Linh was 16 when she left a life of poverty and violence in Vietnam for England. Just weeks later, she was gang-raped by her traffickers.

The rape came to light only after a British doctor told her she had a sexually transmitted disease. “I was a virgin before I left Vietnam and I am not a virgin anymore” is the only way she could articulate to BuzzFeed News what happened when she became a domestic slave.

When the police arrested her at a Manchester nail salon in September 2017, Linh was relieved — she thought she was finally about to get help. The good news came eight months later: The UK authorities recognised her as a victim of modern slavery.

But days after her 18th birthday, the government that had pledged so loudly to help victims like Linh rejected her asylum claim and informed her that she would be sent back to the country of her traffickers.

“She’s been gang-raped and brutalised, and you’re now saying you’re refusing her right to stay?” her foster father said. “The default is to reject. It is brutal for the children.”

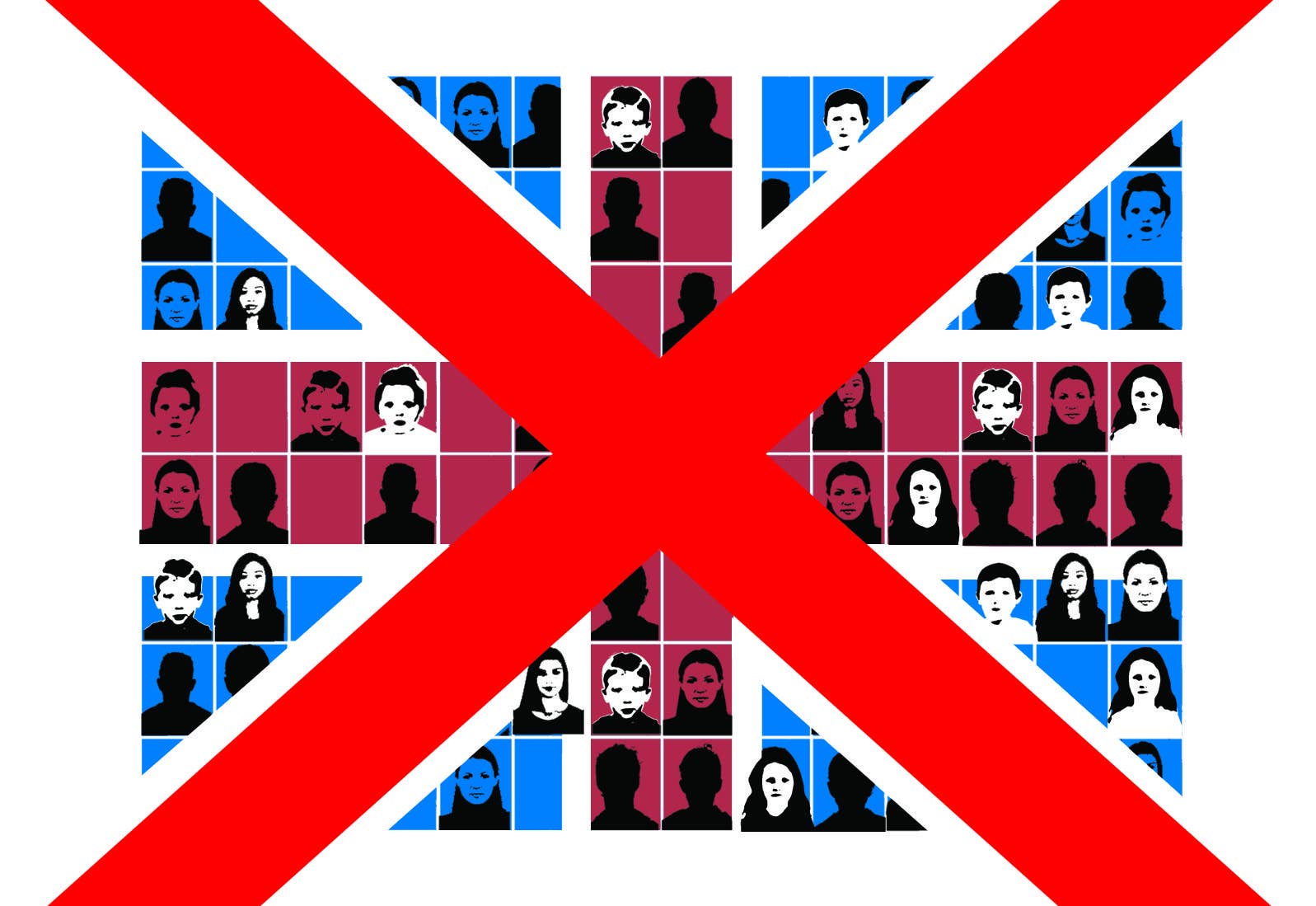

There are hundreds of child trafficking victims like Linh — at risk of deportation and facing the wrath of traffickers in their home countries as a result of the British government’s “hostile” immigration policies.

Figures obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal that the Home Office rejected 310 applications for discretionary leave to remain and 65 asylum claims made by child victims of modern slavery between April 2017 and the end of 2018 — the year the Windrush scandal broke, which led to reversals and embarrassment for the British government.

The freedom of information responses show that the government approved only 16 out of 326 applications made by children officially recognised as modern slavery victims who had requested discretionary leave to remain — an immigration status that can give people a temporary right to stay in the UK if they have suffered extreme hardship. The approval rate for asylum claims was higher, with 136 applications approved out of 201.

The Home Office released the data only after a yearlong battle with BuzzFeed News that involved a formal complaint to the information regulator and multiple internal reviews.

While there is likely to be some overlap in the two sets of figures — victims are able to apply for both discretionary leave to remain and asylum, so they may be counted twice — the new data reveals that an alarming number of children who had fallen prey to traffickers have then been put at risk of removal from a country that is supposed to be a world leader in tackling modern slavery.

The revelations undermine Theresa May's attempts to frame the tackling of modern slavery as a central legacy of her premiership. Last month, she told world leaders they had "a moral duty" to speak up for its victims.

