WILMINGTON, Delaware — It was the summer of 1975, and Joe Biden felt the need to reassure his constituents back home: His vote the year before that helped save busing as an option to desegregate schools didn’t mean he supported the practice.

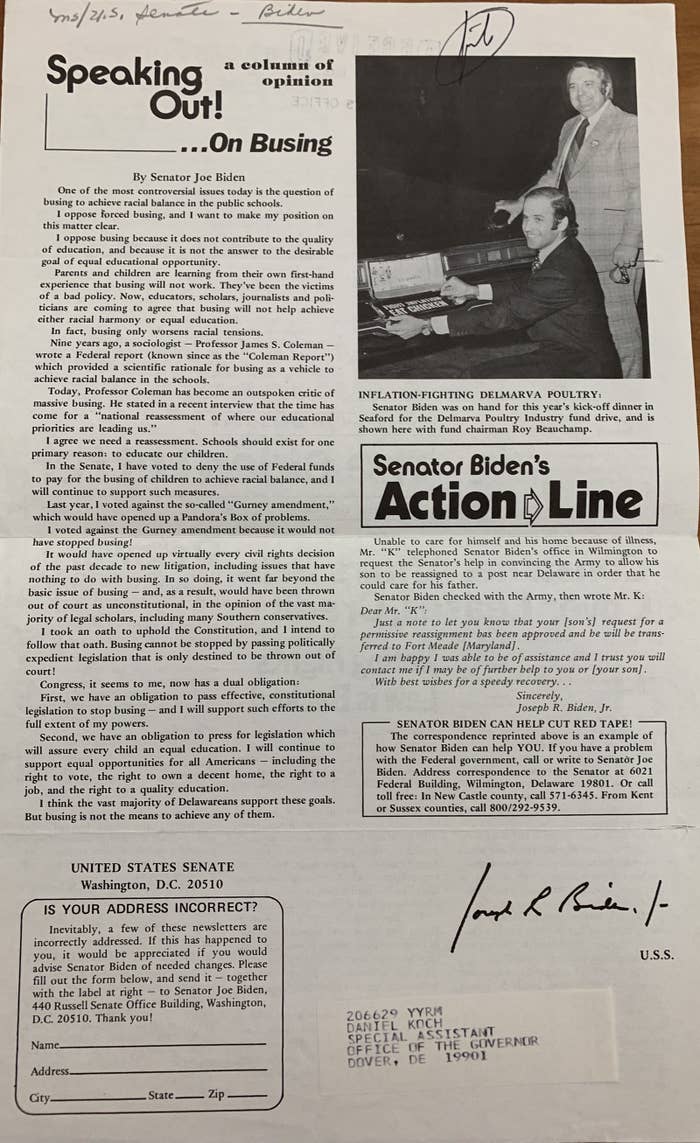

“I oppose forced busing, and I want to make my position on this matter clear,” the then-32-year-old senator wrote in the Biden Letter, a newsletter his office circulated.

“I oppose busing because it does not contribute to the quality of education, and because it is not the answer to the desirable goal of equal educational opportunity,” Biden continued, before explaining that he voted against a provision, known as the Gurney amendment, that would have barred the federal government from ordering busing, because of the “Pandora’s Box of problems” that made it vulnerable to a constitutional challenge. He believed the bill went too far.

“It would have opened up virtually every civil rights decision of the past decade to new litigation, including issues that have nothing to do with busing,” he wrote.

“Busing cannot be stopped by passing politically expedient legislation that is only destined to be thrown out of court!”

