin, along with a couple of others.

At the end of the meeting, Katsyv offered Arakelian a job, he said, for which he was paid. Though his position is redacted in the interview summary, Arakelian was listed on Delaware state records as the president, treasurer, secretary, and director of the foundation.

Arakelian “believed it sounded more important then [sic] it was,” the summary says. He also appeared to tell the agents that “he was not a decision maker and did not direct anyone.” Rather, it was Akhmetshin who “was the decision maker and told [redacted] who to meet.”

“Akhmetshin and Lieberman worked as lobbyists for HRAGIF,” the interview summary said. The foundation also worked with two DC lobbying firms, Cozen O’Connor and Potomac Square Group, and they “received checks for services.”

Arakelian said “[f]inding money wasn’t [his] job,” and that he “assumed that only Katsyv and Veselnitskaya were doing that.” Meanwhile, Veselnitskaya “was involved in working with Russia on adoption issues,” he said. Veselnitskaya has since been accused of secretly coordinating with the Russian government while defending Katsyv in a Magintsky-related case brought against him.

The foundation was officially created in February 2016, according to Delaware state records, and Arakelian is listed as the incorporator. But Arakelian told the FBI he “was not involved in the incorporation” and that it was actually Lieberman and the law firm BakerHostetler who “conducted” it.

The interview summary also says that Arakelian didn’t find out about the Trump Tower meeting until he heard about it on CNN the next year, further suggesting that he knew very little about the actual workings of the foundation, despite his official titles.

An Egyptian connection?

