In Chicago on a Monday in mid-May, David Blanchard is running late. He’s rushing to a WGN radio interview to promote Ferris Fest, the ambitious event he’s throwing that weekend to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Blanchard, 56, has platinum hair and is wearing black thick-framed glasses and a gray SAVE FERRIS T-shirt.

He is not nearly as unflappable as Ferris. The interview's supposed to be at 9 p.m., but at 8:55, he still hasn’t found a place to park. He lives in Los Angeles, where he worked as a movie trailer editor for 13 years, and he and his wife, Rebecca Sanchez, had gotten lost on Chicago's multi-level streets. When Sanchez finally pulls into a garage, the attendant there, a chill guy named Endale, tells them it’s not the right building for the radio station. “Don’t panic,” he says. “When you panic, you don’t do anything.”

At its most basic, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is about a high school kid who skips school and doesn’t get caught. But that pretty simple plotline — supposedly John Hughes wrote the script in less than a week — isn’t what’s made it beloved for 30 years. Rather, it’s the spirit of Ferris, so perfectly embodied by a then-23-year-old Matthew Broderick, as someone who knows how to really appreciate life that’s resonated. “Life moves pretty fast,” he says at both the beginning and end of the movie. “If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

In truth, though, most of us probably live more like Cameron, Ferris’s best friend who frets and limits himself most of the time. “Pardon my French,” Ferris says, “but Cameron is so tight that if you stuck a lump of coal up his ass, in two weeks you'd have a diamond.”

By 8:58 by Endale is escorting Blanchard up the escalator, through the building, and over the plaza to the entrance of the Tribune Tower on Michigan Avenue, where WGN is. He checks in at the front desk, red-faced and sweating, and checks back with the security guard 30 seconds later to make sure WGN knows he's there.

"I told them," the guard responds.

WGN host Justin Kaufmann appears seconds later, untroubled by Blanchard's lateness, but bothered by something else. "You're not a Chicagoan?" he says soon after they sit down in the studio. "I thought you were a Chicagoan this whole time." He repeats the question moments later on air.

"I've been to Chicago a lot," Blanchard says.

"The only reason I'm surprised about it is Ferris Bueller means so much to Chicagoans," Kaufmann says. "It was shot here. It's John Hughes. Everything about it is very Chicago. It's in our blood. And for someone who's not from Chicago to organize Ferris Fest, that's something. I would have assumed this was a Chicago project."

"We're not a big company. We're just fans. We had to come here and we had to do it."

"Well, we're doing it," Blanchard says. "We're not a big company or a big corporation or anything. We're not even connected with the city of Chicago planners. We're just fans. We're so super passionate about it. We had to come here and we had to do it."

When Blanchard conceived of Ferris Fest, he thought of it as a small bus tour with a few friends to spots around Chicagoland that were in the movie — a repeat of a trip he took with Sanchez in 2008. But when he decided see if any other fans wanted to come and sent a press release to 1,000 news outlets in February, it got more attention than Blanchard anticipated. In a few weeks, Ferris Fest sold over 320 three-day tickets at $300 each and secured a licensing deal with Paramount Pictures as well as support from brands like Hulu and Virgin Hotels. The event was written up from the Chicago Tribune to the New York Times, with Blanchard pledging to donate some proceeds to anti-bullying organizations.

What Blanchard and his small team are attempting this weekend, in a city they’re not all that familiar with, is one hell of a high-wire act: They’ve scheduled a bus tour with six coach buses each carrying around 50 people to the film’s most famous locations. They’ve signed on impersonators for Ferris, Cameron, and Sloane, who’ll re-enact scenes all along the bus tour, plus some memorable actors from the film, if not the ones most people would pay to see. They’re re-creating Ferris’s bedroom — down to the fake snores — in a Chicago hotel. Perhaps most daunting of all, as a grand finale, they’re restaging the downtown parade that Ferris hijacks to perform Wayne Newton’s version of “Danke Schoen” and the Beatles' version of “Twist and Shout.”

To get as many people as possible to attend, they’ve created options besides the $300 all-weekend passes: 1,500 people bought $10 tickets to see Ferris’s bedroom and the parade. Others spent $50 to attend the kickoff ’80s dance, $25 to watch a screening followed by a Q&A with the cast, or $175 for a one-day bus tour.

And at this point, as he stands outside the studio texting his wife, it seems unlikely Blanchard and co. can pull this off. A group of fans who dearly love Ferris, but who have never planned anything on this scale before and don’t live in Chicago, are trying to re-create the film over three days in 10 locations, with the entire city watching. It's a bold proposition. But as Ferris tells Cameron: "Only the meek get pinched. The bold survive."