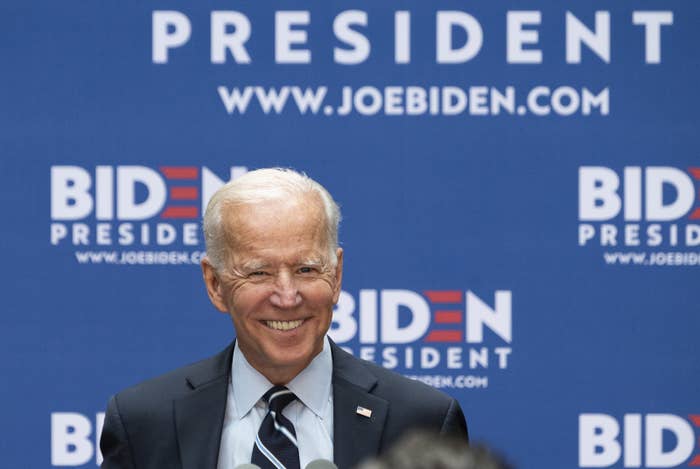

The 44-year-old newsletter — one of two Biden Letters stored at the Delaware Public Archives and viewed this week by BuzzFeed News — underscores the pressure Biden was under at the time. The idea of busing was quite unpopular among white voters in his small state, but also among some of the local black activists whose perspectives helped inform Biden. Now, as he runs for president in a Democratic primary that is playing out in a much more progressive era, especially on issues of race, Biden is eager to persuade people he wasn’t on the wrong side of history.

Biden now casts his Gurney vote in a different light. Where before he framed his decision as a technicality that should by no means raise doubts about his anti-busing views, he now frames it as a principled stand he took in spite of the political risks.

“I’ve always been in favor of using federal authority to overcome state-initiated segregation,” Biden told the Rev. Jesse Jackson and his Rainbow PUSH Coalition last month. “In fact, I cast a deciding vote in 1974 against an amendment called the Gurney amendment, which would have banned the right of the federal courts to be able to use busing as a remedy. And you might guess in the middle of the most extensive busing order in American history in my city and state, it wasn’t what you’d call the most popular vote in the country at the time.”

His vote on the Gurney amendment did help kill the provision: The vote was just 47–46. Edward Brooke, the only black US senator at the time, said leading up to the vote that the amendment would have brought local schools “back to the age of Jim Crow.”

Biden’s remarks to Jackson’s organization came the day after Sen. Kamala Harris of California turned Biden’s long-held opposition to busing — and his fond recollections of working with segregationist senators — into a searing attack during the first Democratic presidential debate, raising her own experience of being bused as a child in Berkley, California, to an integrated school under a voluntary program. The remarks also speak to a fragile balance the former vice president is trying to strike: owning his past, by explaining that he was representing Delawareans’ interests, while softening the hard line he once took.

The strategy includes putting black Delaware leaders who opposed busing in front of reporters. Here this week near Biden’s home base, a campaign aide supervised interviews with two longtime friends who expressed frustration with how Harris and others have attacked Biden.

“For her to say that she is what she is because of the opportunity she got in a so-called desegregated school — excuse my French, that’s bullshit,” Bebe Coker, a Wilmington activist, said of Harris. “Where does she think that every major lawyer, doctor, or whatever in our race of people came from?”

“If that’s the reason she is where she is, she needs to go back and start again,” Coker continued. “And I’m not being funny. I’m dead serious. That’s sad. You’re going to sit here and put your success on the fact that you sat in a physically arranged bunch of chairs and desks in a classroom with white kids, and this is why you’re the way you are? Oh, lord, it makes me throw up. But, anyway, such is life. And California to boot! Come on. Come on. Uh-uh.”

A spokesperson for Harris’s campaign declined to comment.

Richard “Mouse” Smith, a local NAACP official who has been close with Biden since the 1960s, said Biden has strong ties to Delaware’s black community, dating to his days as the only white lifeguard at a city pool and his early legal work as a public defender. When Biden was starting out in politics, Smith introduced him around Wilmington’s housing projects.

This week, Smith recalled his advice to Biden: “If a roach or mouse runs over top of you, don’t move. If they give you a mayonnaise jar with some orange Kool-Aid with a little bit of ice in it, you drink it. If they offer some food, eat. Listen to them.”

Anti-busing views were not as prevalent in the black community, Coker said, but she and Smith found Biden sympathetic to their arguments that it was counterproductive to force children, in the name of desegregation, to wake up hours earlier to be sent to a white suburban school district. Biden has said over the years that he supported the overarching idea of desegregating schools, but not forced busing as a means to achieve it. He and his allies note how he favored programs to promote more equality in housing and improvements to existing schools and neighborhoods — measures they believe would have led to more organic integration.

Coker had a high school, middle school, and elementary school within walking distance from her home, and a daughter enrolled in each.

“Now you tell me,” she said, “why I would want my kids to get up at 6 o’clock in the morning and be on the bus at a quarter to 7 to go to West Hill.”

