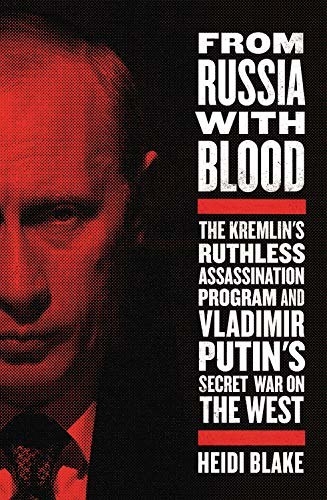

A new book by BuzzFeed News’s Global Investigations Editor connects 14 suspected Russian assassinations on British soil — first exposed by BuzzFeed News in 2017 — to a much wider campaign of Kremlin-sanctioned killing around the world. This exclusive excerpt of From Russia with Blood: The Kremlin's Ruthless Assassination Program and Vladimir Putin's Secret War on the West reveals Scotland Yard’s desperate scramble to shield the disorderly oligarch Boris Berezovsky from a string of audacious murder plots in the heart of London.

Rain was spreading like a fresh bruise across the London sky as the unmarked car rolled up Whitehall toward Big Ben. The Scotland Yard protection officer scanned the road with a well-trained eye, clocking potential hazards as the car passed the spiked iron gates of Downing Street, and swung right on Parliament Square. He had spent years guarding countless government ministers and visiting foreign dignitaries, and there wasn’t an inch of this maze of power that he didn’t know like the back of his hand.

Nothing looked amiss as the car sloshed to a stop outside a modern multicolored glass building. London’s black-cab drivers were doing roaring business in the rain, and the pavements were gray and empty except for a smattering of pedestrians under dripping umbrellas. But the city was in crisis. Days before, the FSB defector Alexander Litvinenko had died in the full glare of the world’s media after being poisoned with radioactive polonium. But first, he managed to solve his own murder by publicly accusing the Kremlin of orchestrating his killing in a statement issued from his deathbed. The protection officer had been summoned as the government scrambled to respond to this brazen nuclear attack in the heart of London.

The doors to the Home Office slid open and the officer strode into the command center of British state security. He was shown upstairs to a large boardroom where a host of grave-faced officials was waiting. A stale sort of mugginess in the air told him they had been cooped up together for some time.

“There were six people on the Kremlin’s hit list,” the woman at the head of the table said as soon as he sat, “and they have already killed Litvinenko.” Officials from MI5, MI6, and GCHQ were seated around the table, the officer noted, alongside the Home Office security chiefs. “This is a direct policy of the Russian state: they are killing dissidents,” the chair continued. “We have some here, and they are coming for them.” She addressed him directly. “Make them safe,” she commanded.

The exiled oligarch Boris Berezovsky and the Chechen rebel leader Akhmed Zakayev were judged to be under “severe” threat of assassination, the officials around the table explained, meaning an attack was considered “highly likely,” while a Russian journalist living in Britain and the Cold War defector Oleg Gordievsky had also been identified as Kremlin targets. Another political hit on British soil would be an “unimaginable” disaster for the government as it struggled to salvage relations with Moscow and restore public confidence in the wake of the Litvinenko imbroglio. So the Home Office wanted Scotland Yard’s Specialist Protection Command to work alongside the security services to provide “defense in depth” for each of the exiles on the Kremlin’s hit list.

Specialist Protection was usually tasked with guarding the prime minister and members of the cabinet, so its officers had the same level of security clearance as Scotland Yard’s counterterrorism command. That meant they could be briefed on intelligence British spies had gathered about the threats to the Russians on their watch.

Over the week that followed, they learned about the FSB’s poison factory outside Moscow, where armies of state scientists were developing an ever-expanding suite of chemical and biological weapons for use against individual targets. There were poisons designed to make death look natural by triggering fast-acting cancers, heart attacks, and other fatal illnesses. There were labs set up to study the biomolecular structure of prescription medicines and work out what could be added to turn a common cure into a deadly cocktail. And the state had developed a whole arsenal of psychotropic drugs to destabilize its enemies—powerful mood-altering substances designed to plunge targets into enough mental anguish to take their own lives or to make staged suicides look believable.