The Lockport Township High School marching band, who’d performed in the original film, dropped out three days before rehearsal. Lockport, the South Shore Drill Team — who were also in the original movie — the girls who will dance on the float, and the impersonators had scheduled an all-day practice the Sunday before the fest, until Blanchard found himself without a band. “It's been phone call city,” he had told me four days earlier from Los Angeles. “They were in the movie and that was a big point, and now it’s like, ‘Ugh.’”

Blanchard’s set on bringing in players from the original whenever possible, even if it makes more work for him. His goal is to immerse attendees in what Cameron calls “the best day of my life,” with as many references and nods to the film as possible.

Ferris Fest is far from the first of its kind. Lebowski Fest started out as scrappy bowling alley party in Louisville with diehards dressed in character and drinking White Russians. Today it’s approaching its 15th anniversary and has been held in New York, Los Angeles, Austin, and Seattle. Blanchard saw Ferris Bueller's Day Off four times in the theater in 1986, but this is not really about his own fandom or obsession — although quitting your job in your mid-50s to start a business for which you have little training is a bigger homage to Ferris Bueller's spirit than any cosplay ever could be. Using Ferris Fest as a springboard, he is building a company called “Filmed Here” to put on similar re-creations. He’s thinking about hosting a bigger John Hughes festival next.

But for today, he’s focused on Ferris, canceling the rehearsal and scrambling to find a new band. “There’s no time to practice with them now,” he says from L.A., so “I’m just going to gather them around a table with some cars to show them how this is going to go.”

There is some good news: The float company, ABC Parade Floats, is letting the dancers and impersonators practice in its warehouse, so Blanchard no longer has to pay $1,000 to get the float to the practice field. Ferris Fest has a few sponsors, but for the most part, “the ticket sales are paying for putting this on,” Blanchard says. “We have a certain budget we need to stick to.” He declined to disclose the fest’s total budget, saying he’d prefer to keep it private.

So on Tuesday at 4 p.m., six high school girls in German dance costumes, a guy in an animal-print vest, another in a Gordie Howe Red Wings jersey, and a girl in a suede fringe jacket are all in a cramped, cold float factory on Chicago’s South Side.

The six fräuleins are dressed in low-cut lace shirts with tight sleeves, corsets, floral skirts with white aprons, white knee-highs, and loosely tied ribbon chokers. They’re moving around the lower tier of the float, running through the “Twist and Shout” number. The choreographer, Lee Ann Marie, a tiny blonde in wedge-heel boots, has done this routine before: She danced on the float with Broderick in the movie. As she puts the girls through their paces, she bounces and mouths the words to the songs. “It pains me not to do it," she says.

The Ferris mobile has been pulled out from the back of the warehouse, where ABC has 26 other floats in progress, but space is still tight. When the dancers leap, their heads graze the hanging florescent bulbs. After their hops cause the float to rebound violently, Blanchard jokes, “Yes, we have insurance.”

After the run-through, Marie says, "Who had a problem?"

All six girls raise their hands.

"Oh, everyone had a problem,” she says. “Let's go through them one by one."

The float was a major expense at $4,500, but it’s a stellar replica. It should be: ABC Floats built the original. The new one’s a little shorter and narrower, but the key decorations are there. It’s covered in fake grass, and outlined with pink and purple flowers in the front, short evergreen trees near the back, and American flags at both ends. Later, they will add a Hulu banner to its front.

Hank Fiene, who’s standing near the back of the warehouse, helped build the original, but, unlike Marie, he isn’t feeling nostalgic. This is the fourth Ferris float he’s done — another one was for Virgin when it opened its Chicago hotel (Richard Branson rode on top). “It’s a job,” he says.

The plan is for ABC Floats' Thomas Neary to drive the float in the parade. He’s in his forties, but he’s never seen the movie. "When we did the Virgin launch,” he says, “I watched a little because I wanted to see what they'd be doing on top of me, but I haven't seen it and I'm not going to watch it."

Where exactly Neary is supposed to drive the float is a secret — for now. The original parade went down Dearborn Street, but for logistical reasons this one isn’t going to. Attendees won’t be emailed the location until a few hours before the event. This is the idea Blanchard and the city came up with to control the crowd and prevent freeloaders from camping out in the best seats. “That's sort of the plan, to make it so that it's not a huge mob scene, and to give people the opportunity and the time to get there,” Blanchard says.

Of course, that plan doesn’t account for annoyed ticket holders, or curious passersby, or someone spilling the address early. It’s about 8:30 p.m., and the ABC Floats guys have opened a bottle of red. Marie is giving the fräuleins their final instructions: tasteful eye makeup, push-up bras. She says she'll let them know where to get dropped off for the parade Sunday as soon as she can.

"You mean, you don't know where it's going to be?" one of the fräuleins asks.

"No, no one does," Marie says.

Neary is listening. "It's at Daley Plaza," he says. "Everyone knows that."

"No, no they don't," Blanchard jumps in hurriedly.

