Hannah Giorgis is an Ethiopian-American writer based in New York. Safy-Hallan Farah is a Somali-American writer based in Minneapolis. In October, Safy facilitated an "Everything you believe about East African women is wrong" Twitter discussion. Hannah's contributions to the discussion led to conversations between her and Safy. Here, they explore the topic in greater depth together, using the life stories of women in their respective families.

Fadumo, tall and svelte, wasn't a woman yet, not by the standards of her time. She wasn't old enough for her sins to be counted — that happens at 15 in Islam. She wasn't fully developed, and she didn't know how to say "no" yet.

But her soon-to-be husband — 40 years her senior — was a man. He was the kind of man who honored his family and clan. Toward Fadumo, he was clinical and cold. So when her father said, "This is your husband," she did what most teenagers could probably only fantasize about: She ran away.

Her mother told her to leave their no-name village in northern Somalia to go live with relatives in Aden, Yemen. She told her, "Run away as fast as you can and never look back." Carrying a knife, some fabric, and the clothes on her back, Fadumo left in the middle of the night. In case of lions, her mother instructed her to stay awake during the night, climb up into a tree, and use the fabric to tether herself to it. Fadumo ran until there was no running left, until she crossed the Red Sea on a boat.

The distance between where Fadumo was headed and where she was meant the difference between freedom and dependence, between life and death. In Aden, Fadumo eventually married the son of a prominent Somali-Yemeni family — a husband of her own choosing. With him, Fadumo had Khadija who had Shukri. Shukri flew from Mogadishu to study in Rome at age 17 and had Safy years later, in her early twenties. If Fadumo listened to her father, her life, and the lives of Shukri and Safy, would have been lost in transmutation; the changing tides would have washed over her memory.

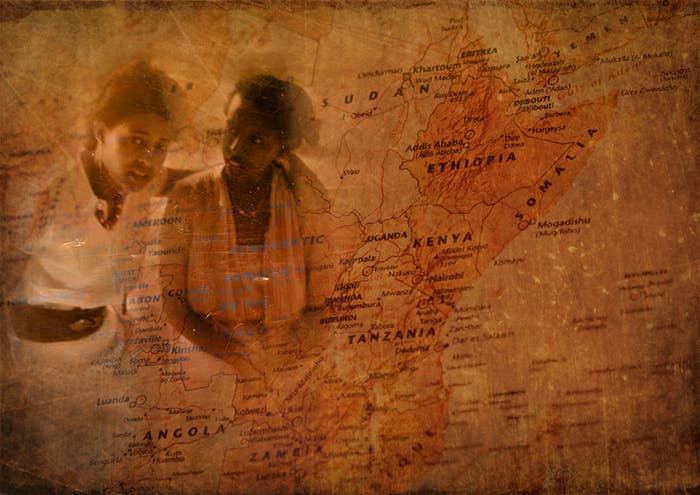

East African womanhood is a minefield between the region's war zones and too-simple Western understanding thereof. The experiences of women from Ethiopia and Somalia serve largely as a barometer of the nations' violence. But our foremothers taught us resistance long before we had a name for it. Their stories alchemize the violence that forced them out of the arms of their families and toward countries that don't recognize their strength. Spinning blood into honey and bone into gold, they transformed their pain into our power.

In the parts of East Africa our ancestors are from, warfare and political and religious tension prevent women from cultivating connections across borders. But in America, our experiences overlap in ways that illuminate our shared history. To be from East Africa is to bear the mark of our region's hurt and pain. We're called upon to explain famine and female genital mutilation, veils and victimhood. Our foremothers taught us that these scripts don't define us, even when prepackaged stereotypes offer us convenient roles to slip into. Their stories complicate the Western feminism that paints them as objects of rescue rather than subjects with agency.