As home secretary, May introduced the Modern Slavery Act, designed to offer better protection to survivors, but major flaws in it meant it did not deliver what it promised. "We are here to help you," May told victims as she unveiled the act. But the new data shows they have come up against a legacy she will be much better remembered for: the hostile environment.

BuzzFeed News asked the Home Office why so many applications from child trafficking victims had been refused despite the government's pledge to help them.

In a statement, the department did not directly address that question or the new data. Instead, a spokesperson said the government was "absolutely committed to ensuring they [victims] get the support they need and we have stringent statutory and policy safeguards in place to protect and promote their welfare".

They continued: “Our world-leading Modern Slavery Act has led to thousands of victims — including children — being protected and hundreds of convictions. But we know there is more to do, which is why we established the independent review of Modern Slavery Act 2015 to ensure that the UK continues to drive the response to modern slavery.”

But independent MP Frank Field, who is currently carrying out that independent review of the act for the government, called BuzzFeed News’ findings “shocking”.

“How is it that one side of the Home Office’s brain is endlessly seeking means to strengthen the Modern Slavery Act, when the other side of that brain is devising ways of deporting children recognised as victims of slavery quite possibly so they can be re-enslaved?” he said. “Stopping this wicked scandal should be the first task of the new home secretary.”

Linh would have been one of the children included in those government statistics — except the Home Office waited more than 12 months until the week after her 18th birthday to reject her asylum application. Her lawyer, Natalia Fulop, believes this was a deliberate tactic.

“I think that they do it so that they’re easier to deport,” Fulop said. “I’ve seen a pattern where the Home Office will wait till right after they’re 18 years old and then reject their application.” Several other trafficking lawyers told BuzzFeed News they too had heard anecdotal evidence of this behaviour.

When the rejection letter arrived in June 2018, Linh was devastated — she feared being killed or retrafficked if she were sent back. “I am afraid to go back to Vietnam because the people who brought me here, because I owe them a lot of money for the travel to the UK,” she said. “Also because I am not a virgin, I am afraid to go back to live in Vietnam. People in my village and everywhere else will judge me for not being a virgin, and I will not be able to live peacefully and have a family.”

