In many ways, it’s been an amazing year for Dev Patel: He just won a BAFTA for his performance in Lion, he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor, and his new look has been turning heads across the internet (and in Vogue editorials). He’s landed flattering features in GQ and the New York Times, and seems to be finally earning respect as a “serious” actor — no longer just that charming, awkward kid from Slumdog Millionaire.

But it’s been nine years since Patel was introduced to the international film community through Danny Boyle’s Oscar-winning film, and it’s taken that long for him to find a place in mainstream Hollywood conversation again. Though he’s appeared in notable pictures since, Patel has not been the central protagonist of a wide-release film since 2008. And even now, it’s not a given that he’ll remain on the industry’s radar for very long.

That’s because to be a leading man in Hollywood requires more than just box office success, an award-winning list of credits, or even the esteem of your peers. You also (still) need to embody the American film industry’s narrow ideals of romantic masculinity. With his role in Lion, Patel is no doubt moving in that direction. But Hollywood’s notion of desirability is still firmly rooted in whiteness and limiting ideas of gender. It remains to be seen if he’ll be offered more parts that let him claim certified (and highly paid) Actor in a Leading Role status — and whether the kind of masculinity required to claim it is something worth aspiring to at all.

Ryan Gosling, who is nominated for Best Actor at the Oscars this year, is perhaps the perfect representation of what a modern leading man “should” look like. Ever since his days at the Mickey Mouse Club, Gosling has been cast as a kind of goofy heartthrob. And as Bim Adewunmi points out, his “weird boy next door” persona has only ever served to increase his allure. But whether starring in romantic films like La La Land and Crazy, Stupid, Love, or violent ones like Drive and Gangster Squad, Gosling has also moved fluidly in and out of hypermasculinity. His characters may be more sensitive than other men, but he’s still usually the toughest guy in the room — and he almost always has power over women. In this way Gosling’s performance of manhood isn’t too far from the classic mold developed by the likes of Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando, white men whose ability to show some emotion didn’t preclude them from becoming macho heroes.

Meanwhile, ever since Patel began his career playing a clumsy teenager on the British TV show Skins, none of the “eccentric guy” roles he’s been given — including blogger Neal Sampat on HBO’s The Newsroom, an overexcited hotel manager in the Exotic Marigold Hotel films, and a math prodigy “discovered” by a British man in last year’s The Man Who Knew Infinity — have involved any hint of that dominant, heartthrob framing.

Patel’s trajectory is noticeably different from that of fellow Oscar nominee Andrew Garfield, who broke out around the same time, and who also started off as an inelegant teenage boy on a British TV show (2005’s Sugar Rush). Garfield has a significantly more visible and varied presence in mainstream film today, moving from The Social Network to The Amazing Spider-Man and two different Oscar-nominated films (Hacksaw Ridge and Silence) in 2016. Patel’s Skins co-star Nicholas Hoult has also been able to leverage his oddball performance of masculinity into multiple starring roles since the show ended, including the romantic lead in Warm Bodies and a sensitive superhero in X-Men: First Class. Both have easily made the jump from smaller films into big, lucrative comic book franchises; no such luck for Patel. But surely individual recognition at the Oscars, the most prestigious of film awards, could change his prospects moving forward?

Generations of straight white men have helped create a cultural standard for romantic manhood centered around themselves.

Maybe. But Patel still isn’t white. It’s been 10 years since a man of color last won Best Supporting Actor at the Oscars (Javier Bardem, for No Country for Old Men), and the last to be nominated in the category — Barkhad Abdi for Captain Phillips in 2013 — hasn’t exactly been swimming in opportunities since. Djimon Hounsou, who is black, has been acting since the ‘90s and has two Best Supporting Actor Oscar nominations to his name, for In America (2002) and Blood Diamond (2006), but the young and nomination-less Hoult has already surpassed him in terms of major starring roles.

