Last week, the US launched a military strike against the Syrian government in response to its use of chemical weapons.

What's less than clear now, though, is what rises to the level of a US response these days.

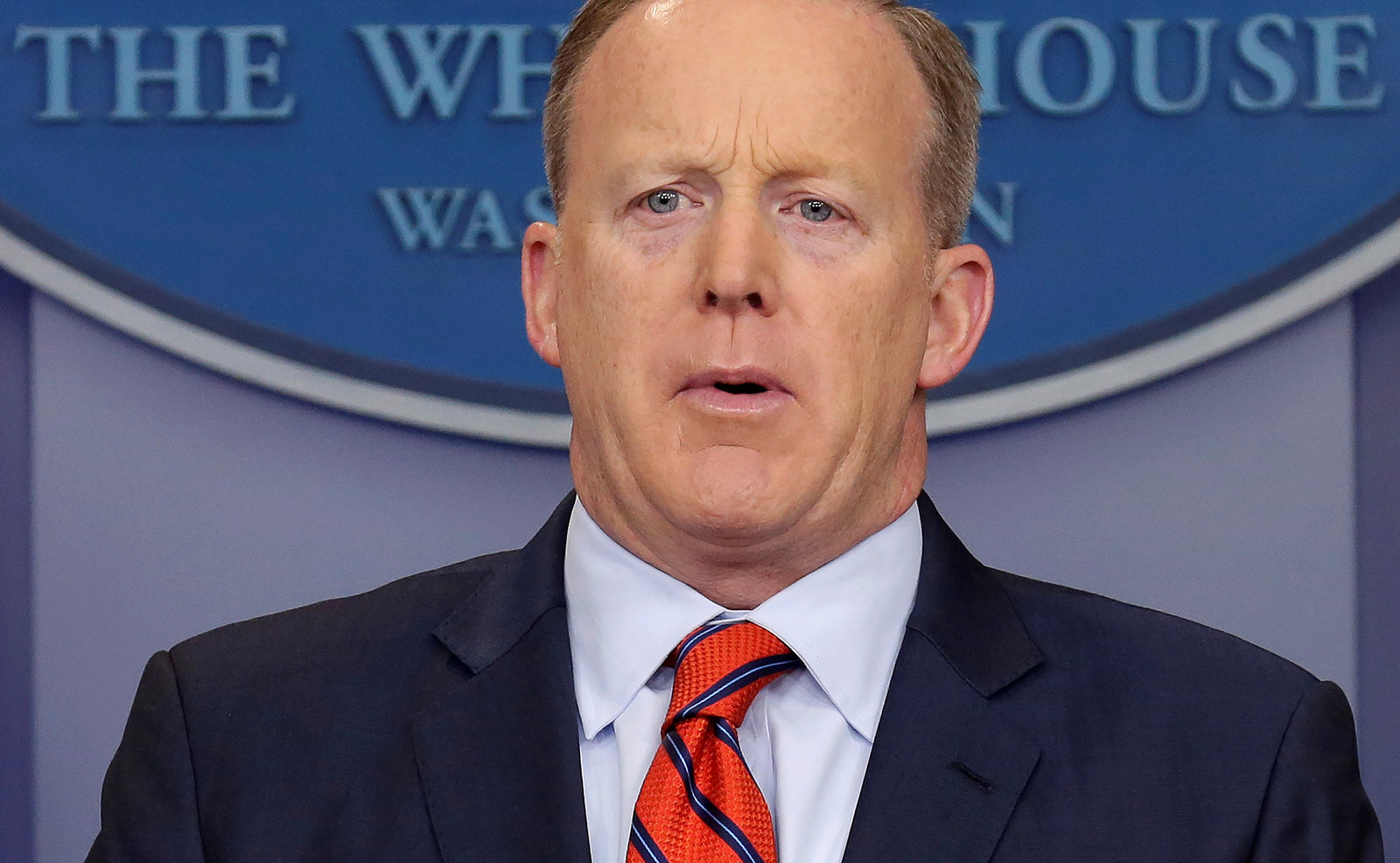

Press Sec. on Syria, citing gas and barrel bombs: "If we see this kind of action again, we hold open the possibilit… https://t.co/SPWVhxqnD2

White House press secretary Sean Spicer on Monday wouldn't go into details, saying, "If we see this kind of action again, we hold open the possibility of future action."

Meanwhile, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said in a statement that Trump "directed this action to deter future use of chemical weapons" and that Syria should know that it "would be ill-advised ever again to use chemical weapons."

At least part of the reason it's hard to nail down what would draw another US strike right now is because of Obama's "red line" moment back in 2012.

In its bid to show Trump as decisive, the administration justified the airstrikes by making it all about international law — which isn't what you'd expect from a White House that's made "America First" the basis of foreign policy.