Another Vietnamese girl, Phuong — BuzzFeed News agreed not to use the girls’ real names to protect them from their traffickers — was also afraid of being sent back to Vietnam. She was trafficked in the same way, arrested at the same nail bar and taken in by the same foster family as Linh. And like her foster sister, she had her application to stay in the UK rejected by the Home Office too.

“They were distraught when they were refused,” the girls’ foster father told BuzzFeed News. “It was a bombshell. There were floods of tears. … It’s a lot for children to go through.”

In a letter dated March 1, the Home Office rejected Phuong’s requests for asylum or any other kind of leave to remain, stating that it did not believe that the child trafficking victim was at risk of retrafficking back in Vietnam, where her traffickers live and where she had no known family.

“It is not accepted that you will face a risk of persecution or real risk of serious harm on return to Vietnam,” the letter read. “Because it is considered there are services available in Vietnam to support you.”

The Home Office added it had considered whether Phuong should be granted the right to stay because she was an “unaccompanied child who had claimed asylum” but decided she did not because she was “17 1/2 years of age”. The letter warned Phuong that she “must now leave the country” or she may be “detained” or “removed to Vietnam” if she did not appeal the decision.

In her witness statement, Phuong described being terrified at the thought of being deported to the same country as her traffickers. “I often cannot sleep at night when I think about my future, the fear that I will be sent back to Vietnam,” she said. “I sometimes feel it would be easier to die, if I jumped out of the window and kill myself.”

Phuong also told her caseworker that she often had nightmares and flashbacks to her time spent in forced labour.

She was 16 when she was trafficked to Europe from her rural village in Vietnam where she lived with her grandmother. She had dropped out of school when she was 13 to take care of her grandmother who was “old and sick” — Phuong didn’t know if her parents were alive and she had no siblings. She remembered life in their one-room home as “poor and simple”. She sold eggs from their chickens at a nearby market, and they fed themselves from their vegetable patch and her grandmother’s small pension.

So when a woman turned up in their village with the promise of a better life for Phuong abroad, her grandmother agreed. Phuong was put on a plane and told that she was going to study in France, escorted through every airport layover by a different stranger.

But when Phuong arrived in France, there was no school. Instead, she was put to work in what she described as a “drug house” where she spent hours every day looking after “strong-smelling” plants for no pay and sharing a cramped house with other Vietnamese workers. The doors were kept locked and her documents and money taken from her.

Phuong was terrified she was being kept for organ trafficking and so one day she made her escape, slipping through a door her traffickers had forgotten to lock and travelling to the UK in the back of a lorry.

When she arrived in England in September 2017, Phuong walked aimlessly for around two days, “tired, hungry, and cold” and with no choice than to beg for food. It was then, at her most lost, that Phuong happened to walk past the nail bar where Linh was working and spotting another Vietnamese girl, decided to go inside and ask to charge her phone. That was when the police swooped and arrested her, Linh and the other Vietnamese people inside.

Linh and Phuong became close after being placed in the same foster family; so when the first Home Office rejection came, the threat of being separated and sent back to Vietnam was a devastating blow for both girls.

But on Aug. 20, 2018, a court finally overruled the Home Office’s original decision in both cases. The tribunal judge granted Linh asylum after concluding that — contrary to the government’s argument — Linh was highly vulnerable and at “real risk” of retrafficking if she were returned to Vietnam, where “there is a reasonable degree of likelihood that the protection provided will not be adequate or sufficient”.

Almost a year later, on June 19, Phuong was granted “humanitarian protection” on appeal, which gave her the right to stay in the UK for five years. She will then be able to apply for the permanent right to stay in the country she now considers home.

The lawyer for Phuong and Linh believes it should not have taken a court to overturn the Home Office’s original decision in both cases.

“It’s not fair that trafficking victims have to fight so hard for the right to stay,” Fulop said. “It breaks all the obligations the government has to victims of trafficking ... and these are trafficked kids, there is clear evidence of vulnerability.”