“We didn’t want busing, period,” said Smith. “Busing was doing nothing for us.”

These pragmatic concerns from pockets of the black community aside, white opposition to busing was more pronounced and widespread at the time and often carried a racist undercurrent. Biden felt the heat at home, as he recalled in his 2007 political memoir, Promises to Keep.

“I’ll never forget the annual Chicken Festival in 1978, which drew big crowds in downstate Delaware,” he wrote. A woman in the parking lot started shouting after him. “She was thirty yards away and closing fast. An attractive blonde about my age, she was hurrying toward me with two little boys in tow. She had a big grin on her face, and as she got close to me, she turned to her sons and said, ‘Boys, I want you to meet Senator Biden. Take a very good look at him. This is the man who has ruined your life. … It’s because of him you’re going to be bused.”

The woman cut Biden off before he could correct her.

Biden has said President Donald Trump’s “very fine people on both sides” response to the 2017 white supremacist riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, motivated him to launch a third White House bid. And he has championed other civil rights causes throughout his career as a senator and as vice president under Barack Obama — a fact he and his campaign lean on heavily when parrying criticism on race issues.

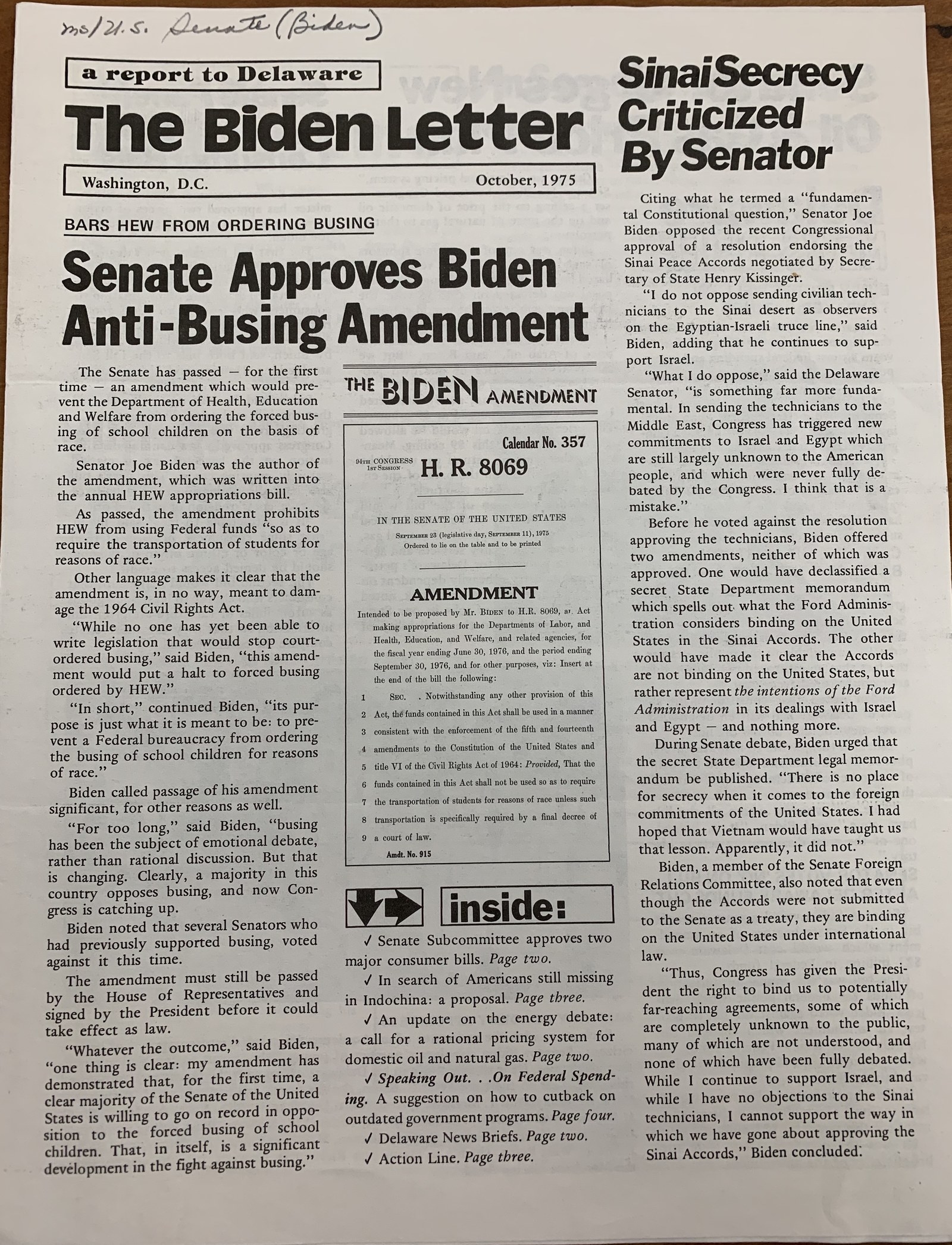

The July 1975 edition of the Biden Letter included a front-page piece touting his cosponsorship of a bill to extend the Voting Rights Act. The other pamphlet available at the state archives, from October 1975, came with “Senate Approves Biden Anti-Busing Amendment” as its top headline, but also a blurb about Biden advancing a bill to ban discriminatory credit lending practices on the basis of age, race, color, religion, or national origin.

In his 2007 book, Biden recalled worrying with a close adviser about the effect the busing debate could have on his first Senate reelection campaign.

“How would a challenger, we asked, take down Joe Biden? It wasn’t complicated. Point out Joe Biden’s strong commitment to civil rights and civil liberties. Point out his statements that he’d gotten into politics largely because of civil rights. Joe Biden’s a card-carrying liberal, a challenger could tell people, and his campaign to minimize court-ordered busing is just a Trojan horse. Once Joe Biden was safely elected for another six years, he’ll pull the rug out from under the antibusing lobby.”

Biden never did, though in the book he attributed his Gurney vote to a belief that “courts had to be able to stop government-enforced segregation.” Biden also at times waded into other racially charged fights, like in 1986 when he urged blacks to reject Jesse Jackson — then a presidential rival — as a leader for their cause.

