The year: 2006. You, a college student, lose your mobile phone or otherwise render it unusable in some sort of Natty Light-related incident. Gone are all the contacts you’ve acquired in school since your first days as a freshman. (This was obviously in the days before iCloud or Google Contacts would save you.) But all is not lost: All those fellow students are on a new website called Facebook, and with its Groups feature, you can gather them all in one place to ask them to post their phone numbers. Problem solved.

In a way, this may have been the site’s first meme. Facebook probably didn’t anticipate Groups serving such a one-off, self-centered purpose, but soon this sort of group became a ritual for anyone on Facebook. People would create a group and pass along the story of how they lost their phone. At the same time, they’d often comment on the whole idea of people losing their phone and going on Facebook to desperately ask friends to get their numbers back. They too had joined Facebook’s legions of idiot phone-losers. And they acknowledged it.

It was a different time. When it was just a place for college students, everything on Facebook felt like it was taking place inside a fortress. You had to have a college .edu e-mail address to get in, and everyone inside of it were peers: people of the same age, going through the same things, still students yet to fully enter adult life. There were no parents, potential employers, or spammers looking in on what you were doing. It was an inclusive, intimate community. There were actually very good reasons to feel safe posting your phone number publicly and see it as a small step towards a new interconnectedness.

Today, most people no longer feel comfortable posting their number in public on Facebook or asking their friends to do so. According to a poll last week, most of the site’s users trust Facebook “only a little” or “not at all.”

Of course, old Facebook still exists on Facebook proper. But the walls have come down and everything we did in the early days of the site has been exposed. Even though the social network eventually abandoned Groups — small, often rather inactive groupings of people centered around campus clubs or inside jokes — in favor of Pages, which have more of a professional appearance appreciated by public figures and businesses looking to have a public face on the social network, inactive groups were archived. Their membership, except for the group creator, was expunged. What remains in the backwaters of Facebook is a huge graveyard of hollowed out, vacant groups littered with posts left there half a decade ago or more by pioneer users. Overnight, the famed “One Million Strong for Barack” Facebook group from the 2008 election was depleted of its titular user base.

What this means for lost-phone groups is that at least many thousands of phone numbers are sitting out there in abandoned Facebook groups, attached to the full identifying information of each number’s owner.

I get scam phone calls and text-message spam myself every week, and I have to wonder if it’s because my number is listed somewhere in the lost-phone-group crypt. Unfortunately, there’s really no way of knowing. I can no longer see groups I was a member of five or six years ago, unless it’s a group I created. The “archive” process removed me from any of the lingering lost-phone groups I belonged to once.

Two years ago, London developer Tom Scott made a Web app called This is Evil to draw attention to this glaring privacy issue. Using Facebook’s API, the app combed the social network for public “lost phone” groups and displayed users and their phone numbers, drawn from groups at random. It was a startling visualization of the depth of personal information once put on the most open areas of Facebook.

Scott told me Facebook’s API has changed and the Evil app no longer works, so he’ll retire it soon. He may not have been able to get Facebook users to go back into old lost-phone groups and delete their numbers, but he praised Facebook’s new default for groups—they’re closed, not open for all to see.

But for users who posted their number years ago in an open lost-phone group, their contact details are still out there in the Facebook graveyard, waiting to be harvested by nefarious individuals like text-message scammers and spammers. People like me, I guess.

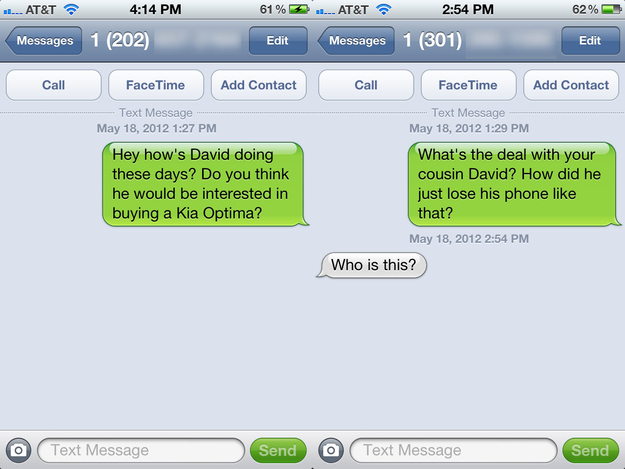

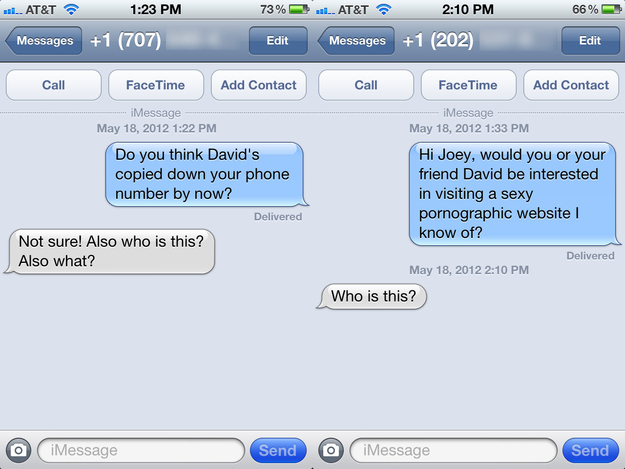

I went to a lost-phone group from February of 2007 and texted the people whose numbers were posted there to illustrate this article. Half a decade later, they didn’t seem to be too pleased about the nuisance.

People just don’t trust the social network like they once did, and there’s perhaps no greater illustration of that than the death of the lost-phone-group meme. Sure, we’re no longer on our first or second cell phone and many have learned to back up their phone contacts. But people still lose their contacts.

These days when you search “lost phone” on Facebook, you’re hit with a deluge of inane, non-interactive pages like “Join if you ever lost your phone, tried to ring it, but its on silent :D” and “I'd Be Lost Without My Mobile Phone.” It’s only when you click over to the anachronistic-looking Groups button do you suddenly become a Facebook archaeologist, confronted with the charred, personal-information-littered remains of how the site was once used.

Facebook’s valuation has skyrocketed the past few years, but I would venture to say it had to have been worth more to an advertiser in those early days, and not just because college-age people are such an important demographic to the industry. Back then, users felt freer to post personal information, thoughts, and drunken photos. People could be real. There was no nagging reminder in the back of their minds that everything they did was on public display. Their school’s network was an actual community. Marketers today would love to have access to a smaller, targeted community like that.

Perhaps one day there will be another social network as trusted, community-centered, and utilitarian for human interaction as Facebook once was. Until then, we have Facebook.

And disquieting thoughts about what we once told it.