That Russia had poured such unimaginable resources into providing its hit squads with the tools of undetectable murder made the brazenness of Litvinenko’s killing even more perplexing. Polonium had the potential to be the perfect traceless poison: its alpha rays made it hard to detect, and with a smaller dose Litvinenko would probably have died quietly of cancer a few months later. Perhaps, the security officials thought, his two assassins had overdosed him accidentally in their desperation to get the job done. Or maybe his death was deliberately dramatic, designed to send a signal to Russia’s dissident diaspora in Britain. Either way, there was one thing the protection officer learned for sure: even if it looked like the death of a Russian exile was the result of natural causes, accident, or suicide, that conclusion might well not be worth the autopsy paper it was written on.

To add to the complexity, the FSB was inextricably intertwined with Russian mafia groups, which in turn had deep links to powerful organized crime gangs in Britain, so Scotland Yard needed to be ready for anything from a sophisticated chemical, biological, or nuclear attack to a crude hit contracted out to a London gangster for cash.

The greatest threat, by far, was to Berezovsky. The oligarch had made himself Russia’s public enemy number one through his relentless attacks on the Kremlin and his efforts to foment insurrection in Putin’s backyard, and he had effectively appointed himself the chef de mission of the entire dissident community in the UK. He had already survived several assassination attempts, and the Russia watchers were getting a steady stream of intelligence about new plots to kill him. Russia’s state security and organized crime complex had grown into a multiheaded hydra under Putin’s auspices, and competing factions within the FSB, the mafia, and the country’s military intelligence agency were all vying for the chance to harpoon the president’s white whale.

Shielding Berezovsky was now the protection officer’s top priority. It was time to pay a visit to Down Street.

Berezovsky was in typically rambunctious spirits. The murder of Litvinenko was a sickening blow, but it was also a resounding vindication. The assassination had, as the defector said in his dying statement, shown just how brutal Putin truly was, and finally the world was listening. His office on Down Street was abuzz as the oligarch and his acolytes made sense of what had happened and conspired to ram home the message of their friend’s murder.

For his own part, Berezovsky had no doubt about who had administered the polonium—but he was skeptical that Litvinenko was the intended target. Hadn’t Berezovsky himself been warned, years before, of a radioactive plot to kill him on British soil? Wasn’t he Putin’s true nemesis? The oligarch was busy telling everyone that the assassins had really been sent to eliminate him but must have failed and seized the chance to poison Litvinenko instead. So when the protection officer showed up in his office with the news that he was at the top of the Kremlin’s UK hit list, he was thrilled. Finally the state was endorsing what he had been saying all along: Vladimir Putin was trying to kill him.

The protection officer was a tall, elegant man with close-cropped silver hair and pale blue eyes. He was a shade more erudite than many of his Scotland Yard colleagues, and he formed an easy rapport with Berezovsky. It would be necessary, he explained, to scour every detail of the oligarch’s lifestyle for weak spots that could be exploited by the Kremlin’s assassins. The first step was to perform a full “ingestion audit”—cataloging everything Berezovsky consumed, to assess his susceptibility to poisoning. During a series of interviews, officers filled their notebooks with an exhaustive list of anything the oligarch ate and drank, learning more than they ever thought they would about the finest wines and whiskeys money could buy, as well as documenting all the creams and lotions he applied to his body and the medication he was taking. It did not take long to identify a major problem.

Berezovsky was heavily reliant on Viagra, and, worse, he was taking a penis-enlargement formula that he had specially shipped over from Moscow. Still more alarming was his appetite for teenage girls, which made him a sitting duck for honey traps. The oligarch was constantly being contacted by disturbingly young sex workers from the former USSR and he frequently ferried them over to Britain for sessions on his private plane.

I have the absurd responsibility of trying to persuade a sixty-year-old billionaire that he has to rein all this in, the protection officer reflected wearily as he reviewed the results of his lifestyle audit. But he was used to this sort of ethical dilemma from years of guarding the great and the good in London. When an ambassador did drugs in the back of the car, or a diplomat brought a hooker back to his hotel, it was part of the job to look away. “I’m not going to sit here giving you a lecture on morals or ethics, but you’re very vulnerable here,” was all he said to his charge. “This is how they’ll kill you.”

The problem wasn’t just the girls. Berezovsky was forever being approached over the transom by would-be business partners and political allies who wanted his funding for this new enterprise or that new opposition party, and he was all too free and easy about meeting anyone who asked to see him.