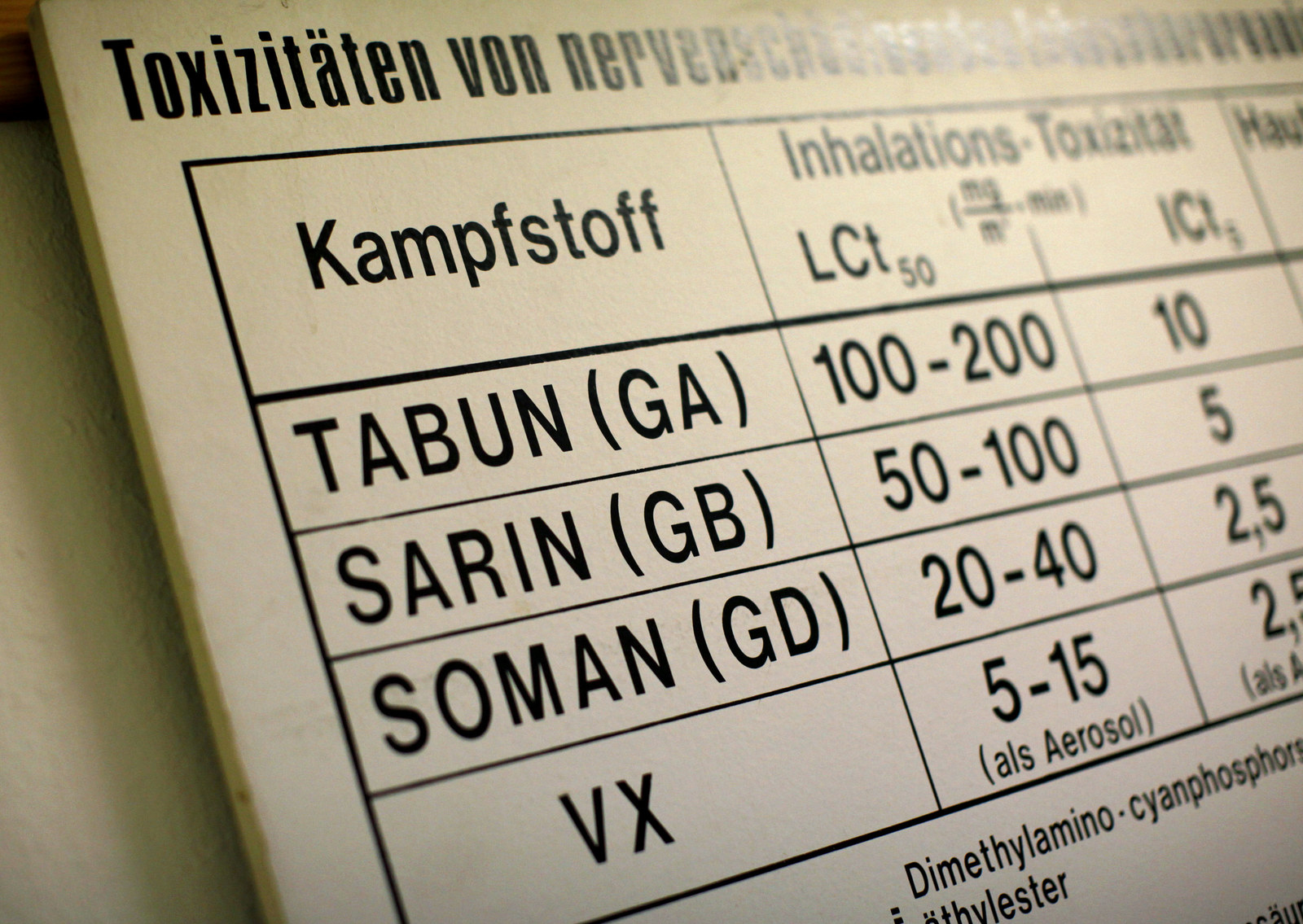

The global law surrounding the use of chemical weapons goes back to just after World War I, when the use of mustard gas and other chemicals in warfare first became possible.

Decades later, the ownership loophole would be closed with the ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which outright banned having them.

Since then, an estimated 90% of the declared banned chemical agents have been destroyed worldwide. But the "declared" part is important — the OPCW can only get rid of stockpiles it's aware of.

So what, then, is it about chemical weapons that makes them so dangerous that the US decided to bomb Syria for using them?

Strategically speaking? Not too much. No war has ever been won because the other side owned or was willing to use chemical weapons.

Spicer on Tuesday tried to compare Assad's use of sarin to that of the Nazis, whose scientists had invented it as a pesticide in 1939. (They never used the lethal gas to attack Allied forces during the war.)

What chemical weapons are very good at is being used as a way to kill and terrorize civilians. Iraq's Kurdish population learned that first-hand during the late 1980s.

Toxic weapons have also been used by non-state actors, like the Japanese doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo, which unleashed sarin gas in a Tokyo subway in 1994, killing a dozen people.

Which brings us back to the 2013 deal to get the chemical weapons out of Syria, a task given to the UN and OPCW.

Since then, Syria has continued to launch chemical attacks, but not with banned chemicals. Instead, the regime has turned to chlorine attacks delivered via what are called barrel bombs.

Which returns us to Spicer's comments on Monday, which were very, very vague about what would actually draw more missiles from the US — which is a problem, by the administration's own standards.