Smith said recent attacks and reflections on Biden’s record bother him because “he ain’t a racist.”

“I’m probably more racist than he is,” Smith said. “He is not a taker. He’s a giver. Do you think he could last 36 years in the Senate if he was a racist? Do you think he could have my friendship if he was a racist?”

Such views of Biden were not shared universally in Delaware or by civil rights leaders elsewhere. During Senate hearings in 1977 for a Biden anti-busing bill, Clarence Mitchell, a top NAACP leader, attributed the effort to “racism … deep in the state of Delaware,” according to coverage from the Morning News of Wilmington. Biden’s voice nearly cracked as he pushed back: “I thought my record, albeit brief, was enough to get beyond insinuations of racism.”

More recently, Jackson — as he prepared to host Biden the day after the Harris hit — told USA Today that Biden’s busing stance “doesn’t make him a bad guy, but it puts him on the other team.”

Biden’s comments over the years about the working relationships or friendships he forged with segregationists, such as James Eastland, John Stennis, and Strom Thurmond — relationships strengthened in some cases by common cause on busing — also have opened old wounds. The recent criticism from Harris and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey stemmed from Biden’s remarks last month at a fundraiser. “He never called me boy,” Biden said of Eastland, prompting reminders that “boy” has often been used as a pejorative for black men.

“When they say he was … praising white, racist people, let me tell you something: If a white, racist person cut a deal that’s going to benefit my people, yes, I’m going to give them recognition, but I’m still going to be on his ass,” said Smith. “And I’m going to stay on his ass.”

“Sometimes you have to deal with the devil to get a deal done,” Smith added, before acknowledging he was disappointed with the “boy” remark. “The only thing I said to him — I would say to him, is, Joe, take ‘boy’ out of your vocabulary. Don’t use that.”

In their separate interviews, Coker and Smith both used similar phrasing to suggest Harris caught Biden off guard, though Biden advisers said before the debate that he was prepared for such an attack. (“I would love to have the opportunity to debate her,” Coker said.)

They also suggested Biden’s clunky response to Harris, which had a tinge of “states rights” sentiment that’s been used by others to excuse racist policies, was an inelegant way of explaining that he was doing right by locals who expected him to oppose busing.

“Come to us,” Smith said. “This decision wasn’t made behind the closed door of Washington. This decision was made by the good people of the state of Delaware.”