Marie tells the girls not to tell anyone what they just heard. “Pretend you’re working for a magician,” she — a former assistant to David Copperfield — says, “because magicians don't like when you say any of their secrets.”

Sloane and Cameron are on Dearborn Street in downtown Chicago, where the Von Steuben German Day parade is passing by. They’re looking for Ferris, who has disappeared.

“Cameron, he didn’t ditch us or anything. He’s here,” she says, as they search.

“For all we know, he went back to school,” he says.

“He would not go back to school,” Sloane says.

“Yeah, he’d do it. He’d do it just to make me sweat. Makes me mad,” Cameron says.

Blanchard was supposed to be in Ferris’s bedroom three hours ago, but no one can find him. The room has to be ready for media previews in less than 12 hours, but there’s almost nothing inside. The designer, Sarah Keenlyside, is MIA too.

The movie set's bedroom was on a soundstage, but this re-creation is being built in the private dining area of the downtown Virgin Hotel, a space called The Casting Room that has curtain-covered walls, velvet chairs, and vintage gold stage lights. Currently it still looks more like a swanky lounge than a teen boy’s haven. Only the four fake walls, inset with two doors and three Venetian-blind-covered windows, are up. There’s an unopened Ikea Fjellse twin bed frame on the floor and three boxes labeled “Ferris” (one of them contains a dartboard and a tennis racket).

When Keenlyside arrives at 9:30, it turns out she had to make an emergency run to the nearest Ikea, 40 minutes away. It’s her second trip today. She and Blanchard’s team went earlier, but forgot the wall unit they need for Ferris’s TV and stereo. “I thought I'd delegated someone to grab it, but they didn't,” she says. Keenlyside, who’s an artist and filmmaker, is easygoing, wearing a rainbow scarf, black printed leggings, and sneakers. She’s dreading putting together the Ikea furniture, but is undaunted by how late it is and how much work she still has to do. “I've done it before,” she says. “If I have to stay up till 6 a.m., I will. I've got a couple of Red Bulls.”

She shipped most of Ferris’s stuff from Toronto, where she lives and first re-created the room in an experimental art show called Come Up to My Room. A mutual friend introduced her to Blanchard.

Joe Cruz, of Lincoln, Nebraska, dressed from head to toe as Ferris Bueller.

Not everything is authentic — Ferris’s parents didn’t shop at Ikea — but “the things that bring out the nostalgia factor are there,” Keenlyside says. Up in her hotel room, she has an IBM 5150 (it displays Ferris’s report card, programmed in green type, showing his missing nine days), a broken E-mu Emulator II keyboard (fixing it so she could have programmed in Ferris’s death coughs would have cost thousands), and a mannequin to tuck in the bed (like in the movie, it will be on a pulley system so it moves when the door opens). And of course, there’s a snore track.

She had Ferris’s original TV, but it broke so she’s planning to buy one that’s close enough on Craigslist in the morning (she has the MTV station IDs shown in the beginning of the movie prerecorded). “That's the nail-biter right now,” she says. “That's the cliffhanger. I'm like, ‘Jeez, am I going to get this TV?’”

The room is still empty, so Keenlyside starts searching for Blanchard, who’s supposed to help her put together the furniture. She even calls the documentarian she’d been traveling with to see if Blanchard is with him. Finally Blanchard appears, looking dazed and exhausted. He’s ready to help but first he has to call the guy who’s bringing up a replica of Cameron’s dad’s 1961 Ferrari. He tries to be enthusiastic. "Can’t wait to see your Ferrari!" he says before hanging up.

“It’s hard to say what happened in the last four hours,” he says wearily. “There’s a lot of balls in the air."

Blanchard’s feeling more confident tonight, waiting on Wabash Avenue in front of the Virgin Hotel to greet the actors he’s enlisted for the fest. “I’m having fun again,” he says. “Yesterday was not fun.”

All of the actors have traveled together from Los Angeles on the festival’s dime. Anyone on that morning’s Virgin Flight 232 from LAX to O’Hare would have seen iconic Ferris characters in first class: Edie McClurg (Grace the secretary), Lyman Ward (Ferris’s dad), Cindy Pickett (Ferris’s mom), Jonathan Schmock (the snotty maître d'), and Larry “Flash” Jenkins (a garage attendant who steals the Ferrari).

No one recognized them on the plane, but at the baggage claim Jose Taveras, 27, who’d come to Ferris Fest from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, saw them and bugged out. “I thought, What an amazing thing," Ward says. “It's humbling that someone would come that far and be that enthusiastic.”

Everyone walks through the hotel restaurant and into the re-creation of Ferris’s room, where Keenlyside — despite having been up till 5 a.m. — is still taping up some black-and-white shots of Buddy Holly. The cast is delighted; Ward and Schmock take pictures with their phones.

“Oh my goodness,” McClurg says. “It even has the snores.” She giggles then, the same delightful laugh that made Grace the secretary memorable.