This isn’t just because the industry itself is still run by white men, but also because generations of straight white men have helped create a cultural standard for romantic manhood centered around themselves. Thus audiences, writers, and even directors learn to associate “leading man” with a particular look and expression of masculinity. And no matter how much attention his new haircut gets, Dev Patel still doesn’t look like that.

Gosling, Garfield, and Hoult have almost never had to play a character who was explicitly described as “white” on screen. The ethnicity and race of the heroes they play is rarely a factor in the larger story, even if it’s always apparent. Meanwhile, not only is Patel visibly a man of color, but he’s also usually cast to play people whose identities are specifically related to their Indian-ness. And when he does get a role that doesn’t constantly draw attention to his skin color, like Alex in the 2014 indie The Road Within, he’s not typically rewarded for it.

Patel has said he enjoyed making Lion because the part of Saroo Brierley, an Indian boy adopted by a white woman (Nicole Kidman) and raised in Australia, was “a character that didn’t require [him] to play into a specific box.” But looking at some of the similarities between his breakout role in Slumdog Millionaire and his character in Lion, it’s not clear that Academy voters aren’t just building that box around him anyway. Like Hounsou and Abdi, Patel is still to some extent relegated to the part of “dark-skinned foreigner,” which keeps him a safe distance from white Hollywood’s romantic ideal.

South Asian men, like Asian men in general, are often particularly stereotyped as peculiar when it comes to their sexuality. This typically looks like straight characters who have pent up or overwhelming sexual desire — like Kal Penn’s repressed “Taj Badalandabad” character in Van Wilder — but who express it in ways that are cute, lovably misogynistic, or downright creepy. In an especially horrific episode of The Big Bang Theory, for instance, when Penny (Kaley Cuoco) can’t recall whether or not she and Raj (Kunal Nayyar) had sex the night before, when she was drunk, she exclaims, “Oh God, did you pull some weird Indian crap on me?” (Cue the laugh track.)

This framing of South Asian masculinity is very different from the dominant narrative around straight white men, whose misogyny can be part of their attractiveness, or is often meant to be “sexy.” See: Ryan Reynolds in Van Wilder, John Bennett in Ted, or pretty much every incarnation of James Bond. (Coincidentally, or maybe not, the actor who may have helped popularize the portrayal of sexually frustrated South Asian men in the West — Peter Sellers as the bumbling Hrundi V. Bakshi in The Party — was himself white.)

Despite all this, Patel has some advantages in white Hollywood that actors like Hounsou and Abdi do not: He’s younger, he doesn’t face anti-black racism, and he’s been given an opportunity to squeeze himself into some version of the industry’s leading man mold. Director Garth Davis asked Patel to bulk up for Lion, and as the actor himself describes it, he had to become “a bit more alpha” to play Saroo. It’s hard to miss Patel’s new look in the film, as there’s more than one shot where the camera captures him in bed with his white girlfriend (Rooney Mara), his hair beautifully strewn across a pillow.

It’s not only a physical transformation that suggests a “more masculine” Patel, but also the way Saroo’s character is written. He spends much of the film pensively staring at a computer screen or expressing frustration at not being able to find the answers he knows are out there. And that furrowed brow of seriousness is a hallmark of the award-winning “leading man,” whether it’s the troubled Russell Crowe in Gladiator or the troubled Russell Crowe in A Beautiful Mind. These are men who know something that no one else does, and can’t be bothered to explain it — especially not to women. While Lion avoids going too far down this road, its success does seem to suggest that in order for Patel to continue to find major work in Hollywood, he may be required to further embrace that limited vision of masculinity.