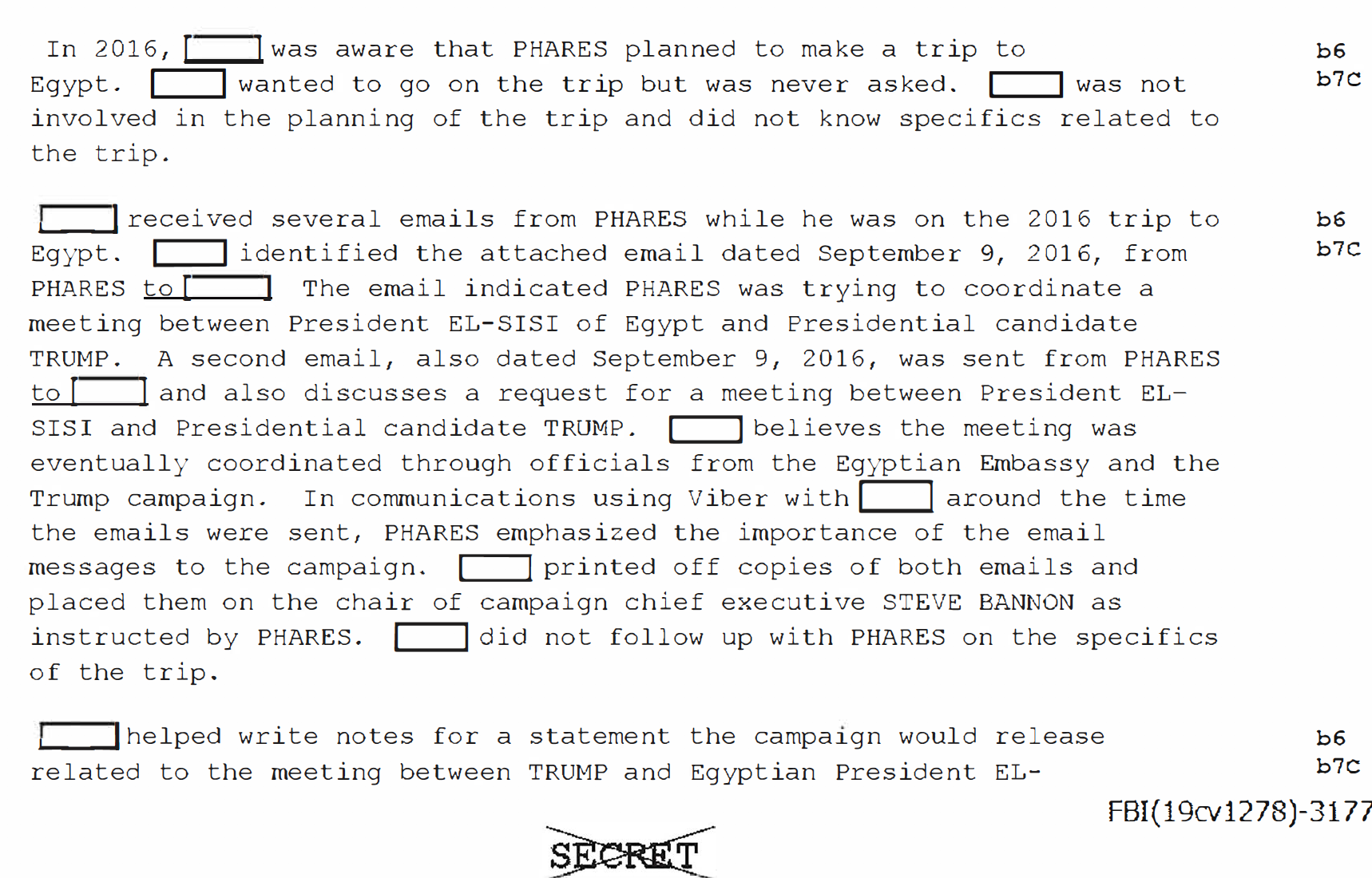

The newest batch of documents shows that on Nov. 20, 2017, agents interviewed an individual whose name is redacted, but who is identified as a female Trump campaign staffer and transition official who went on to work for the National Security Council. The person told investigators she was hired to work for the Trump campaign after Walid Phares, who served on Trump’s foreign policy team, connected her with the campaign. The FBI had investigated whether Phares was secretly working for the Egyptian government to influence the campaign, the New York Times recently reported.

The interview with the unnamed woman shows investigators were interested in what she knew about the connections between Phares and Egypt. The woman told the FBI that she “received several emails from Phares” while he was on a trip to Egypt in 2016, including two emails in September discussing efforts to set up a meeting between then-candidate Trump and Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The two men ended up meeting that month, and the woman believed “the meeting was eventually coordinated through officials from the Egyptian Embassy and the Trump campaign.”

She also said that Phares, using the secure messaging app Viber, “emphasized the importance of the email messages to the campaign” and that she “printed off copies of both emails and placed them on the chair of campaign chief executive STEVE BANNON,” per Phares’ instructions. She also said Phares “may have traveled to the United Arab Emirates around the same time he went to Egypt.” Then, investigators asked the woman about her own contacts with Egyptians, whose names are all redacted. Phares was never charged with a crime.

Someone call the help desk

A witness whose name was not revealed told investigators about strange developments involving Paul Manafort’s laptop. While Manafort was in jail awaiting trial, he was approved to use a laptop in the jail's law library to look at documents related to his case. The administrator account was password-protected so that he couldn't access the internet. According to the witness, however, on Aug. 21, 2018 — the day that the jury found Manafort guilty — the administrator password didn't work. Manafort's lawyers previously had picked up the computer from the jail and then brought it back again, but the witness said they got a note indicating the lawyers hadn't changed the password. It was unclear who had.

The witness also said that someone (that name, too, is redacted) brought two USB drives for Manafort. One of the drives was labeled "Blank." It did not appear to have any files, but when the witness plugged it in, the memory was half full. After reconfiguring the drive, the witness told investigators that they saw a folder called "trash" that "contained a large number of hidden files." The witness didn't open the files and notified the Alexandria sheriff's department. A lawyer for Manafort did not return a request for comment.

Someone call the help desk, part II

Russia's hack of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in 2016, which led to the leak of large caches of emails, may have had more personal consequences for some of the people who worked there, an unidentified DCCC employee told investigators. She said that "many people" had personal income tax returns falsely filed under their names in 2017, and that the DCCC paid for credit monitoring services for employees. The woman said she didn't get any alerts for suspicious credit activity, but described the prospect of having her personal emails released "terrifying." A spokesperson for the DCCC did not return a request for comment.

Russian intelligence was able to hack the DCCC through a tactic known as spear phishing — sending emails crafted to look legitimate but that actually featured a malicious link that would give a hacker access to the person's email account and other information. Presented with printed copies of some of the spear phishing emails sent to the DCCC, the employee told investigators that they were "convincing" and "appeared legit."

The ultimate sin

A heavily redacted December 7, 2017, interview investigators conducted with former communications director Hope Hicks contains additional details about the fallout of the 2016 Trump Tower meeting where Donald Trump, Jr. and other senior campaign officials were offered dirt on Hillary Clinton.