But it isn’t only child trafficking victims being affected by the hostile environment. Hundreds more vulnerable adult victims have also been put at risk of deportation after the Home Office denied them the right to stay in the UK.

The freedom of information responses obtained by BuzzFeed News show that over the same 20-month period, 1,281 applications for discretionary leave to remain made by adult victims of modern slavery were rejected by the Home Office, along with 193 asylum applications.

Trafficking victims are caught up in a wider decision-making process that has been proven to be unreliable. More than half of all the Home Office's immigration decisions appealed in court are overturned, its latest figures show. In the year to March, 52% of all immigration and asylum appeals were allowed, with 23,514 people having a decision reversed. Just three years earlier, the rate was 39%.

A young woman BuzzFeed News has agreed to call "Kinga" become one of those trafficking victims when she was a teenager — and her 3-year-old son also ended up at risk of deportation.

Kinga was 19 years old when she moved to London from Poland in 2014 and fell into the hands of her first trafficker, a man she said violently abused her and tried to pimp her out to his friend after she married him.

Kinga’s husband confiscated her passport and sent her out to work 12- to 14-hour shifts in factories. Kinga said that she didn’t see a penny of the £400 a week that was put into her bank account and had never even seen her own debit card.

But the physical violence was the worst. “When I was four months pregnant, he wanted to jump on my belly to make me have a miscarriage,” she told BuzzFeed News. “He threatened me with a knife, there were beatings, and he tried to strangle me.”

Kinga said she finally managed to escape with help from social workers after she was hospitalised following a beating so severe it led to her losing her vision in one eye for a week. She was placed in a women’s shelter soon after her baby was born, but after the support dried up Kinga found herself homeless and back in the hands of a trafficking gang.

Kinga was trafficked three times in total, moved around the UK by slaveholders who exploited her for cheap — more often, free — labour. She worked backbreaking shifts, she said, cleaning offices, houses and caring for elderly relatives of travellers. She slept on filthy mattresses in houses crammed with a dozen workers, and was often beaten by her traffickers.

Yet, when Kinga finally escaped for good in 2018 the Home Office deemed that her circumstances weren’t “compelling” enough to grant her discretionary leave to remain. “I would prefer to hide and live in the country and live poorly rather than go back to Poland,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I don't have anything or anyone to go back to.”

The Home Office rejected Kinga’s application a second time, despite testimony from a support worker that she “remained at risk of harm and retrafficking” unless her leave to remain was granted. Without it, she would remain unable to access any housing assistance, benefits, or even medical support for her anxiety and depression that she had been receiving as a recognised victim of modern slavery.

For Kinga, more than her own future was at stake. Despite her young son being born in the UK, he too was at risk of deportation after the Home Office rejected her immigration application because neither of his parents were British.

But in a letter dated March 2019, the Home Office stated that there was no “realistic risk” of retrafficking if Kinga were “returned” to Poland and that they had seen no information to suggest that her 3-year-old son’s welfare would be “endangered if they were sent back to Poland”.

“It is considered to be in your son's best interests to remain with his primary carer (his mother) within his own cultural background in Poland,” the letter concluded.

It was only thanks to a new Brexit policy — and the support of her lawyer and trafficking charity Hope for Justice — that Kinga and her son were eventually allowed to stay in Britain. In May this year, she was granted the right to remain in the UK permanently through the European settlement scheme, introduced as a result of Brexit, to allow EU nationals who have lived in the UK for at least five years the right to stay.

Kinga now has a “fantastic” job working with the homeless and is preparing to marry her new partner. Linh and Phuong have a loving foster family; they receive counselling and an education. Linh is the top of her class and Phuong wants to become a doctor — opportunities and safety they never had back in Vietnam.

But Carita Thomas, a solicitor at the Anti-Trafficking and Labour Exploitation Unit who represented Kinga, told BuzzFeed News the way the Home Office forced trafficking victims to battle for the right to stay undermined the government’s rhetoric on modern slavery.

"The government can’t hold itself out as a world leader in protecting victims of modern slavery," she said, "when the experience of victims going through the [immigration] process can be worse than their experiences of exploitation."