The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

CLEVELAND — Not long after Mike DeWine became Ohio’s governor last year, people noticed all of the fun he was having with the ceremonial duties. At 72, he finally got the job he always wanted. There was no ribbon-cutting too small, no photo op too corny. He was, as one lobbyist observed to a reporter in Columbus, “Ohio’s Grandpa.”

The image wasn’t entirely favorable. Even a few of his fellow Republicans wondered if DeWine was coasting, treating the governor’s mansion as some sort of retirement home after four decades in public life.

But the last few weeks have been a revelation for DeWine’s doubters and vindication for those who believed his governorship could be more than a capstone. He has asserted himself as a national example for how to manage the coronavirus crisis, combining a reassuring presence with aggressive action. He understood earlier than other governors that closing schools, restaurants, and bars — as disruptive as those decisions were — would help contain COVID-19’s spread. He took unprecedented steps to preempt his state’s presidential primary and keep voters at home.

DeWine’s paternal instincts used to prompt snickers, his decades grinding through public office discounted as the bloodless work of a career politician. But in a crisis, where DeWine has parlayed 40 years of government experience into calm and quick decisiveness, those old weaknesses now project as strengths.

“Sometimes you have an instinct based on the facts,” DeWine said by telephone Thursday, in between local radio interviews and a call with the state’s mayors. “When I have not trusted my instincts, I've made mistakes. My instinct throughout this has been that we’ve got to move faster.”

Republicans are happy to rally around DeWine even as they wrestle with uncomfortable questions about how he has approached the pandemic with more urgency than President Donald Trump has. Many Democrats are lauding his approach too.

“The good governors, and DeWine has been one of them in this, know they have to drive this because we have a president who has been AWOL on this — worse than AWOL, he’s caused damage to their efforts,” Sen. Sherrod Brown, a past DeWine rival, told me. “DeWine won’t say that. I would think he wouldn’t, but of course he knows that. We all know that.”

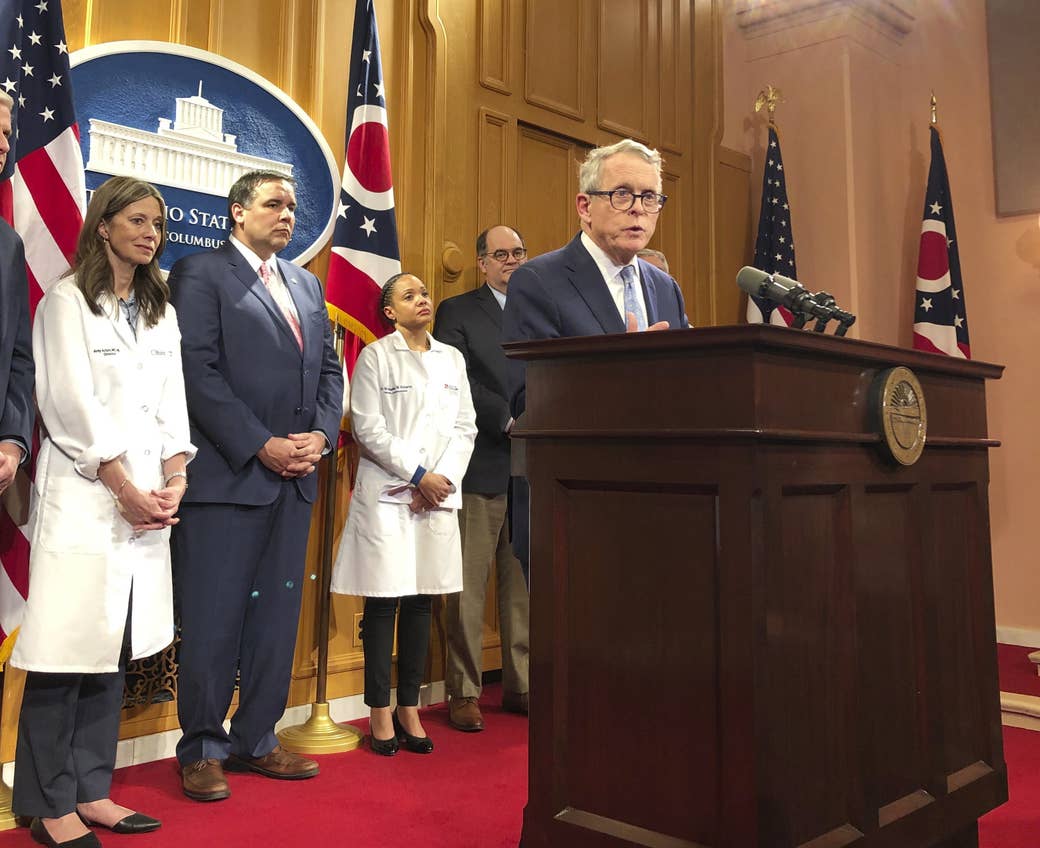

Citizens who don’t ordinarily tune in to state government are tuning in for DeWine’s daily press conferences. The afternoon briefings, where he relies on the expertise of his health director, a medical doctor with a master’s degree in public health, are appointment viewing. I’ve been an Ohio resident for all of my 38 years. Mike DeWine has held one public office or another for almost all of them. I can’t remember him being an actual household name here until now.