Then there was the challenge of separating the Kremlin-sanctioned threats from those arising from the oligarch’s own risky business dealings. Berezovsky had tangled often enough with organized crime to acquire some nasty private adversaries who had tried to take him out before, but the officer’s remit was limited to protecting him from government assassins. The problem was that Berezovsky’s private enemies could easily hire a moonlighting FSB hit squad to go after him, and the state was equally capable of enlisting another oligarch or mafia boss to orchestrate his killing as a cutout, so it was all but impossible to be sure where any given threat really originated.

The officer reasoned that there was no point confronting Berezovsky about the darker side of his life. After all, he would never answer truthfully anyway. But he instructed the oligarch not to meet anyone who approached him out of the blue on any pretext—be it sexual, commercial, or political—without first passing on the details to Scotland Yard for vetting.

The intelligence flowing into Specialist Protection from Britain’s spy agencies indicated an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of new threats against Berezovsky. The officers were deluged with the names and photographs of a rapidly changing cast of individuals linked to the Russian security services or organized crime who were believed to be involved in plans to kill the oligarch. When a fresh plot emerged, officers would track Berezovsky down and yank him out of whatever dinner or business meeting he was attending to warn him he was in imminent danger.

The protection officer began to feel he was living in a John le Carré novel, meeting Berezovsky furtively at night on misty street corners in Belgravia to show him mug shots of his latest would-be assassins under the lamplight and implore him, please, for God’s sake, not to agree to meet them.

The others on the Kremlin’s hit list had adapted well enough to their new security regimes. The rebel leader Zakayev accepted an armed guard at his house when the threat level was deemed high, and he never met anyone new without careful vetting and countersurveillance measures. Gordievsky and the Russian journalist were conscientious about their safety. But Berezovsky was impossibly unruly.

On more than one occasion, he called the protection officer to announce that he had just met someone he had been warned might be part of a plot to kill him. And he flatly refused to stop antagonizing the Kremlin. He kept traveling to Belarus and Georgia to stoke unrest right on Putin’s doorstep—even after being told that Scotland Yard could do nothing to protect him when he was overseas. And every time he gave another interview in which he took a potshot at Putin, fresh intelligence would flood in from Britain’s listening posts in Moscow indicating that new plans were being laid to silence him. It was almost, the protection officer thought, as if you could feel the chill wind blowing in from the east.

But the oligarch seemed to thrive on it. “I am what I am,” he would say. “I am Boris Berezovsky, and I crave conflict.” It was as if he had a strange sort of destructive energy, the officer thought, that made him want to run right into danger.

Though he had had stayed relatively quiet immediately after Litvinenko’s slaying, by the spring the oligarch was ready to launch his next broadside. The protection officer woke one day in April to discover that his charge had given an interview to the Guardian renewing his declaration that he was plotting the violent overthrow of President Putin. Berezovsky claimed he had forged close relationships with members of Russia’s ruling elite and was bankrolling secret plans to mount a palace coup. “We need to use force,” he told the newspaper. “It isn’t possible to change this regime through democratic means.”

The Kremlin immediately hit back, denouncing Berezovsky’s call for revolution as a criminal offense that should void his refugee status in Britain. Scotland Yard said it would investigate those allegations, but the oligarch was unconcerned: the courts had already ruled that he couldn’t be sent back to Russia to stand trial.

The protection officer was horrified. Berezovsky’s latest pronouncement was followed by yet another flood of intelligence indicating that the FSB was setting up a fresh plot to kill him. And this was no empty threat. Soon after the first reports came in, Specialist Protection received an urgent call: Word had just come over the wire that an assassin was on his way to Britain.

The hit man was a fearsome figure in the Russian ganglands—and he was no stranger to the man he was coming to kill. Movladi Atlangeriev was the godfather of Moscow’s Chechen mafia, known as Lord or, more reverently, Lenin throughout the underworld. He started out in the ’70s as a smart young Chechen hoodlum with a taste for fast Western cars and a talent for burglary and rose to riches in the ’80s running a gang of thieves targeting wealthy students across the capital. At the turn of the decade, as communism fell, he persuaded the heads of the city’s most prosperous Chechen crime groups to band together and form a single supersyndicate under his leadership—and that was how he became one of the most powerful gang bosses in Moscow.

The new group was called the Lozanskaya, and it soon asserted its strength in a series of bloody skirmishes with the local mob, leaving the streets strewn with the mutilated bodies of rival gang bosses. Racketeering, extortion, robbery, and contract killings were its stock-in-trade. But Atlangeriev was a suave man with smoky good looks and an enterprising mind to match his wardrobe of well-cut suits, and he blended well with Russia’s emerging business elite. The gang quickly branched out under his command, taking over swaths of the city’s gas stations and car showrooms. That was how it established a lucrative relationship with Berezovsky.