They fill two booths for dinner, laughing and drinking. “Sit down,” Pickett says to everyone. “We’re a family.” They all give credit to Blanchard for getting them there. “He called my manager,” Schmock says. “I said, ‘I'm down if this guy's legit.’" They’re also being paid a small stipend.

To everyone’s disappointment, none of the film’s major stars — Broderick, Alan Ruck, Mia Sara, or Jennifer Grey, who played Ferris’s pissed-off sister, Jeanie — are coming. “I don't get it,” Pickett says. “None of us gets why the leads aren't here.” Blanchard contacted all of them. Ruck said he couldn’t make it, though he was in Chicago, appearing on Good Morning America at the top of Willis Tower. Grey never responded, and Sara and Broderick politely declined.

"If he's gonna fail, he's gonna fail big, and that's the only way to go.”

“I wish Matthew had done more,” Ward says. “I think you count your blessings and say it's part of your career.” (Blanchard didn’t reach out to either Charlie Sheen or Jeffrey Jones, who played principal Ed Rooney and was later convicted of child pornography and related charges.)

All present are overjoyed both to have been cast in Ferris and to have returned to Chicago — some of them haven’t been back at all in the 30 years since they shot the film there. “People recognize me from this one all of the time and I was only in three scenes,” says Jenkins.

Ward and Pickett fell in love on set; they were married for several years and have two children, one of whom is tagging along this weekend. “When my son was 8 or 9, he said, ‘Why didn't you name me Ferris?’” says Pickett, who used to go dancing with Sara and Grey on nights off during filming. Hughes never danced but “loved watching us,” she says. “He loved young people. He’d have to fall in love with you to cast you.”

McClurg doesn’t mind being known as Grace the secretary — and for trilling that “righteous dude” line — for eternity. “I was hoping it would go on forever and it is,” she says.

They’re staying in Lake Forest, where screenings of the film are being held at the John & Nancy Hughes Theater, established for the couple in 2014 (Nancy will attend the Saturday night screening). Blanchard stands in the middle of them, watching his re-creation come together and looking calm. “I don't know if David will pull it off,” Ward says. “But he's doing an amazing job so far. They're working so hard, and just to attempt this is an amazing feat. If he's gonna fail, he's gonna fail big, and that's the only way to go.”

Blanchard starts his welcome speech and thanks everyone for coming. “When I was sitting in front of my computer at the end of last year, I thought, Why is no one doing anything to acknowledge the major milestone of this film?” he says. “I felt the need to take it upon myself to make that happen.” But he seems nervous, rambling on. He thanks everyone again for being here and reiterates that they don’t have a big budget for Ferris Fest, that it was something he just dreamed up in front of his computer one day.

The costumed crowd around him seems antsy. Many have come dressed as Ferris, Cameron, or Sloane. One couple are dressed — flawlessly — as Jeanie and Sheen’s “boy in police station.” They’ve been mingling with McClurg, Ward, Pickett, Schmock, and Jenkins, and posing in the Ferrari replica. "I didn't know if it was going to be like Comic-Con or Hunger Games or vampire stuff,” says Jeff Howard, 38, who’s come from Nashville, where he works in the music industry. “I was a little scared it might be a freak show. But it’s a good blend of interesting fanatics and normal people.”

Detroit’s Joe Vaughn, 45, who’s in a Gordie Howe jersey, has come with his son Luke, 8, in a leopard-print henley and black sunglasses. Vaughn was a movie theater usher 30 years ago and saw Ferris “a million times.” Luke saw it a year and half ago, when he was 6 and half. “You want to be the coolest person like Ferris,” Vaughn says.

Luke chimes in, "He was a righteous dude!"

Later, there’s supposed to be dancing to soundtracks from Hughes movies, spun by Los Angeles DJ Richard Blade, but for now Blanchard is still talking. He tells the crowd that they got hit with a lot of last-minute fees for the parade. He says that money cut into their profits (he doesn’t tell the crowd the exact number they’d gone over budget, but it was about $10,000, or $40,000 less than Ferris’s classmates tried to raise to buy him a new kidney). “Nothing’s been canceled,” he says. “It’s all still happening.”

Finally he gets to the point: He needs more money from them. He announces what he’s calling a "Save Ferris Fest" fund. Could everyone please donate? Even $5 would help.

This wouldn't fly with the kind of person who stresses over hassles or hidden fees. Many of the festgoers paid $300, plus what it cost them to travel to Chicago and stay for the weekend, and now they’re here on opening night being asked to give even more. But for the most part, the people seem zen about it. “We’re just going to go with the flow because that’s what Ferris would do,” Vaughn says. They aren’t mad at Blanchard; they’re grateful. Over and over they tell him, “We've been so excited about this for months,” “Thank you so much,” or “This must have been so much work."