“I think he’s treating Ohio like he would treat his own family,” John Kasich, DeWine’s Republican predecessor as governor, told me approvingly, echoing a sentiment others shared.

When I spoke this week with DeWine and his close friends and colleagues, all of them talked — in a way that would seem cultish or at least scripted if it wasn’t true — about how this job, being governor, is the job he prepared for his entire life. He’d been a county prosecutor and state lawmaker. He’d served in both chambers of Congress. He’d been the lieutenant governor and the state’s attorney general.

“We all talk about career politicians and people like that,” Lt. Gov. Jon Husted, who appears with DeWine at the daily press conferences, told me as he began to laugh. “But this is probably one time that you want a guy like Mike DeWine in charge — because he’s seen it all, and you’re not going to slip anything by him. He was built for this moment.”

The most notable thing about DeWine’s career might be its longevity. Until now, he wasn’t defined by a signature achievement or piece of legislation. The work that stands out most might be clearing a huge backlog of untested rape kits while he was attorney general. During the types of historical events that friends say informed DeWine’s approach to crises, he was mostly a bystander. As lieutenant governor, he watched his boss, the late George Voinovich, deal with the deadly Lucasville prison riot. He experienced 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina as a senator.

Ideologically, DeWine rates as a social conservative. He signed into law last year a ban on abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected. (Kasich twice vetoed versions of the bill while he was governor.) A question that animated the closing days of the 2018 gubernatorial race was whether DeWine was more of a Donald Trump Republican or a John Kasich Republican. He and his allies argued he was neither — he was a Mike DeWine Republican. The “heartbeat bill” notwithstanding, DeWine is more in sync with Kasich’s old-guard mainstream conservatism than Trump’s populism. But his political identity is tethered more to his personality and to his family than to any ideology.

DeWine cultivates a homey image. You wouldn’t know by the suits that hang off his short and slender frame that he’s the kind of guy who can loan his campaign $4 million, thanks largely to his family’s seed and twine businesses. (When I saw him sporting new and fashionable eyeglasses at the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland, I joked it was a sure sign he was running for governor.) He met his wife, Fran, when he was in the first grade. They married in college, had eight children, and settled in for a life as political partners. No one in his tight circle of advisers has as much influence on his decision-making as Fran does, J.B. Hadden, a lawyer who’s been close to DeWine and his family for more than 30 years, told me.

Fran is a constant presence at DeWine’s side, often sporting an “I Like Mike” button with “Like” crossed out and replaced with “Love.” When DeWine turned over the first portion of his Wednesday coronavirus press conference to her, she encouraged parents to read and cook with their kids as a way to pass time during self-isolation and school closings.

Friends said the death of the DeWines’ 22-year-old daughter Becky in a 1993 car accident shaped them more than any political event. “It’s internal, but it’s profound,” Hadden told me. “It’s what drives the two of them.”

DeWine was in the midst of his second Senate bid at the time. This one would be successful. But Washington wasn’t where he wanted to be long-term. As Hadden described it, DeWine found himself lulled into seeking a third term in 2006. “Back in ’05 I think he decided in his head, he could tell things were getting rough for Republicans,” Hadden said. “I think he just decided he was going to stay in the Senate for the rest of his life. If Sherrod wouldn’t have run, Mike DeWine probably wouldn’t be governor right now. He’d have been reelected and unhappy in the job. He always wanted to be governor.”

Brown beat DeWine in a heated campaign that exposed some of DeWine’s questionable judgment. In an ad accusing Brown of being soft on terrorism, DeWine’s campaign used an altered image of the World Trade Center towers burning on 9/11. As DeWine suspected, 2006 was a terrible year for Republicans. Brown won. DeWine went home. Fourteen years later, as DeWine leads Ohio through a crisis, Brown is one of his biggest fans.

“It’s not surprising,” Brown told me when I asked if it was, given their acrimonious history, “because he’s an honorable elected official, and I thought that running against him.”

Brown said he’s been talking and texting with DeWine, mostly about how they can share information that would be helpful as Brown fights for more federal resources. “Quarterbacks are better when they have experience,” Brown said. “DeWine could not do this so well if he didn’t have a breadth of experience understanding the way government works.”