The businessman made good money selling Ladas through dealerships under the gang’s control, and then he paid the Lozanskaya to provide protection as his car businesses grew rapidly in the early ’90s. When Berezovsky was attacked with a car bomb during a battle with the gang boss Sergei “Sylvester” Timofeev, some said it was Atlangeriev’s mob who had struck violently back on his behalf. And when the oligarch fell out of favor with Putin and fled to Britain, the Chechen crime lord kept in touch.

Now, in June of 2007, Atlangeriev was on his way to London, and the Russia watchers knew he was coming with orders to kill Berezovsky. The intelligence pointing to his involvement in a live FSB plot to eliminate the oligarch had come through six weeks earlier, and the protection officer had been dispatched to instruct Berezovsky not to meet him under any circumstances.

Atlangeriev’s movements and communications were monitored, and when he bought flights to London via Vienna, the protection officer received an urgent call from MI5. “He’s arriving at Heathrow,” the voice at the other end of the phone said. “Remove the target.”

The officer raced over to Down Street to tell Berezovsky his assassin was on the way and he needed to get out of the country immediately. As always, the oligarch perked up at the prospect of an adventure and flung open his office door with a flourish. “Warm up the aircraft!” he bellowed across the lobby to his secretary. “I need to leave today.”

Berezovsky took off for Israel, accompanied by a young officer who had just joined Specialist Protection after a spell as a London beat cop and couldn’t believe that this was his new world. The private jet landed at Ben Gurion Airport, and the party crossed the tarmac to a helicopter waiting to whisk them out to the coastal town of Eilat, where the oligarch’s £200 million superyacht rose like a gleaming shark’s fin from the turquoise waters of the Red Sea.

The rookie officer was shown aboard by an Amazonian hostess who took him to a private cabin, where a dinner suit was laid out on the bed in his exact size. There were deck clothes, too—shorts, sandals, polo shirts, shoes, and a cap—all branded with the yacht’s name, Thunder B. The vessel had an onboard wardrobe department with clothes in every measurement so the oligarch could keep his guests appropriately dressed whatever the weather. The young cop looked around him in disbelief and decided that if he was doing this, he might as well do it properly. He donned the dinner jacket and bow tie and made his way up on deck.

Back in London, Scotland Yard’s counterterrorism department had swung into high gear alongside the Specialist Protection unit to prepare a response plan for the assassin’s arrival. Now that the target was secure, Scotland Yard could afford to play cat and mouse with the assassin. Officers formed a “pursue and attack” plan: Surveillance teams would follow Atlangeriev around London for as long as possible in order to gather intelligence about his activities before swooping in and arresting him when it looked like he was ready to strike.

The hit man was not coming alone: He was traveling with a young boy, which looked like the same modus operandi one of Litvinenko’s assassins had employed in bringing his family to London as a cover for the hit. Maybe, the officers hoped, if they stayed on his tail long enough the new assassin might even lead them to a secret polonium warehouse in the heart of the city.

“I need pursuit teams. Gunships. Three surveillance teams—sixty officers on the ground,” the protection officer told Scotland Yard’s counterterrorism commander. “We need chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear teams in full protective gear sent in to swab all his luggage.”

The police chiefs agreed on the strategy—but then they were summoned to the Cabinet Office, where a meeting had been convened to brief ministers and officials from the Home Office, Foreign Office, and Downing Street. By then, Atlangeriev was in the air and time was short, but the officers met with resistance as they laid out their plan. If Scotland Yard got caught tailing an FSB agent around London, there would be a major public fuss. The diplomatic fallout with Russia would be another headache the government didn’t need. Couldn’t the hit man just be detained at the border? The officers pointed out that Atlangeriev hadn’t yet committed any arrestable offenses in Britain, and the intelligence implicating him in a murder plot couldn’t be revealed without exposing sensitive sources and listening posts in Moscow. It was essential to follow him in order to prove he really was here to kill Berezovsky before they could arrest him.

After some wrangling, the operation was approved—but the officers were instructed not to say a word to the media either before or afterward. If they were successful in apprehending Atlangeriev and journalists called with questions, their statement should be as short and uninformative as possible. “Police have arrested someone. End.” Berezovsky’s threat level was moved from “severe” to “critical”—meaning an attack was considered imminent.