Part of what’s making them roll with chaos is that Blanchard’s one of their own. He’s a fan too. Other people might not be fine with this, but to tweak Sapphire's line in Almost Famous, “They don’t even know what it is to be a fan. Y’know? To truly love some silly little movie so much that it hurts.”

They do donate to the Save Ferris Fest fund, giving $5 or even $20. A few people threw in $100. “I bought a T-shirt and let him keep the change,” Howard says. “If you pay $300 to go to a film festival, you can throw in another $5.”

Blanchard eventually collects a little over $1,000, and isn’t worried about this request — or subsequently not disclosing the budget — alienating fans. "There's a lot of events that happen that don't say what they cost. I don't see a problem,” he tells me later. “It's not like people are forced to pay more. If they're deciding to donate we really appreciate it."

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off opens with a radio weather report: “It is a beautiful day in Chicago today.” A few moments later, after his parents leave him in his “sick” bed, he opens the curtains to reveal a bright blue sky. “How could I possibly be expected to handle school on a day like this?”

The weather on the first day of Ferris Fest is exactly like it was on Ferris’s day off, but everyone attending is stuck on a tour bus. The six coaches, named for the film’s characters, were supposed to roll out at 8:00 a.m. but it’s now 9:15 and no one’s moved. Blanchard is walking around from bus to bus, but none of the Ferris Fest staff seems to know what’s going on, and people are getting cranky. “We partied pretty hard last night and I could have used an extra hour of sleep," Howard says. Someone on the “Cameron” bus tweets, “Abt 30 mins behind schedule. Seems to be a lot of confusion amongst organizers. #LetMyCameronGo.”

Initially they’d been fired up. Every bus seems to have someone on board offering warm gummy bears — a reference to the end of the movie, when a humbled and hobbled Rooney gets on the school bus and his seatmate asks, “Gummy bear? They’ve been in my pocket. They’re real warm and soft.” Joey Hershberger, 34, who’s from Minneapolis and is on her second day of wearing her Sloane outfit, says that happened on her bus in the first minute.

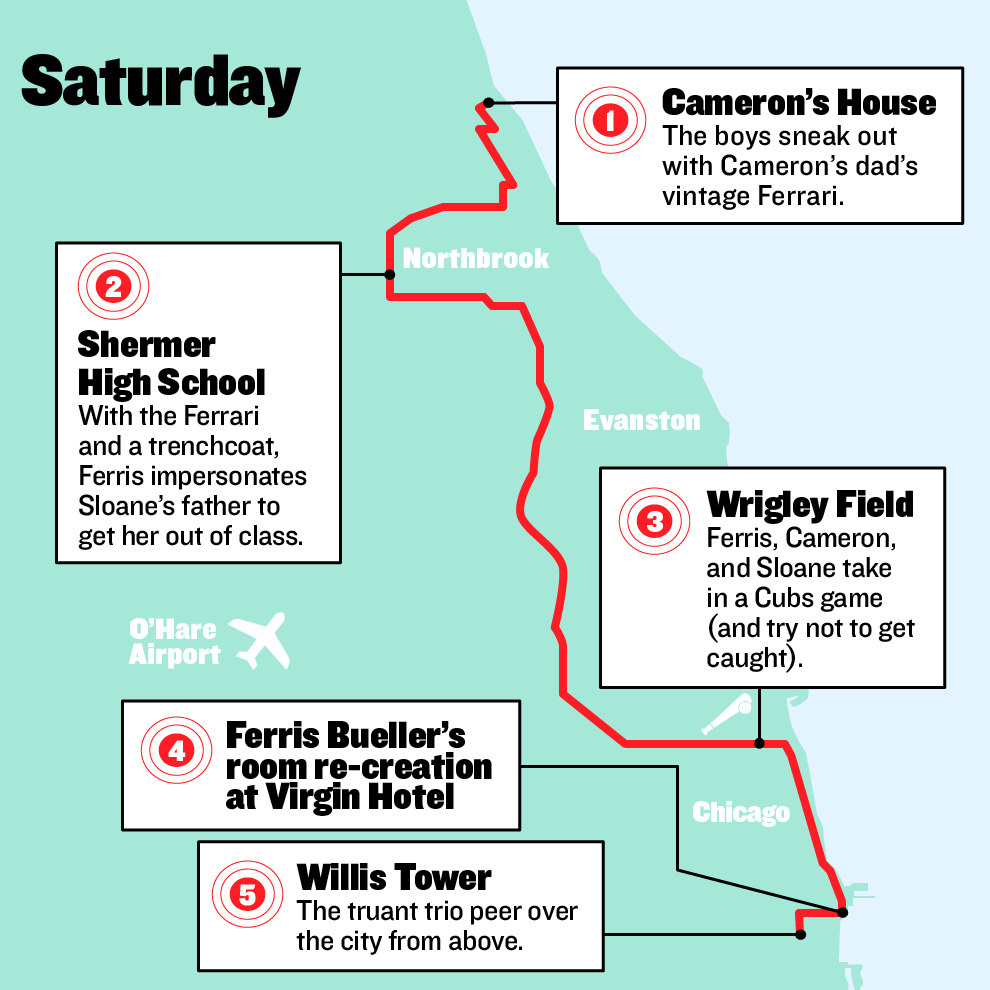

Finally, at 9:24, the “Ferris” bus, led by Blanchard, starts moving. All of the buses are going different routes, and they’re headed to Cameron’s house first.