In the middle of intense partisanship and frustration over how Trump has handled the coronavirus response so far, Democrats have been exuberant in their praise for DeWine. David Pepper, who failed in a bid to unseat DeWine as attorney general in 2014 and now chairs the Ohio Democratic Party, has cheered DeWine’s response. Emilia Sykes, the Democratic leader in the Ohio House of Representatives, told me she has largely positive views of DeWine’s efforts. “What DeWine is showing us is what happens when you have someone experienced in this role,” she said. “The reach goes far, the relationships are long.”

Sykes has been especially impressed with DeWine’s empowerment of Amy Acton, the health director who’s been a major presence at the daily press conferences. Acton has built up her own devoted following: An Ohio T-shirt company printed a tribute to her this week; a TV reporter presented her with flowers Thursday.

DeWine allies point to Acton’s appointment last year as a testament to good judgment. The top spot at the Ohio Department of Health can be a soft landing for patronage hires or career bureaucrats. It was the last Cabinet post DeWine filled, at least in part because he took time to find someone with both experience in public health and strong communication skills.

“A lot of times people hire administrators,” Husted, DeWine’s lieutenant governor, observed. “He wanted to hire a doctor that really understood how public health worked. It was that decision that put Amy Acton in that place. Who better could you have in that position at this moment?”

Acton “has been both that voice of confidence and authority but also reassurance,” Frank LaRose, Ohio’s Republican secretary of state, told me. “She’s been reassuring to Ohioans while at the same time not sugarcoating things. He’s been right there by her side saying, ‘I’m the governor, the buck stops here, and what my health director says is law.’”

The choices DeWine and Acton have made together this month have been tough, even as they’ve since been replicated across the country. DeWine, a traditional, pro-business Republican, has found himself telling restaurants and bars they could only stay open for takeout or delivery and ordering the closings of gyms, movie theaters, barbershops, and hair and nail salons. He told me he struggled with balancing the loss of jobs against the loss of life. “The decisions we’re making throw some people out of work, I mean literally,” DeWine said. “But we’ve got to balance that with...we’ve got to get them through it.”

Pat Tiberi, a Republican who served in Congress with DeWine and now leads the Ohio Business Roundtable, told me DeWine sought input from the private sector. “He’s the type of elected official who’s deliberative but then acts. Whether you agree with him or not — and I tend to agree with almost everything he's done — you can't say he isn't listening, reaching out.”

Friends cringe about how casual DeWine is about handing out his personal cellphone number, but the move has created an information network that has helped serve as a gut check. On Sunday, for example, DeWine received texts from people worried about how crowded bars were the night before. That day, he and Acton announced the bar and restaurant restrictions.

DeWine’s moves have not gone without criticism. Larry Householder, the Republican speaker of the Ohio House and one of the most ambitious politicians in the state, fired off a tweet urging the governor against a restaurant shutdown, drawing an attaboy from DeWine’s Republican successor as attorney general.