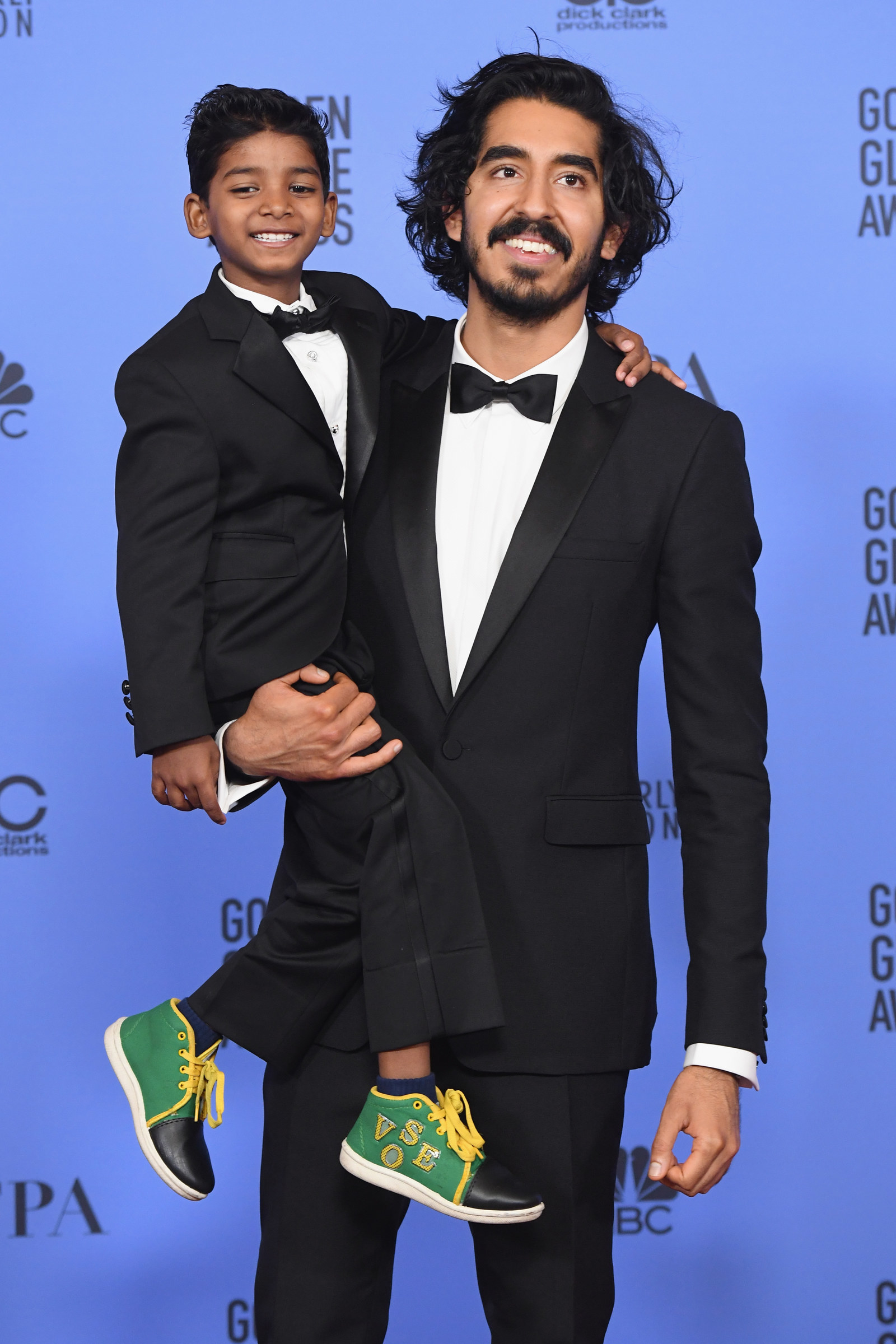

A more promising sign for Patel, on the journey to becoming a romantic lead in the industry, is that his work (past and present) is garnering a growing club of admirers online. And they, for the most part, love him just the way he is. Men and women, including many women of color, are celebrating Patel’s good looks on social media (along with fellow Oscar nominee Mahershala Ali's) particularly as he’s made a series of dapper red carpet appearances throughout awards season, and especially when accompanied by his impossibly cute Lion co-star Sunny Pawar.