Trump and Trump, Jr. had publicly said the meeting was focused on Russian adoption, leaving out the offer of compromising information on Clinton. Hicks told investigators she told Trump that The New York Times obtained emails that contradicted the president’s account.

“Trump told Hicks not to respond to the story which Hicks thought was odd since Trump usually considered not responding to be the ultimate sin,” Hicks’s interview summary said. “Trump asked Hicks to confirm this meeting was about Russian adoption to which she confirmed that’s what she thought it was about,” the interview summary said. “Trump told her to just respond with the fact it was about Russian adoption.”

The interview summary goes on to say that Trump rejected a statement she had prepared about the meeting, arguing “they were saying too much.”

“Trump told Hicks not to explain so much but just say he took a brief meeting and it was about Russian adoption.”

A fuller picture

Previous installments of the Mueller memos have revealed important new information about the investigation and the events that preceded it. Records released to BuzzFeed News and CNN last year showed that Manafort was still advising the Trump campaign three days before Election Day in 2016 — despite his having been fired as campaign manager nearly three months earlier. That fact, wrote Trump’s next campaign manager, Steve Bannon, in an email, needed to be kept secret or “they are going to try to say the Russians worked with wiki leaks to give this victory to us.”

Rick Gates, Manafort’s longtime business partner who served as deputy campaign chair, told investigators during an April 10, 2018, interview that after it was revealed that the Democratic National Committee’s computer server had been compromised, Manafort began pushing the idea that Ukraine had orchestrated the hack. That unfounded conspiracy theory persisted in right-wing circles long after the US intelligence community concluded Russia was in fact responsible. Indeed, during the July 2019 call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky that eventually prompted Trump's impeachment, he asked Zelensky to help investigate the Ukraine hack theory.

A day after Gates spoke to Mueller’s investigators, Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner was interviewed by the team. He described a meeting he had prior to the election with Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador at the time, who told him: "we like what your candidate is saying. It's refreshing."

“They discussed Syria and having the Russian generals brief” then-national security adviser Michael Flynn, Kushner told the investigators. According to the 33-page interview summary, Kushner asked whether they could create a back-channel line of communication with the Kremlin via the Russian Embassy in Washington. Kislyak waved off that proposal, the records show, and later told another Trump adviser that Kushner “should meet with someone else who was a better channel through which to communicate to Putin.”

A historic document, still emerging

The 448-page Mueller report was the most hotly anticipated prosecutorial document in a generation. But it reflected only a tiny fraction of the primary-source documents that Mueller’s team had amassed over the course of its two-year probe.

In May 2019, BuzzFeed News, and later CNN, filed FOIA lawsuits against the FBI and the Justice Department to gain access to the thousands of pages of interview summaries of the witnesses who spoke to FBI agents and prosecutors. Following an October ruling by a federal judge ordering the release of the documents, the two agencies began turning over the 302s last November. Under the court order, they must disclose records every month, and thus far, the government has released summaries of more than 100 interviews — totaling nearly 2,000 pages — of some of the more than 500 witnesses who spoke to Mueller’s team during the course of the investigation.

The majority of documents released so far under the court order have been heavily redacted, leaving vast swaths of information about the case obscured from view. BuzzFeed News has challenged some of those redactions, arguing in court that one category of exemption that the government has cited to justify the withholdings is legally unfounded, politically motivated, and was implemented solely to protect the president.

Although the Mueller investigation led to 37 indictments and seven convictions, Trump has aggressively sought to discredit it, repeatedly referring to it as a “witch hunt.” His efforts have been supported by Attorney General Bill Barr, who has been accused of intentionally misrepresenting Mueller’s findings and who has taken the highly unusual step of intervening in several cases related to the investigation. Most recently, the Justice Department took the extraordinary step of asking a judge to dismiss charges against Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser, despite the fact that he had voluntarily pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI. Barr claimed in an interview with CBS Evening News earlier this month that the FBI had tried to lay a “perjury trap” for Flynn. Last year, Barr also tapped a US attorney in Connecticut, John Durham, to investigate the origins of the Russia probe.

BuzzFeed News is still pursuing five lawsuits demanding that the government release a huge volume of other records generated by the Mueller investigation, including search warrants, memoranda, talking points, financial records, and legal opinions, as well as any documents that address discussions between Barr and other high-ranking Justice Department officials about the decision not to charge Trump with obstruction.

Lawyers for the DOJ, which opposes the release of those documents, have claimed they could total some 18 billion pages and take centuries to redact and release.