Cameron impersonator Derrick Hill, 29, is waiting on the street in front of the Highland Park house, dressed in a Gordie Howe jersey and khakis. He looks so much like a young Alan Ruck that when he showed up at Blanchard’s hotel room a few days earlier, Sanchez screamed and shut the door in his face. He’s a waiter, not an actor, but people have been telling him for a decade that he looks like Cameron; he says strangers have even take pictures of him at work to document the resemblance. To get this gig, he bought the jersey for $30 on Amazon, put it on, and sent Blanchard a selfie.

Off to the left side of the spare, elegant house is the glass garage that Cameron’s dad really should have locked. It’s somewhat obscured by the trees, but no one is allowed to get any closer. “You can't go inside,” Blanchard says. “Please do not go on the property.”

In April, Blanchard’s plan was to knock on the owner’s door and ask for permission to bring the fest inside the garage. He asked Hill to join him wearing the jersey to help persuade the owner, who he assumed had to be at least somewhat fanatical about Ferris. The day of the rendezvous, Blanchard was running late, so Hill decided to try by himself. When the owner answered the door, Hill said, “I’m back.”

“His eyeballs popped out of his head,” Hill says. “I gave him the lowdown, but he said the house is built over a ravine so he didn’t want people tripping.” One hazard of owning a movie house, apparently: fans trekking through your yard in the dark.

So, access denied. Hill will be on the public street in front of the house until all six buses have cycled through. He’s brought a folding chair for downtime. “Bye, Cameron!” they wave as they get back on the bus after 10 minutes.

The next stop is Glenbrook North High School, which Hughes attended and used in several of his films (the football field there is the one John Bender walks across, fist raised, at the end of The Breakfast Club). The bus pulls up to see the red Ferrari replica and Ferris impersonator Ryan Stajmiger, 24, standing in front of it in an overcoat and floppy hat. He’d been the understudy for Leo Bloom in The Producers at the Mercury Theater in Chicago and gets compared to Broderick enough that when he heard about the fest, he filmed himself doing Ferris’s opening monologue and sent it to Blanchard. “When I saw the movie, I think I latched on because it's more young-boy focused and even then, Matthew Broderick meant something to me. I liked him in Inspector Gadget,” he says.

“I've got a little surprise for you guys," Blanchard says.

Up on the steps of the school, the Rooney and Sloane impersonators appear. They re-enact the scene where Sloane tells Rooney, “You're a beautiful man,” before running to meet the man in the hat and overcoat he thinks is her father.

The impersonators and the restaging are nice. Rooney looks like he was ripped from the screen, down to the sunglasses with flip-up lenses. But all day the Ferris Fest hasn't had any special access — at the school, they can't go farther than the front steps — and anyone with a car and Google could have taken themselves on the same tour. The website for Ferris Fest listed the spots where they'd be going but never specified whether they'd get to go inside, and it's clear some people are disappointed. The murmurs are loudest at Wrigley Field. (Unlike in the movie, the marquee also doesn't say SAVE FERRIS; Blanchard asked, but was told they couldn’t bump advertisers.)

Ryan Stajmiger, 24, of Chicago, who plays Ferris Bueller, with Erin Oechsel, 26, of Naperville.

But for the most part, the group are happy just to skim the surface of their favorite movie. Hershberger and her San Antonian boyfriend Dan Lindahl, 35, who’s wearing a Ferris outfit, are set on re-creating — and documenting — every scene they can. At Wrigley, Lindahl wishes he had a baseball like the one Ferris caught, so he goes to buy one at the souvenir shop across the street. As he’s posing with his arm around Hershberger/Sloane and the baseball held high, one of his busmates says, “Things are going to be boring in San Antonio after this.”