As Sulagna Misra has pointed out at The Cut, the sensation of “internet boyfriends” — the phenomenon of people, often women, inventing “shared fantasies” about famous men — is a direct response to the lack of depth and diversity in Hollywood’s portrayal of masculinity:

It’s crucial that these actors are rarely in romantic movies — or at least, not known for their romantic roles. Instead of being presented to us with boyfriend narratives built in ("Here is a sexy, tormented vampire for you to love"), they offer enough of a blank slate that users can write their own forms of romance onto them.

In Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin says that black actors of the '50s and '60s, like Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, were “up against the infantile, furtive sexuality of this country,” and so as a result, Hollywood could not admit that they were the sex symbols they so clearly were. (As in those days, Patel does not actually ever kiss Mara in Lion.) If Poitier and Belafonte were young men onscreen today, they would no doubt have countless fanfics, Tumblrs, and memes dedicated to their beauty, too. This is no small change in the media world, since for over a century Hollywood studios and corporate advertising have dictated how the majority of people are taught to make associations between masculinity, desire, and power. While a single tweet doesn’t have near the reach of a wide-release film, the collective power of people of color online to transform how we talk about film is substantial.

Unfortunately, it may take more than widely acknowledged sex appeal to change how Hollywood spends its money. As Baldwin points out, it’s not as if white people didn’t know that Belafonte was a babe in the 1950s (in fact, myths about the hypersexuality of black men were and are still simultaneously used against them in the industry). And consider how much more difficult it has been for a woman of color like Freida Pinto to break out than it’s been for her Slumdog Millionaire co-star. Despite her Maxim-approved allure, and appearing in that Oscar-winning hit, Pinto has had an even smaller presence in Hollywood than Patel. All the fanfic in the world won’t necessarily convince the white people behind Bond that Idris Elba is “right” for that part, either.

Film and media teach us not only how to think about human relationships, but how to visualize them. As long as the leading man looks mostly like Bradley Cooper or Ryan Gosling — and straight cisgender men continue to be at the center of our moviegoing experiences, overall — those are the same people who will continue to be granted the most power, and love, in the real world too. But seeing a wider array of men portrayed as attractive onscreen can expand our imaginations about others, and about ourselves. Actors of color, just by virtue of appearing in movies, can challenge Hollywood’s narrow vision of desirability.

Is it progress if we’re just re-creating hierarchies of masculinity with South Asian men at the top?

This begs the question: Do we really want Dev Patel to become a classic leading man anyway? In other words, would it be enough for Riz Ahmed to be cast as the next James Bond if Bond is still a man who uses violence to express his emotions? Do we want Patel to be the next Bradley Cooper if it means mostly playing characters who are subtly or clearly dominant over women? Is it progress if we’re just re-creating hierarchies of masculinity with South Asian men at the top?

It’s significant that Denzel Washington was nominated for Best Actor this year — breaking a two-year streak of complete whiteness at the Oscars — but because Fences is a kind of critique of masculinity, his performance itself doesn’t stray too far from traditional representations of it. And it’s especially hard to get excited when we look at the rest of this year’s nominees in the leading category, like Viggo Mortensen’s gentle-but-rugged white patriarch in Captain Fantastic or Casey Affleck’s emotionally stunted turn in Manchester by the Sea. The Academy still seems to be clinging to very narrow ideas about what it means to be a man.

Ultimately the leading man trope, and the industry’s tightly restricted access to it, is a symptom of larger systemic issues. Fixing it requires hiring screenwriters, directors, and producers of color, of all genders, who are willing to challenge the status quo. We might start, though, by looking at those performances that do complicate masculinity a bit, like Mahershala Ali’s compassionate mentor role in Moonlight, and create new models of leadership that aren’t so dependent on existing norms. Young people on the internet, especially women of color, are long past ready for this evolution. But it’s still an open question whether Hollywood is paying attention.

Imran Siddiquee is a writer and filmmaker based in Philadelphia.