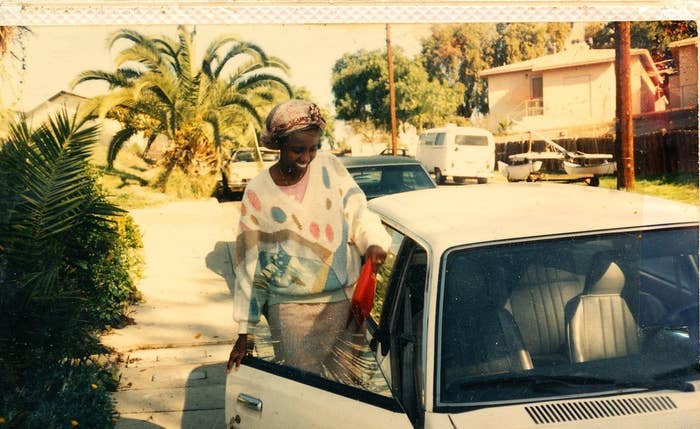

Aida spent much of the 1980s waiting tables, paid under the table, saving her cash to support herself and her younger sister after they earned their education on American student visas during the height of Ethiopia's Red Terror. In the years leading up to their emigration, the Derg regime had killed over 10,000 people, a national trauma whose scars are still evident.

Immigrant women barely into their twenties, Aida and her sister shared a tiny studio apartment with their cousin, balancing heavy books and weightier burdens. During breaks between classes and her several jobs, Aida cooked, counseled, and connected relatives to one another, using phone cards that doubled as lifelines to call family "back home." She and her cousins huddled closely in merciless February cold. Ethiopia's most frigid nights rarely dip below 40 degrees, but the diabolical winter in Queens, New York, made waiting for buses after work a regularly scheduled adventure in temporary cryogenics. Back then, the regulars she served at Ethiopian restaurants were immigrants as well, longing for a taste of home.

Still, Aida's weekends were icy but vibrant, full of train rides into Manhattan to dance to Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson's latest hits in sequined miniskirts she now keeps buried in her closet. And the warmth shared among her close friends and community formed a patchwork of immigrant resilience that held strong under the weight of stressors both atmospheric and cultural. Together they weathered the Reagan-era torrent of anti-immigrant sentiment, and Aida eventually left New York for the warmth of the California sunshine and the man who would become the father of her four children — Hannah, Rebecca, Moses, and David.

We write overlapping stories today but grew up worlds apart from each other — one an Ethiopian girl under California sun, the other a Somali girl enduring Minneapolis winters that refused to cooperate with her. But our experiences as young East African women in America are imbued with the same sense of danger (violence at the hands of men) and uncertainty (economic and otherwise) that our foremothers understood on the other side of the world. After all, Shukri and Aida did not inherit prosperity when they came to America. They got a mixed bag of opportunity and dismay: With every hurdle leap toward the American dream, there was the kickback of dust and debt.

As black, immigrant women in a country that penalizes all three, we carry cumulative burdens and find ways to dance underneath the weight. The revelry has come slowly, through sharing stories with one another, first on Twitter and later in the spaces where we live and write.

Aida showed us that words can make magic. She makes phone calls as she cooks, cleans, categorizes, catches, contorts. Her voice is soothing, full of warmth. To receive a phone call from her is to know you are loved — wherever you may be — part of her patchwork, and she wants you to know your beauty completes the whole. Relatives everywhere from Canada to Ethiopia sense the honey in her "hello," and in the Ethiopian proverbs that roll gently off her tongue, even when she's scolding. The one she repeats most often is simple. Translated into English, it highlights the beauty of the collectivism she and the women around her model: "For one person, 50 lemons is a burden. But for 50 people, those same 50 lemons are simply decorations."

Indebted to ancestry that forms the mosaic of our identities, we are composites of the women who came before us. We are the products of their survival, resilience, creativity, and collective brilliance. Rejecting submission while caring deeply for one another, they forged a kind of feminism that found its power in the collective. They carried each other, sometimes literally, across borders and milestones. With the maps our foremothers have passed down to us, we're creating a promised land for ourselves and for the women whose names have been forgotten.