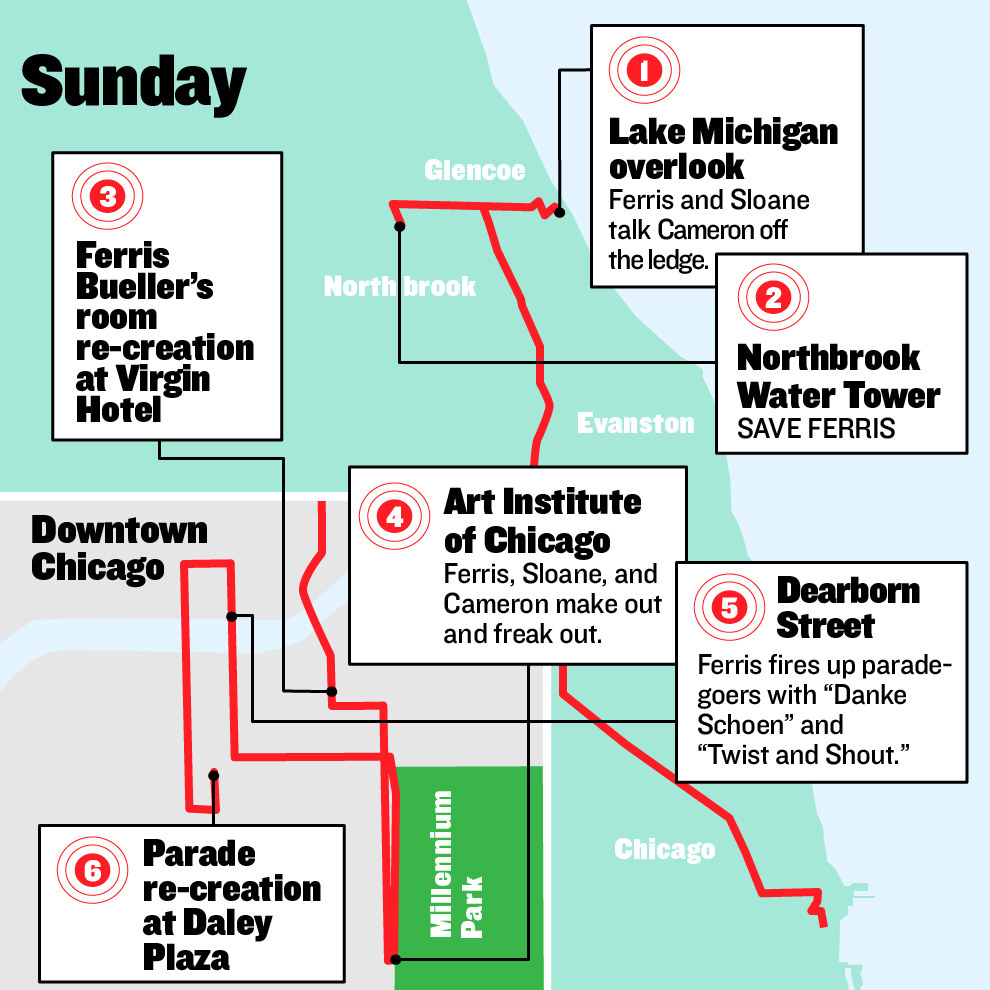

The Sloane, Cameron, and Ferris impersonators are running up the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago. They're an hour late because their driver got lost, and are now rushing to get to their positions in front of "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" (Cameron) and Chagall's America Windows (Ferris and Sloane).

At the stained glass, Ferris and Sloane kiss and cuddle, surrounded by the blue glow, like in the movie. Taveras, the guy who came from the Dominican Republic, is watching nearby. "It's like a dream," he says. "I can't believe I'm standing here. I'm overwhelmed."

In another gallery, Hill as Cameron is staring at Georges Seurat's pointillism. All around him the attendees are laughing and posing; today, they've switched out the warm gummy bears for mimosas and Bloody Marys. But Hill is quieter; he's thinking about the parade re-creation that's happening in a few hours. "It's going to be more crazy than this whole weekend combined," he says. "I'm nervous. My stomach is in knots."

A few minutes later Blanchard rounds up his impersonators — they have to get to the parade site now. They sprint through the museum and out on the street. Blanchard is frantic at this point, turning down a bystander who wants a picture. "Sorry, we don't have time!" he says.

When they get to Daley Plaza, though, not much is happening. The German float is tucked away in one corner, but otherwise the open space — dominated by an untitled cubist Picasso sculpture — is mostly empty. The email with the parade’s location was sent out at noon, but besides a retired police officer and his wife, who asked another officer where the permit for the parade had been pulled, no one else seems to be waiting for it to start.

ABC Floats' Neary and Fiene are leaning against a wall watching the fräuleins pose for pictures with some passersby. "We're excited," Fiene deadpans. "Can't you tell by our faces?"

At 1:56 p.m., a couple of guys start to put up barricades. The route is only through the plaza and the area that's lined with the metal fences is only about two blocks long. The end is closed off with a fence too, alarming the leader of the dance team. "What is the exit?" she asks. Blanchard never did have time to do the run-through with the cars on the table to show everyone where to go.

"You guys are all going to perform and then go back behind the float," he says. "Go single file back behind the parade float."

Blanchard asks the barricade dudes to create a pen right in front of where the performances are going to happen, for the people who've paid $300 for all three days of the fest.