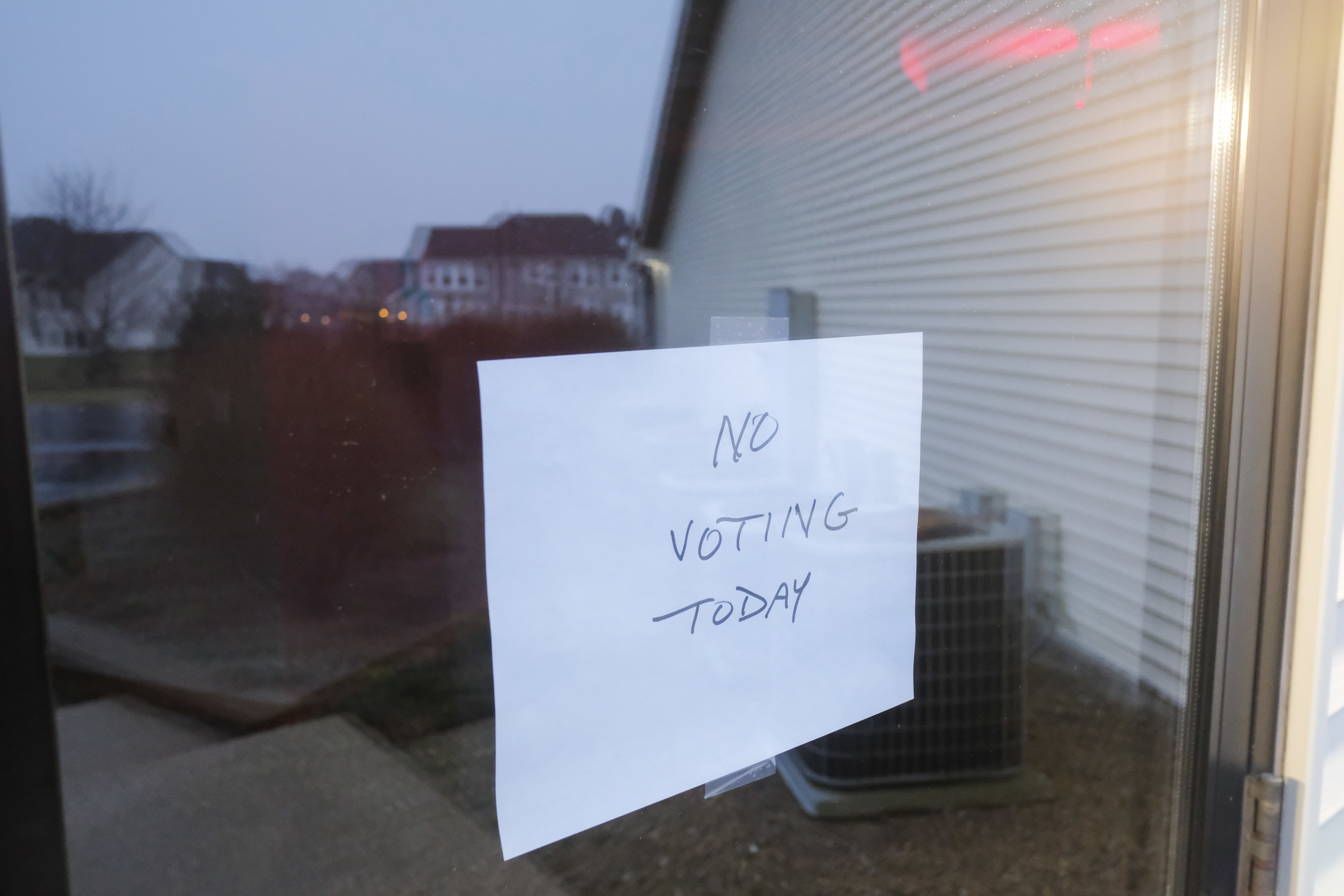

And DeWine’s efforts to postpone Ohio’s presidential primary were particularly messy. On Monday, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised against gatherings larger than 50 people, DeWine determined holding in-person voting the next day would be a health risk. But because of provisions in Ohio law and a legislature that no one was sure could convene under the circumstances, DeWine asked Husted, a former secretary of state to work with LaRose to find a solution. The result was a last-minute, third-party lawsuit to delay the primary until June and allow absentee voting in the meantime. A judge ruled against the plaintiffs, and for several hours Monday night there was chaos, as no one knew if polls would open the next morning. Finally, DeWine and Acton invoked a health emergency to keep the polls closed. If and when a new vote will be scheduled remains unclear.

The emergency closing, LaRose told me, was essentially a last resort. The lawyerly DeWine didn’t want to do an end run around the courts if he didn’t have to. “It wasn’t because of indecisiveness,” said LaRose, addressing the second-guessing that DeWine should have set the postponement in motion days earlier. “It was because of new science.”

Those who know DeWine best told me the politics surrounding the coronavirus matter little to him. That’s been evident in how far ahead of Trump he’s been. Other Republican governors who take their cues from the president have been slower to react, hemming, hawing, and encouraging their citizens to “go to Bob Evans and eat.” DeWine has been careful not to frame his approach as a contrast to Trump’s, and he and his allies mostly parried my questions about the obvious differences.

“Look,” DeWine told me Thursday, “I think a public health crisis is naturally the province of the governor, and that people look to a governor, they look to their mayor. These are the things we inherently have the power to deal with.”

He said Trump’s administration has been helpful throughout the crisis: “I feel good about that relationship.” He praised the Agriculture Department for granting a waiver that allows the state to keep school meal programs running while the buildings are closed. “We can pick up the phone if we’ve got a problem and we can find somebody to help drive it through.”

Others turned the Trump questions around to gently suggest DeWine is showing that experience in government, something Trump lacked before he was elected, matters.

“I guess at this point in my life, at age 73, having been in politics for 40 years, I think there is some advantage to experience,” DeWine said. “I’m literally using my lifetime of experience in government. I’d rather have that experience than not have it.”

Then DeWine, who at his coronavirus briefings often talks about lessons learned from the 1918 flu pandemic, made a comment that suggested he’s wondering how history will remember him.

“Every governor who I talked to before I took the oath of office said, ‘There’ll be something that comes up — you don’t have a clue what it is, but there’ll be something that comes up. It'll be a flood or a tornado,’” DeWine said. “Well, this is the ultimate crisis, a once-in-a-century crisis. I kind of laughed with a friend last night. I said, ‘We haven't had this in 102 years, and I'm the governor when it happens.’ You can’t make this stuff up, right?”