Atlangeriev would arrive in just a few hours. An operations room was hastily set up, where commanding officers could coordinate the activities of surveillance teams on the ground, with hazardous materials units sweeping behind the assassin for radiation traces and armed response teams at the ready.

In a nearby room was a cabal of security-cleared officers tasked with monitoring a live intelligence feed from MI5 and MI6 as well as reading Atlangeriev’s text messages and listening to his phone calls in real time as soon as he landed. That classified information and intercepted material had to be kept out of the central evidence chain, otherwise it would have to be disclosed in court if Atlangeriev ever came to trial, which would reveal sensitive sources and methods. But when the officers in the intel cell picked up anything relevant, they were to bring it into the ops room and read it out to the senior commanding officer.

Once the ops room and the intel cell were up and running, the surveillance teams were stationed around the airport, and the hazmat crews donned their protective gear. It was time for police chiefs to contact bosses at Heathrow to prepare the ground for the assassin’s arrival.

The plane on which Atlangeriev landed was held on the airstrip for a little longer than usual. The hit man waited with the other passengers, unaware that his bag had been removed from the hold and was being searched and swabbed by officers in hazmat suits outside. When the passengers were allowed to disembark, Atlangeriev and his child accomplice breezed through passport control, collected their luggage from the carousel, and cleared customs with nothing to declare. The pair made their way out of the terminal building and approached the cab stand, where a black taxi was waiting. They climbed in.

London’s iconic black cabs had long been the protection officer’s secret weapon. Unbeknownst to most Londoners, Scotland Yard owned a secret squadron of such cabs for use in special operations, and the security and intelligence services also ran their own fleets of undercover taxis. The cars were so ubiquitous as to be invisible, so there was no more anonymous way to travel around the city. The protection officer had used them to move Tony Blair during an active assassination plot and to transport the British-Indian novelist Salman Rushdie around London during his decade in hiding following the publication of The Satanic Verses. It was possible to make anyone, no matter how high-profile, disappear inside the passenger compartment of a black cab—and a well-timed taxi ride was often the best way to get up close and personal with a surveillance target.

Atlangeriev directed his taxi driver to the Hilton on Park Lane and settled back in the leather seat, unaware that he had just revealed where he was staying to the officers tracking his every move at Scotland Yard. The driver dropped the hit man and his young accomplice outside the hotel, and the pair made their way through the revolving doors at the base of the glowing blue skyscraper. Then officers from the intel cell came running into the ops room. Atlangeriev had placed a call to Berezovsky.

By the time his phone rang on board Thunder B, the oligarch was well prepared. The morning after his hasty escape from Britain, three British security officers had arrived in Eilat and boarded the yacht to brief him. It was a baking hot day, and the officers looked disheveled in sweat-dampened shorts and T-shirts, but they waved away Berezovsky’s largesse and made it clear they were there on serious business. Gathered around a table in the shade on the lower outside deck, they told him they needed his help to buy Scotland Yard some time. If Atlangeriev realized that Berezovsky was completely out of reach, he might just abort the mission and go back to Russia before the authorities had a chance to gather any intelligence. So when the would-be assassin called, they told him to act friendly and say he’d be available to meet in a few days’ time.

Berezovsky wasn’t ordinarily one to follow instructions, but he was relishing his leading role at the center of this live operation against an enemy agent, so he did as he was told when Atlangeriev called. Then he phoned Down Street and told his secretaries to be on high alert for the assassin’s arrival and to tell anyone who called that he was busy. After that, all that remained was to wait. He passed an enjoyable few days on board Thunder B, sunning himself on deck, scuba diving, and zooming around on his Jet Ski while the British authorities tracked his assassin around London.

Scotland Yard’s surveillance operatives found themselves on an unexpected sightseeing tour. They had hoped Atlangeriev might lead them to the heart of FSB activity in the capital, or possibly to a warehouse crammed with radiological weapons, but ever since his call to Berezovsky, the hit man had acted for all the world like a tourist showing a kid around the city. As he and his young companion traipsed through Trafalgar Square and past Buckingham Palace, the hazardous materials officers crept behind them swabbing and scanning for traces of toxins or radiation—but everything came up clean.