The crowd comes all at once, and with about 30 minutes to go, what looks like a thousand people are already lining the sides of the barricades. All of the front-row spots are gone. Three-day people are rushing to their area as soon as they're alerted to it. Vaughn and his son Luke snag the last front row spot in the pen, with Luke standing on the bottom rail of the barricade so he's tall enough to see over it.

The small space is packed full when the people from the “Ferris” bus arrive. "Wow, this is insane," Hershberger says as she and her busmates are escorted to their special box.

And this is when people who’ve been forcing themselves to be chill all weekend start screaming at each other. The “Ferris” group are now in front of the people behind the barricade, who have the same tickets and got there first. The security team asks them to get behind the rest of the crowd, but they refuse. An Australian guy named Simon, who'd gotten a standing ovation the day before for supplying his bus with booze, is the loudest.

"If you touch me, I yell rat," he hollers at a guard. Another bystander offers to punch Simon on the guard’s behalf, and pretty soon everyone is pissed. The “Ferris” group haven’t moved and are still in front of everyone else inside the metal fence.

"Ferris Fest is the most fun you can have while never knowing what the fuck is going on."

The parade should be starting at 3, but the marching groups aren't lined up yet and no one can find Blanchard. "I think he's flossing," a Ferris Fest staffer says.

At 2:59, Neary and Fiene march down the route and into the mess at the end with another problem. "The Ferrari isn't allowed," Fiene says about the plan to have the car be part of the parade. "It's not allowed on the plaza. The city just pulled it."

"Shit, where's David?" another staffer says. "I'll text him."

Observing this, a festgoer in the special pen remarks, "Ferris Fest is the most fun you can have while never knowing what the fuck is going on."

At 3:12, Blanchard reappears at the front of the route.

His event director, Cindy Smith, screams at him, "You've got to start."

"I'm trying to start!" he hollers back.

It seems quite possible at this point that Blanchard might, like Cameron in the backseat of the Ferrari, go berserk. But he’s still for only a moment, and instead of becoming catatonic, perseveres. He sends the dance team out first. The “Ferris” group has compromised with the guard by sitting in front of the barricades. The South Shore Drill Team and the King College Prep marching band follow the dance team. It’s hard to see the performances if you’re not right in front of them, and the crowd seems a little bored. Then, the Ferris character actors walk out with the float behind them. Over the loudspeaker, Blanchard says, "The moment everyone has been waiting for. You've seen it 100, maybe 200 times, but it never gets old. The 'Twist and Shout' parade float scene!"

Everyone in front of the barricade is standing now. There is still some yelling for people to get out of the way, but for the most part, the crowd is transported to that famous downtown Chicago moment. Luke sings along with “Danke Schoen” as Ferris/Stajmiger lip-synchs and the fräuleins bob around him. When "Twist and Shout" starts, there's a happy scrum in front of the float. The people from the “Ferris” bus are bouncing around with the Ferris character actors. Edie McClurg is grinning and twisting. Cameron/Hill locks eyes with her and they start grooving together. All around the float everyone is singing, "Shake it up baaaaaby." "This is the best day of my life," one Ferris Fest–goer yells to Lyman Ward, stealing Cameron's line from the film.

When it's over, everyone claps and cheers for a few minutes. In the movie version of this story, Blanchard would hop on the float with Ferris, waving and acknowledging the crowd alongside the impersonator. But real life doesn’t usually provide movie endings. And even though he’s technically pulled off the fest, it’d be difficult to say that Blanchard is as triumphant right now as Ferris was when he made it home to his bed without being caught. It’s not that he’s failed either, like Rooney, and should be limping away from the scene. He’s finished the weekend somewhere in the middle, neither the hero nor the loser, and instead of being atop the float, he’s on the sidelines holding his checkbook and looking around. The head of the dance team is next to him waiting to be paid, and he needs to find a pen.

Blanchard’s back in L.A., driving to Smith’s house to do a postmortem on the fest. He’s still drumming up donations for the Save Ferris Fest fund and has set up a GoFundMe page in hopes of raising $10,000 to tackle outstanding bills and create funds for a follow-up event (at press time, people had given $940). “Everything we did, I'd do again,” he says. “The bus tours, the stars, the autographs, all of that was fantastic.” He hopes to do it again in 2021 to celebrate the film’s 35th birthday.

Blanchard's favorite part of the weekend was at the Art Institute. He was running late and only had five minutes there — Smith was telling him to get to the parade — but he stopped cold when he saw Cameron/Hill in front of the Seurat. “It was really important to me to drink in that moment,” he says. He asked someone to take a picture of him standing there next to Hill, who put his hand on Blanchard's shoulder, and that image is what has stuck with him. “Not to give myself praise but when I saw it, it really kind of spoke to me. I saw how well things went. I felt like John Hughes was saying, ‘You done us right. You came here and you did this with honor and respect and you did us right.’” ●