The officers judged that when Atlangeriev separated from the boy, that would be the indicator that he was gearing up to strike. They waited, but the sightseeing went on for days, and the protection officer began to get twitchy. Berezovsky was a busy man: he couldn’t stay on his yacht forever. Then finally word came back from the surveillance team that the hit man had set out from the Hilton alone.

“This is the critical moment,” the commanding officer shouted. Atlangeriev had dropped his easy touristic demeanor, and now he was visibly wary of being tailed. He performed textbook countersurveillance moves as he navigated the city—taking circuitous routes, doubling back on himself, and hopping on and off different modes of transportation to throw off anyone trying to follow. Between them, the surveillance teams just about managed to stay on his tail as he visited various addresses—but they couldn’t follow him inside without blowing their cover. Then a readout from the intel cell suggested that the hit man was planning to buy a gun.

“We need to take him off the board,” the commanding officer told the team. Scotland Yard called the officers guarding Berezovsky on Thunder B and told them to prepare him for his big moment. It was time to call his would-be assassin and propose a meeting.

That evening, three plainclothes police officers positioned themselves in the lobby at Down Street. The receptionists on the second floor had been asked to stay late to greet the assassin politely when he turned up, and they waited with trepidation as time ticked by without anyone appearing. After a while, they called downstairs to ask the elderly concierge at the front desk whether anyone had arrived to see Mr. Berezovsky. Yes, the old man said a little shakily, a gentleman had come in a few moments ago, and now there were three others with him in the lobby.

“What are the gentlemen doing now?” the receptionist asked. “The gentlemen are talking,” the concierge replied. “Three of them are lying down, and one is standing.”

When Atlangeriev entered the lobby, two of the officers had swooped in and pinned him to the floor before he reached the elevator, while the third flashed the concierge his police badge. The hit man was arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to murder and taken into police custody, where he was interrogated for two days, while his child accomplice was taken into the care of social services.

But then the order came down to let him go without charge. It wouldn’t be possible to make charges stick without disclosing intelligence that would give away far too much about British sources in Moscow, the officers were told, and the diplomatic fallout from publicly accusing the Kremlin of ordering another assassination in Britain so soon after Litvinenko’s would have been catastrophic. So Atlangeriev was handed over to immigration officials who designated him a “persona non grata” and put him on a plane back to Russia. That, the officers were assured by their superiors, amounted to a “really strong diplomatic poke in the eye.”

There was a commotion in some quarters at Scotland Yard over the decision to send the assassin home, but others were more sanguine. The protection officer comforted himself with the thought that the FSB might have killed one exile on British soil, but now Scotland Yard had prevented the murder of another. The way he looked at it, that evened the score. He called Berezovsky and told him it was safe to come home.

By then journalists had gotten wind of the dramatic arrest in Mayfair and were inundating Scotland Yard with questions. The press bureau gave out the elliptical response the government had preordained, and when his jet landed, Berezovsky was told to say nothing. The one thing that would increase the threat to his life, he was told, would be to embarrass Russia over its failure to kill him. “Just lie low and keep your head down,” the protection officer said sternly.

Soon after, Berezovsky stood up in front of a packed press conference in central London and told journalists that Scotland Yard had just foiled a Kremlin plot to assassinate him. “I think the same people behind this plot were behind the plot against Alexander Litvinenko,” he said. “Not only people in general, but Putin personally.”

Berezovsky held back the details of who had come for him and how the plot had been stopped, but he told his friends he had to go public with the attempt on his life in order to protect himself. Keeping state secrets was a dangerous game, he said: it was safest that the whole world know the truth. And, of course, he had never been one to pass up the chance for a dramatic press conference.

The protection officer was furious. “We’ve been fucked up the arse,” he shouted at the MI5 liaison officer in charge of monitoring threats against Berezovsky. He couldn’t shake the notion that he and his colleagues had unwittingly become pawns in Berezovsky’s big game.

Six months after the press conference, Scotland Yard received a report of the fate that had awaited Atlangeriev upon his return to Moscow. As he walked out of a traditional city-center restaurant on a bitterly cold winter night, the crime lord had been assailed by two men and bundled into the back of a car, which sped off into the darkness. Berezovsky’s failed assassin had been driven out into the woods and shot at point-blank range in the head. ●

Adapted from From Russia with Blood: The Kremlin's Ruthless Assassination Program and Vladimir Putin's Secret War on the West, published by Mulholland Books, an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of the Hachette Book Group. Copyright © 2019 by Heidi Blake.